Bartlett Sher's production keeps South Pacific younger than springtime

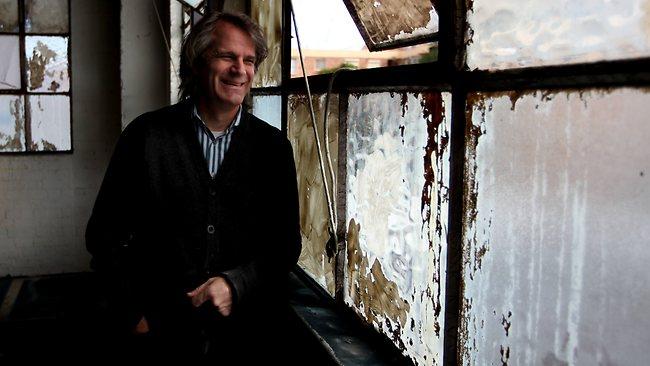

DIRECTOR Bartlett Sher finds plenty of contemporary resonances in South Pacific.

THE songs are famous. Even people who say they can't stand musicals will be able to hum them.

They may even find their hands rising to their heads and their hips swaying a little at the mere mention of that catchy tune, I'm Gonna Wash that Man Right Out of My Hair. They may go all suave and smoking jackety at the thought of Some Enchanted Evening.

What's especially fascinating about these songs, however, is that they remain in the zeitgeist even though the legendary musical they come from, Rodgers and Hammerstein's South Pacific, has not been performed on Broadway since its smash-hit prize-winning five-year run from 1949. People fresh from the experience of World War II were electrified. Time, however, softened its impact.

"It was a hugely popular musical, always. But it was a cheesy musical," Bartlett Sher is saying. His rangy body is slumped on a sofa and he's chewing through a sandwich on his lunch break from rehearsing the show at Opera Australia's Sydney headquarters. The 1958 film didn't help, he says, because it's "kind of not great ... And then the performance traditions got more and more naff and silly, like flag-waving and straw-chewing. And I think it got removed and remote, so no one really knew what to do with it."

South Pacific traces a short period in the history of Americans fighting the Japanese in the Pacific. One of them, Nellie Forbush, a navy nurse and a down-home girl, falls in love with a mysterious Frenchman, Emile de Becque, only to discover she'll have to take on his two mixed-race children from a previous relationship. Another, marine Joseph Cable, falls for a local girl, Liat, despite her scheming mother.

The race angle, which was so strong in the original that bits were watered down before the show premiered, didn't help the show's career. The civil rights movement was barely warming up in the US at the time and the Democratic convention had just introduced race issues into its political platform.

"So the conversations were in the air at the time, and they're in the air again," Sher says. He has restored inflammatory moments that were cut to make the piece more palatable and has carefully segregated the black from the white servicemen on stage. It ramps up the implications of American foreign policy and of Americans' experience of themselves.

"It's a very political point of view. How is it that Americans, maybe like Australians, were isolated as a country, and our engagement with otherness abroad was limited? You drop these people on this island, they meet the islanders and their heads blow up."

Sher first staged this production in 2008 for New York's Lincoln Centre, where he is resident director. It was 60 years after the play's premiere and the year Barack Obama ran for president. When Sher started looking at the script, he asked himself what was the most moving aspect of it. "I thought the real question was, 'Who gets to be in your family?' "

He doesn't just mean a nuclear family but a country as a whole. "I think that was the question on the table in America: who's really in our family? Who's with us? And when we look at the gay marriage issue now the whole question comes up again."

Sher talks quickly and his words tumble out not quite grammatically, as though his mind is way ahead of them and they have to fend for themselves. He is interested in ideas, the philosophical and political motivations behind the craft of theatre, and it's not surprising his roots are in experimental drama.

He didn't grow up with the arts, though his older brothers took him to see the Grateful Dead, he says deadpan. There was enough drama unfolding in his own life, however, to give him first-hand insight into the kinds of things - human nature, say, or power relationships - that theatre teaches us about from a safe remove. His father, an insurance broker whom he described to The New York Times as a "brilliant businessman, very charismatic", was also a serious philanderer who had a second family with another woman. Sher's childhood was marked by a drawn-out divorce. He also discovered that his father, who was thought to be a Catholic born and bred, was actually Jewish.

His mother soon met a Chinese-American man, Doug Chang, who moved in, helped rear the family and brought them much needed stability. Sher's lessons in interracial solidarity were formed early and you can see why the question of who gets to belong is vital to him.

He learned other lessons in childhood that might have precociously ratcheted up his quotient of emotional intelligence. When he was six his skull was crushed when it took the full force of a baseball bat in a friendly beach game. He needed two operations, including the graft of part of his rib bone into his head. Six years later, both his legs were snapped in a skiing accident. After three months in casts, he immediately snapped a thighbone in a water fight with one of his brothers.

Though he and his wife, actress Kristin Flanders, have only one daughter, Lucia, his thought patterns seem indelibly formed by membership of a tribe. It's what turned him away from writing, which he started early, to directing, for example. "Writing is very solitary. I like being a part of the family, and leading, and editing, and pulling the other people's ideas and helping shape performances, and unifying the designers. I work with the same people over and over again; that appeals to me a lot. I really love that."

He wrote his master's thesis on avant-garde Polish theatre director Tadeusz Kantor and began his career in that vein. He was director of Intiman Theatre in Seattle, a company devoted to collaborative, risky ventures, between 2000 and 2010. Among his productions were the premiere of Nickel and Dimed, a play based on Barbara Ehrenreich's undercover expose of the lives of America's poor; Tony Kushner's Homebody/Kabul, which brought a British housewife up against the reality of the war in Afghanistan; and Nora, Ingmar Bergman's edgy take on Ibsen's A Doll's House. Reinterpretations of Shakespeare and Carlo Goldoni also featured.

"My experimental [approach] is from the inside, not from the outside," he says. "I try to get in the middle of [a play] and crack it open, so that, as you're pulled along inside the context of it, you're suddenly released into something you didn't expect."

His biggest hero as a director, he says, is Giorgio Strehler, an Italian who practically invented the role of theatre director in Italy. He was a friend of Brecht who directed the premiere of Camus's absurdist play Caligula and is often compared to 20th-century theatre giants such as Peter Brook and Bergman. "That kind of thing is my ideal, where it's deep and profound and big, but it's from inside," Sher says. "Whereas a Peter Sellars, who is also a great director, is going to do Don Giovanni in the Trump Tower and it's going to be this crazy thing and feel very different. He's trying to get inside it from a different point of view."

In 2008 Sher was appointed resident director at Lincoln Centre and commuted between there and Seattle, which was not so conducive to family life. He is based permanently in New York now but his need for variety is finding a new outlet. He has been doing more and more musical theatre, including a version of Pedro Almodovar's Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown in 2010. It was pretty universally panned by the critics.

His South Pacific, by contrast, was a triumph. The critics loved it, audiences came for two years and it won a sheaf of Tony awards. For the past year it has been touring in Britain, where it has been nominated for four Olivier awards. The Australian production, which opens in Sydney tonight before moving to Melbourne in September with Brisbane to follow, stars Kate Ceberano, Lisa McCune, Teddy Tahu Rhodes and Eddie Perfect.

Although they all sound just right for their roles, Sher says casting wasn't easy. It wasn't easy for the 2008 US production either: the process took 15 months. "We realised that we were going to have to make it better than the original, so it would overlay the original," the notorious perfectionist says. "For it to be a piece that was deep in the memory, we had to make it that good at every possible level."

The issue of race stalked him almost as strongly as it stalked Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein who, in the 1950s, were accused of introducing communist ideas and threatening America's way of life. "Instead of doing colour-blind casting," Sher says, "I thought, 'I'm going to leave them segregated on stage because that's how it would have been.' On stage they're always on their own, they're always kept separate." It is same here in Australia. "You realise that, OK, the racism in the world was part of the world. It's not just Nellie's problem. Everybody lived in a world which was fundamentally grounded in forms of racism." There are plenty of people who would find those sentiments inflammatory in 2012, let alone 1949.

One of the hallmarks of Sher's version of it is the clarity he brings. The original he says, was "a little old school, a little bit heightened, but if you strip those layers away, there is still a lot there. Mine is like a cleaned portrait." There is indeed no unnecessary business on stage, no camping it up. In fact, it looks as though it must be relatively simple to stage. Sher pulls a face. "No, it's not so simple," he says with a nervous laugh.

What makes it more difficult in this instance is that he's working on South Pacific for an opera company, and opera happens at speed, unlike musicals, which are expected to have long runs. (South Pacific is going on to have a commercial run, but for the moment the imperatives of an opera company prevail.) OA has allowed him the rare privilege of four previews before tonight's official opening.

For all the exigencies of opera and musicals, the art form has one great asset that plays lack and that is of huge help to the director: music. "If I do an opera, I have emotional support from 80 people in the pit, who are playing constantly, so I don't have to build in the rhythm," Sher says. A great part of the emotional work, in other words, is being done for him. "I look at singers of opera as great athletes, like they'd be the best player in an Australian football team, and you train and train and train, then you go out and throw yourself into the game. Whereas an acting process is a slower, more painstaking thing, which you have to sustain eight times a week in a particular way, unsupported by an orchestra and a sound track."

He says he couldn't do music theatre - opera or musicals - full time; it would send him crazy. But it keeps calling to him. His conception of Craig Lucas and Adam Guettel's musical The Light in the Piazza earned him a Tony nomination for best director of a musical in 2005. He staged Gounod's Romeo et Juliette at the Salzberg Festival and, although some local critics had a fit, it has been immortalised in a Deutsche Grammophon DVD. He made his Metropolitan debut with a production of The Barber of Seville in 2008, the same year as his South Pacific.

Now, as well as some straight theatre coming up, he's working on L'Elisir d'Amore for the Met, and they can expect to see something deceptively simple there too. "I've seen so many thousands of whacked, insane productions, and I just couldn't do it," he says. "So it's [set in] 1846 in Italy."

Sher's training is in text and he doesn't read music, which is no hindrance in his opinion. "I actually have a friend I've worked with for 30 years" - that family thing again - "and we go through every note, and I write out all the notes in my own language." He means it literally: he has the libretto and annotates his version of musical notes alongside it so that he knows when notes sweep up or down, a note is sustained for a few seconds, or a sequence gets sung prestissimo.

"I think when a stage director is looking at a score, he's not seeing the scene," Sher says. "The scene is laid out differently on the page. I think when you work with a music director, he should be looking at the score and you need to be looking at the scene." Which must be music to the ears of conductors who have had legendary rows with out-there directors who try to direct the music as well.

One of his biggest aims is to merge recitative and aria seamlessly, "so that when you get to an aria, you have a reason to sing it, as opposed to you get to an aria and you just listen to how well it's sung". In a way this is a merger of all his interests in the performing arts. "Especially in something like South Pacific, the best versions of it are when you can't tell the difference between the text and the music. That's what I'm always searching for."

South Pacific opens in Sydney tonight; Melbourne, September 13 to November 4; Brisbane dates to be announced.