Bay watch puts Melbourne in a new nautical perspective

THE Sea of Dreams exhibition should cause viewers to reassess Melbourne as a city built on the sea.

THE topography of a city has an indisputable, though imponderable relation to its character and that of its inhabitants: the hills of Sydney, for example, and the flatness of Melbourne seem somehow emblematic of the very different mood and sensibility of the two cities.

Sydney is full of breaks and interruptions and transitions between quarters of the city, largely based on the succession of high and low ground, the alternation of open views and enclosed hollows, of eastern and western slopes, of good and bad aspects.

Melbourne, on the contrary, is almost completely flat. This has allowed the city to be laid out in a vast grid of primary and secondary streets with a network of alleyways, a far more rational organisation than Sydney, which is squeezed into a relatively exiguous area between natural boundaries.

Everything seems more spacious in Melbourne - visitors to both cities will have noticed that cafes in Melbourne are large and comfortable whereas in Sydney a cafe can hardly be considered chic if it has more than half a dozen tables and preferably some hard little stools or even milk crates on the footpath.

But the most distinctive and intriguing thing about Melbourne, especially from the perspective of a Sydneysider, is the lack of any boundary between different quarters. If you go for a walk through the long grid streets of Melbourne, whether through commercial or residential areas, you will pass insensibly from wealthy to poorer sections, from well-maintained houses with cared-for gardens to rundown places with gardens that have gone to seed, or from busy and lively shopping streets to seedy stretches with empty windows - and then a little further on, back again to prosperity.

One gets the impression of a city that is more discreet and private than Sydney, where differences are more nuanced and perhaps also more fluid. The rich don't have better views, since there are no views to speak of; they simply have bigger and more elegant residences. The differences are inside rather than outside. And all of this suggests, at least to the flaneur who has nothing to do but ponder the mood of the city he is walking through, the conditions for a greater inner life than one expects in extroverted Sydney.

Of course the hilliness and flatness are indissociable from the most conspicuous difference between the respective topographies of the two places: Melbourne is a river city, while Sydney is built around a harbour. Or at least that is the impression one has of Melbourne until one sees the city from the air, and then it is surprising to find how close to the sea it really is. But what is undeniable is that the sea has, for all its proximity, virtually no presence in the shape of Melbourne, while it is ubiquitous in Sydney and determines the morphology of the whole inner city and many of the suburban areas.

Nonetheless, Melbourne is indeed built on the sea, or rather in the enormous bay of Port Phillip, and it is the purpose of Sea of Dreams, at the Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery, to rediscover this fact and almost to propose a different way of thinking about the city and its environment. Perhaps the first part of the task is to constitute Port Phillip itself as a single object of the imagination, for it is so vast that we tend to think of its parts - such as Geelong or the Mornington Peninsula - as different and separate entities, when in fact they are part of the same geography, and of course part of a common history as well.

Sea of Dreams, curated by Jane Alexander, who is the director of the MPRG, began as a relatively simple idea, to document the bay through its representation by artists over the past couple of centuries. It soon became apparent, however, that there was an overwhelming amount of material available, and of outstanding historical interest. So the present show covers the period 1830-1914, and a second instalment in a couple of years' time will deal with the sequel from 1914 to the present.

The exhibition opens with a work that fittingly evokes its subject and several of its themes: James Howe Carse's 1871 painting of Dromana emphasises what must always have been the town's distinctive feature, an extremely long pier - much longer than it is today - stretching out into the comparatively shallow bay to where the water was deep enough to provide anchorage for large ocean-going vessels. The picture conveys something of the size of the bay itself, as well as the modest dimensions of the colonial settlement, perched on the shore and apparently then accessible only by water. Work and leisure are juxtaposed in the sailing boat and the tug in the foreground; and when we look closely at the tug and the crowd on the end of the pier, we realise that the subject of the picture is a farewell.

The exhibition, after this prelude, is divided into several sections which are at once thematic and roughly chronological, and which run from migrant beginnings to the popularisation of beachside leisure in the Edwardian period. In the earliest works, it is the experience of migration that is evoked, with its mixture of hope and sadness at separation from those left behind; those who set off as permanent migrants might never see their friends and relatives again, but there were also others who travelled to Australia to make their fortune, leaving behind wives and children with promises of returning rich.

Particularly interesting is a section dealing with life on shipboard, which, especially in the early years, was often extremely uncomfortable and even dangerous. Epidemics were particularly terrifying, but there was also the constant risk of shipwreck, especially in the approaches to Port Phillip Bay - the region became known as the Shipwreck Coast - and at the entrance through a narrow navigable channel.

The peril is vividly captured in an anonymous oil painting of a lifeboat labouring through choppy waters to rescue survivors of the wrecked Asa Packer in 1861.

Shipwrecks recur in later works from Frederick Horatio Bruford's Wreck of the Loch Ard (1878) to a beautiful little painting by Charles Conder, rarely seen because it belongs to a private collection, Wreck (1889).

The exhibition includes several pictures of the great clipper ships that made the voyage out from England both faster and more comfortable in the mid-century. There is a painting by Francis Hustwick of the Great Britain, one of the few vessels of the time that has survived; it can be visited today, in its restored state, in Bristol. Thomas Robertson's painting of The Red Jacket in Hobson's Bay (1856-57) depicts three of the fastest ships of the time at anchor together. One of these, however, the Lightning, met an unhappy end when a fire broke out in the hold and it was completely destroyed at anchor in Corio Bay at Geelong in 1869; the disaster is recorded in a contemporary print.

Thomas Robertson, who was a Scottish sea captain as well as a fine marine painter, is also represented by another impressive picture, simply titled Hobson's Bay (1860). The ship at anchor dominating the composition is the Victoria, a sail and steam naval vessel commissioned and financed by the still young colony to protect itself against possible attack.

The defence of the bay is another important theme, and there are images of fortifications and their artillery as well as other initiatives, such as the Cerberus, an iron-clad ship designed to carry heavy canons and to move around the bay like a floating citadel.

In spite of such serious concerns, leisure was also an important theme from an early period, as attested by Thomas Clark's Kenney's Baths, St Kilda (1854). Clark is better known as a high colonial landscape painter who later taught at the National Gallery School.

The marine subject, unusual for him, shows a decommissioned Swedish whaler that had been purchased by Captain Kenney, moored and sunk to the sea bed, filling the hold with water and making an indoor bathing establishment at a time when outdoor bathing was prohibited in daylight hours. This ship was for male customers only, but the enterprising captain soon set up another one for women bathers.

Another small and contemporary picture, by F.W. Wilson, shows the paddlesteamer Gondola on the Yarra in 1855; this little craft took ladies and gentlemen from the Prince's Bridge to Richmond, where its enterprising owner had established a pleasure resort called Cremorne Gardens. Apparently there was too much pleasure to be had there - whether amateur or professional - for the taste of the disapproving civic authorities, and the Gardens were closed down.

Parts of the bay became fashionable as places where the wealthy citizens of Melbourne either had coastal retreats or went on holiday excursions. One of the themes of the later part of the exhibition is the gradual democratisation of these originally relatively exclusive resorts as more numerous and inexpensive ferry services made them accessible to a broad public.

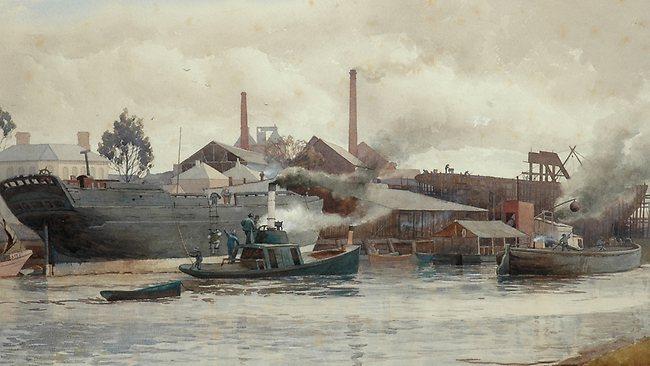

This is the period of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, in which artists represent both the working harboursides - as in John Mather's very fine watercolour Tug Boat (1886), or Ugo Catani's Queen's Wharf (1887) - and the wharves and ferries and beaches associated with holidays and leisure, as in several little pictures by Ambrose Patterson or Harold Septimus Power's Ozone, approaching the wharf, Dromana (1899), in which the crowd presumably of day-trippers is waiting to be picked up for their return home in the evening.

Among the best pictures in the later section are Tom Roberts's Slumbering sea, Mentone (1887) and two little sketches by Conder, Rickett's Point, Beaumaris (1890) and Centennial Choir at Sorrento (1888). Both of Conder's pictures are full of tiny thumbnail figures, all caught in characteristic attitudes and gestures that evoked a beachside life that did not yet involve public bathing - Roberts's The Sunny South (1887), not included in the exhibition, shows three young men bathing naked but in a secluded spot far from respectable eyes.

Paddling of course, was a permissible activity, as we see in Rickett's Point - and another picture not included, Conder's much bigger painting Holiday at Mentone (1888), shows a gentlemen sunbathing rather incongruously in a suit. Roberts's Slumbering sea is about another seaside pleasure, boating; in the very centre of the composition a young woman leans forward to steady the prow of a dinghy as it comes to shore.

The sea is still and glassy, for this body of water, which the exhibition allows us to consider, perhaps for the first time, as a single imaginative place, is as enclosed and protected as a lake: another metaphor, perhaps, for the sensibility of Melbourne.

Sea of dreams

Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery

to February 19