Behind the ‘Iron Curtain’ of art’s greatest illustrator

As the NSW Art Gallery prepares to unveil the largest collection of Alphonse Mucha’s work seen in Australia, we delve into the illustrations that created a blueprint for modern poster art, hidden in the wake of Nazi Occupation and Communist rule.

When single-name celebrities spring to mind, typically they assume the form of a mid-80s popstar: Cher. Prince. Madonna.

But a 19th/20th century graphic artist – a minority outcast in the Austro-Hungarian regime whose friendship circle boasted a young Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin and Sarah Bernhardt, French cinema’s answer to Taylor Swift – crafted some of the most instantly recognisable works in European art.

Mucha, one of the chief architects of the art nouveau movement, remains one of most important artists to come out of the country now known as Czechia.

The career of the artist – whose full name was Alphonse Mucha – will be celebrated in an upcoming survey at the Art Gallery of NSW. The exhibition, opening this week, will be the most comprehensive showing of his work in Australia. The retrospective will canvass his oeuvre, which blurred the lines between commercial and fine art and which culminated in the career-defining masterpiece and ode to Slavic independence, The Slav Epic.

The first thing one notices with one of Mucha’s works is its familiarity. His name however, once of recognisable status on par with Beyonce, all but vanished from public consciousness.

The distinct calligraphic style woven with mythical imagery, has been the source of inspiration for musicians and designers alike, notably inspiring Pink Floyd’s Marquee ‘66 poster. Panels of illustrations depicting innocent floral motifs against seductive portrayals of women with undertones of life, death and freedom evoke the sentiment that carried Mucha’s career: “never to destroy, always to create.”

“Alphonse fell off the radar of traditional Western art historians,” explains his great-grandson Marcus Mucha, executive director of the Mucha Foundation.

Speaking from his home in Prague, the former Hollywood film producer details the process of unearthing hundreds of his ancestor’s works, “locked away behind the Iron Curtain” in an effort to protect the precious pieces from Nazi Occupation and ensuing Communist rule.

Reflecting on his great-grandfather’s legacy, it appears a modern story of Mucha’s life and expansive career can begin with his death – with harrowing parallels viscerally relevant to today’s political climate.

Among one of the first people arrested by the Gestapo, Mucha’s idea of Czech nationalism, paired with his Freemason affiliations, posed a direct threat to Hitler’s despotic vision of Europe at the height of Nazi Germany’s powers. Isolated for 10 days of interrogation, the artist – then in his 70s – was eventually let go due to his ailing health. A case of pneumonia contracted during incarceration would eventually lead to his death less than four months later. He was 78.

The portrait Marcus paints of his great-grandfather’s funeral is evocative of the decadent works he left behind: the streets of Prague swarmed with more than 100,000 Czechs bidding farewell to an artist and pseudo national hero.

The city, overrun by Nazis, echoed with cries for freedom and peace. It was a stark soundtrack to the dark days of invasion ahead.

“It’s very powerful,” Marcus muses.

“He saw the world leading to utopian-like peace, where countries grand and small could coexist. He thought that the end of WWI would achieve that – but I think his philosophy is still relevant in a world that is more complex than any other I can remember in my lifetime.”

The upcoming exhibit, created in close co-operation with the Mucha Foundation, seeks to draw on the artist’s enduring commitment to peace. Marcus suggests prior shows have coincidentally reflected harrowing parallels between themes the artist explored and current events.

In a grand display of his work at the Czech Senate in 2022, curator of the Mucha Foundation Tomoko Sato selected an illustration of a Slavic peasant woman cradling a dying baby.

“We had prepared for weeks ahead of the show, with Tomoko specifically picking that one image to be front and centre,” Marcus says.

“A month before we opened, the tanks rolled into Ukraine. The impact was chilling.”

The work, Study for Russia Restituenda, crafted during the Russian Civil War, was a plea to help starving children. Such a compassionate image, adapted from Christian iconography of Mother and Child, leveraged Latin – then a universal language – to communicate the impartiality of the humanitarian effort. “Russia Must Recover” was its message.

“It is just as relevant now as it was back then,” Marcus says.

Such a humanist philosophy drove Mucha’s career over five decades. His works included posters, illustrations, jewellery and photography that blurred the line between fine and contemporary art. The artist, Marcus says, democratised access to his works through commercial practices and sprawling displays of historic nationalism, made accessible to the public.

The ANSW exhibit’s senior curator Jackie Dunn says the logistics of the 200-work spectacle were daunting. She points to The Slav Epic – Mucha’s greatest work both in artistic prowess, meaning and size. It is a mammoth love letter to Slavic unity, depicting an episodic account of history and culture sprawled out over 20 floor-to-ceiling canvases. The painting cycle took the artist 18 years to complete.

Dunn says it is a key work in a show that will appeal to a modern audience. Poring over every detail, she says the gallery fixated on determining whether it boasted “overly nationalistic sentiments”. “After dealing with the events of WWI his concern as he moves towards the period of destabilisation – before WWII – is just of universal peace, and as he puts it in beautiful old school terms, ‘universal brotherhood’,” she explains.

“And it’s interesting for us to think, why has that become a problematic idea? This is a figure who just wanted unity around the world,” she adds, touching on the spiritualist drive for Mucha’s roots and culture that dictated the majority of his later life’s work.

The 6x4m skins are too fragile to move and so will not be on display physically at AGNSW. Instead, Dunn says the works have been digitised and reimagined as an interactive projection.

Born a poverty-stricken outcast in 1860 in Ivancice, near the southern Moravian city of Brno, Mucha grew notoriously frustrated by his own ascent. A humble art student sponsored to pursue his craft in Munich, then Paris, he skyrocketed to success with a single work tipped as the creation of the “new woman”.

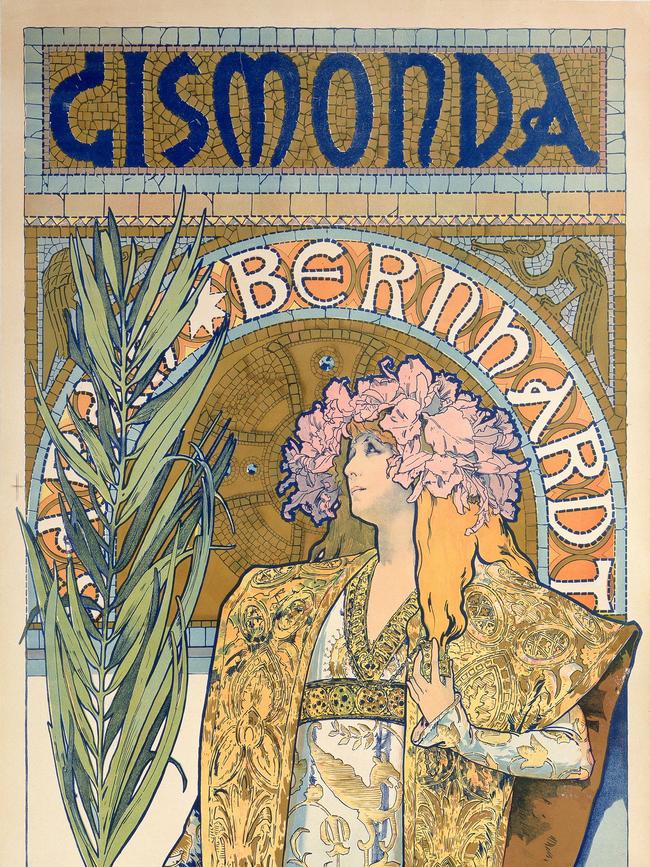

Dubbed an antidote to a rigid, masculine world, his divine elevation of the female form epitomised through his 1894 theatre poster for Gismonda, starring powerhouse French actor Sarah Bernhardt, lit up the art landscape with a palette of muted pastels, botanical backdrops and a democratised approach to the fine craft.

Upon the work’s release, the Czech artist’s radically stylised works, swiftly dubbed Le Style Mucha, were ravenously ripped from the streets and collected by fans.

His celebrity status saw him tour across Europe and the US, and eventually saw him attributed as the originator of display advertising, now synonymous with legacy brands Ruinart Champagne, Nestle and Moet-Chandon.

“It’s that sense of legacy – that’s what we capture in the final part of the show, where you see just how much art has paid homage to the style and philosophy Mucha created,” Dunn says.

“He had this capacity to create a brand identity that without even describing his message or naming a product, he could extraordinarily convey a message that touched people around the world.”

Marcus reflects on the process of chronicling a relative’s extravagant artistic legacy for the Sydney exhibition. In unearthing the works, he discovered the private thoughts of a world-famous artist who was uncharacteristically a man of few words.

“There was one anecdote where he wrote about sleepless nights while he was working in Paris with Paul Gauguin,” he says. “He wrote that this very crazy red-headed man came home with him one night and kept them up to all hours – we checked with our friends at the van Gogh Museum and they confirmed it was the time he (Vincent van Gogh) was in Paris, too!”

The artist, decorated and decorative, was bound by the ideology that access to beautiful images and motifs promoted a better world. It’s that notion that will be celebrated in the Sydney show, says Dunn, who also promises some glittering surprises for attendees to be found in the artist’s collection of jewellery design.

“He was a 16-hour a day worker, and he had this kind of belief that if an artist had any talent they should get on with it and give it to the world,” Dunn says.

“The body and volume of work he put out at various parts of his life is truly remarkable.”

Alphonse Mucha: Spirit of Art Nouveau is on now at the Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney, until September 22. The exhibition coincides with the annual Archibald, Wynne and Sulman prizes exhibition.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout