How poor women who take small loans can end in prison

Microloans were sold as the savior of poor women in developing countries, but all has not gone to plan.

I first heard about microfinance when I was about 16, working as a volunteer on community projects. A mentor advised me to read, among other things, Banker to the Poor, by a Bangladeshi economist named Muhammad Yunus.

I had never heard of Yunus, or microcredit, the term he used to describe lending small amounts of money to poor women, a way to help them become self-sufficient.

Yunus insisted that microcredit could end poverty. By giving women just a few dollars, they could start small businesses, then use those profits to take care of themselves and their families.

Focusing on women would not only bring one of the most marginalised groups into the economy. Yunus claimed that, thanks to their sense of duty as caregivers, their success would also mean the success of their children, their communities.

He also argued that they were more responsible than men, more likely to use the money well and repay on time. Through something as simple as a small loan, Yunus claimed that gender equality could be achieved, economies and neighbourhoods strengthened.

He had developed this idea in the late 1970s, after visiting a village in Bangladesh called Jobra, where he met a twenty-one-year-old mother of three named Sufiya Begum, who was working from her home.

He found Begum “squatt[ing] on the dirt floor of the veranda, a half-finished bamboo stool gripped between her knees.”

They got to talking and Yunus learned that she was making stools with bamboo that she could only purchase after borrowing five taka – about 22 cents at the time – from local middlemen. At the end of each day, the same middlemen bought her bamboo stools for 24 cents. Thanks to this arrangement, she was making only about 2 cents a day.

Yunus knew that he could ease her burden by just giving her the 22 cents himself – “that would be so simple, so easy” – but he resisted the urge, since “she was not asking for charity”.

A loan, he believed, “could bring her that money. She could then sell her products in a free market and charge the full retail to the consumer.”

But there was a problem: there was “no formal financial structure … to cater to the credit needs of the poor” in Bangladesh. Getting a loan from a bank was out of the question since Begum was a woman. What’s more, loans were given mostly to wealthy landowners.

Yunus decided he would do what the banks would not. He would lend to poor, asset-less, landless women like Sufiya Begum, who had been deemed uncreditworthy. With a small team of research assistants, Yunus made a list of Jobra villagers who relied on middlemen or moneylenders.

He lent a total of $27 to forty-two different women, an act that would be recounted numerous times over the next several decades: in the New York Times, the Guardian, the BBC, in academic papers, at conferences; by Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, and at rock concerts.

At Oslo City Hall on December 10, 2006, when he accepted the Nobel Peace Prize, Yunus told princes, kings, queens, and the hosts of the evening, Sharon Stone and Anjelica Huston, “I offered … $27 from my own pocket to get these victims out of the clutches of those moneylenders … If I could make so many people so happy with such a tiny amount of money, why not do more of it?”

Despite how famous the story of Muhammad Yunus’s first loan would become, soon after giving the $27 to forty-two women, Yunus considered the action “ad hoc and emotional”. The right thing to do, and a good proof of concept, but a bit like firing from the hip. Next, he thought, “I [need] to create an institutional answer that these people could rely on.”

By 2010, just around the time I graduated from college, microloans were everywhere. And then they seemed to disappear, so much so that by the time I moved to Sierra Leone, West Africa, in 2015, to take a job with a health organisation just as the country was emerging from the largest Ebola outbreak in world history, I had almost forgotten about them.

A couple of years into my stay, I was speaking with a colleague about her previous job at a legal aid organisation called AdvocAid, which assisted women who were taken to the police and sometimes prison for failure to pay their loans, including at times their microfinance loans. I have a vivid memory of how surprised I felt: of course, that women were finding themselves entangled in the legal system for small unpaid debts. But also: that microfinance still existed, that people – many people, according to my colleague – were still taking out these loans.

I remember saying something to the effect of, “I kind of forgot about microfinance!”

My colleague, appropriately, snapped back, “Go ask anyone here, many people take it.”

Later that afternoon, I walked across the street to the fruit and vegetable vendor I often bought cabbage, mangoes, pineapple, and coriander from, asking her if she knew of anyone who had taken out such a loan.

She, too, looked at me like I was an idiot. “Yes. I’ve taken out many. Many! Every few months. In fact, I have a few right now.”

I asked whether she had ever heard of anyone going to the police when they couldn’t pay back.

She hesitated. She insisted she had never had a problem herself but had heard of other women who had, those who, as she put it, “weren’t very careful.”

Somehow, I had only paid attention to one side of the equation: those who talked up the astounding promises of new anti-poverty programs like microcredit. I had completely ignored the other side: the people who experienced those programs in their day-to-day lives, who lived with them long after books and celebrity campaigns promoted them.

I wanted to know more. To understand how and why microfinance became so popular in the West, how its narrative changed – why it is I suddenly stopped hearing about the tiny loans – and how these changes continued to impact the lives of borrowers around the world, long after so many of us had forgotten about Muhammad Yunus’s promise that they would end poverty.

And I wanted to know how women themselves understand these loans. I started by interviewing the staff at AdvocAid, the legal aid organisation my colleague had worked for.

I also met women who were awaiting trial or in jail, and those who had already been in prison for unpaid debts, sometimes for years, often without an official trial. I wanted to know not just about entanglements with the legal system but about how the debts functioned in the local economy and their lives.

I went to markets across the country, asking what must have seemed like inane questions to fruit vendors and sellers of used clothes.

Where do you get money for business? How much do you sell this T-shirt for? Why did you set that price? How did you decide which microfinance company to borrow from? Where did you borrow from before? How do you use money?

I spoke to around a hundred market women that summer of 2019. The majority had taken out microfinance loans. Their experiences varied widely, but all were built on hope, a series of “ifs”. If I had money; if I had a bigger business; if I had a fixed location to sell my wares from; if I could buy goods from China and bring them directly then life would be better.

For some of the women, the ifs had borne out. Out of the hundred I interviewed, I met three who said with certainty that they had been able to expand their businesses thanks to a microfinance loan. One had been able to leave her husband, who became abusive after he learned she was HIV positive. She used the money to start a successful fish business, eventually remarried, and had enough money to comfortably take care of herself and her kids.

But I met many more women who complained about the loans: that the repayments were too high and came too fast or that they ate into their profits, essentially nullifying any business growth. To help make payments, many had taken out multiple loans, one to pay off another, from multiple sources: different microfinance companies, their husbands’ bosses at work, another trader – a balancing act that seemed at once to be working, in that they were staying above water, but was also immensely stressful.

Every single woman was clear-eyed about the risks of debt. They had seen friends go to jail, neighbours or family members who had left their homes and communities when they could not pay off a loan. But they also described tangible benefits – not of launching successful businesses that propelled them out of poverty, as Muhammad Yunus promised, but more basic wins like covering school fees and annual rent. Nearly every woman said: we can’t really manage with these tiny loans, but we can’t manage without them either. These women were terrified of the loans and their consequences – and also terrified of life without them.

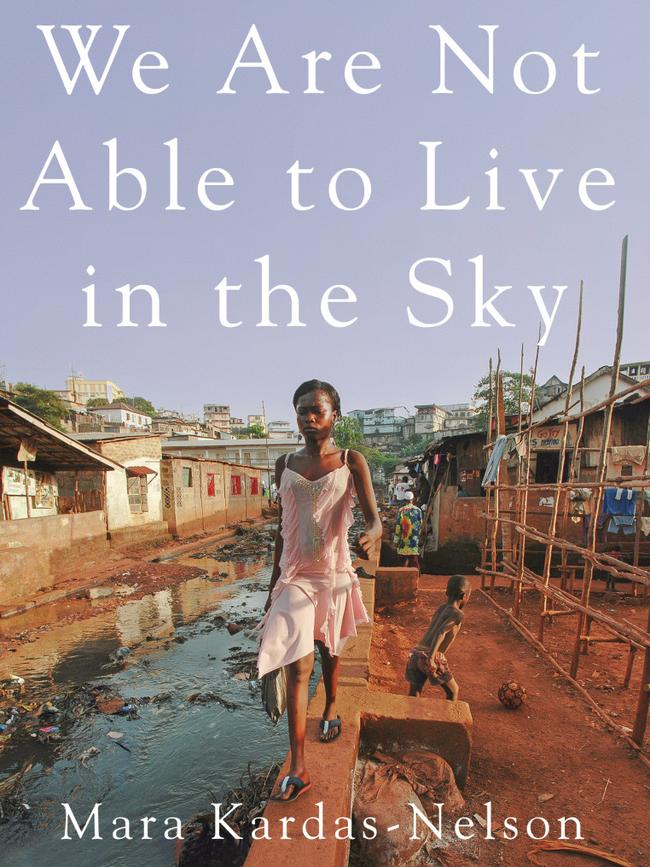

This is an edited extract from We Are Not Able to Live in the Sky (The Seductive Promise of MicroFinance) by Mara Kardas-Nelson (Scribe) out now.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout