Avant-garde’s call answered by Heide show on constructivism in Australia

The idea that the avant-garde had some affinity with revolutionary politics is beguiling but misleading.

One of the most beguiling yet misleading ideas in 20th-century art was that the avant-garde had some inherent affinity with revolutionary politics — that there could be parallel revolutions in the socioeconomic and the cultural-spiritual spheres.

This dream began with the Russian Revolution whose centenary, as mentioned a couple of weeks ago, is marked this year. More exactly, the tsar was overthrown, after a series of military disasters in the Great War, in March 1917 (February in the Julian calendar), and the provisional government was in turn overthrown by the Bolshevik coup of November (October in the old calendar).

For the left, up to the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989, this revolution remained an epochal and almost sacred event in world history. But there were other revolutionary movements that also promised to introduce new eras for humanity — fascism from the 1920s and Nazism in the 30s. All of them had complicated relations with art and in all three cases, but especially under the Nazi and Soviet regimes, artists became collaborators in the crimes of their governments.

The Nazi case was the simplest. The regime was opposed to modernism and pilloried it in the notorious Entartete Kunst exhibition of 1937. Artists sponsored by the Nazis tended to produce straightforward works of propaganda and kitsch.

In Russia, the revolutionary government was initially friendly to artists eager to join in the great adventure of creating a new society, but under Stalin modernists were banished because their concerns were too arcane and incomprehensible to the masses. Instead the regime turned back to the academies and marshalled them into the production of mass propaganda images — a model later copied by the Chinese.

Italy was the only totalitarian regime that tolerated and, especially in architecture, welcomed modernism. Mussolini declared it was not the state’s business to interfere in artists’ work, resisting the suggestion he should follow Hitler’s example in proscribing the work of the avant-garde. Certain artists were persecuted, however, if they opposed fascism openly.

In France and the English-speaking world, left-leaning intellectuals and artists looked at the Soviet Union through rose-tinted glasses for decades. Even reports of Stalin’s atrocities were insufficient to dispel illusions of a workingman’s paradise. And there were repeated attempts, inevitably ending in divorce, at a marriage of contemporary art movements with homegrown communist parties.

The most famous of these, perhaps, was when Andre Breton decided that the surrealist movement was a revolution of the mind that echoed — or, in the French context, prefigured — a social revolution. So the surrealists duly joined forces with the Communist Party, only to discover to their chagrin that they were not treated like star recruits; the communists, for their part, soon concluded that the surrealists were just spoiled middle-class boys whose idea of liberation was essentially onanistic.

We had a repeat of this mismatch of avant-garde and political radicalism in Melbourne during the years of World War II, when the Contemporary Art Society was divided between avant-gardists such as Nolan, Tucker and the Reeds, who believed in formal experimentation, and communists who preferred a realistic style capable of speaking to ordinary people.

This exhibition considers the stylistic developments that arose in Russia in the years leading up to the revolution and immediately afterwards, before the increasing pressure of censorship and eventually outright suppression under Stalin. Above all it focuses on the influence of this art on Australian artists, especially in the 80s, but also before and since.

Samples of the work of Malevich, Rodchenko, Lissitzky and others are included in the exhibition. They created a vein of abstract art that was not romantic and spiritual like the form developed by Kandinsky in the same period but, as the word constructivism implies, built up of elements, usually geometric and hard-edged.

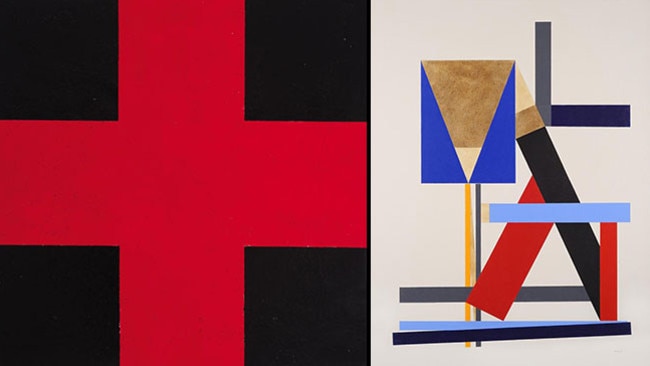

The resulting pictures are not without some vestigial references to the world, but they are primarily ideal inventions, geometrical ideas that are the work of mind, not of nature and organic processes.

Thus Rodchenko’s Composition (1918) is painted on a panel composed of several boards joined to form a subtly concave surface. The work is thinly painted in oils so it leaves the woodgrain visible in many places; the palette is muted greys and browns borrowed from analytical cubism — as is the style of paint application — but the forms are imaginary ones that curve and intersect and weave into each other.

Similarly, the little untitled drawing by Malevich (from 1915) included in the exhibition is a play of forms that generate their own virtual space, each with its own qualities of mass and density, position with respect to each other and implied velocity.

El Lissitzky’s lithographs are less spontaneous than the Malevich drawing and have less physicality than the Rodchenko painting. They are linear, quasi-geometric structures that come into being through the artist’s work and become, as it were, new objects in the world, a supplementary creation in addition to the works of nature, but without the utilitarian purpose of other creations of the human hand.

Ultimately, despite the ostensible interest in politics, society or popular accessibility — almost always illusory in modernist art — these formal aesthetic games are the most extreme forms of art for art’s sake. The exhibition label quotes Lissitzky: “From being a simple depiction, the artist becomes a creator of forms for a new world — the world of objectivity.”

A creator of forms, indeed: it is that pleasure in creating ideal objects, things that exist only as the inventions of the human mind, although how or in what sense these things are meant “for a new world” is questionable, as indeed the communists saw perfectly well. The turn towards the radically ideal is inevitably a turn away from the problems of the real world, whatever one may tell oneself.

Equally, or even more naive, is the expression “simple depiction”. This is to assume reality is something that can be copied in a straightforward way, and since the only things that can be copied in this way are things of the same nature, it is to assume reality is already an image. But nothing could be further from the truth. Even at the most obvious level, “depiction” involves translating a mobile, three-dimensional world of things, encountered by a living and affectively engaged observer, into a flat pattern of images produced in a limited range of pigments that are themselves different in nature from the object.

If we look more closely, however, it becomes infinitely more complex: the world of things, as we see it, dissolves into a reality in which entities formed of atoms and molecules have variable capacities to reflect light, which is then analysed by our perceptual system to produce what we know as colour, while our sense of three-dimensional form develops to inform these purely visual data, through the experience of moving in the world of objects and space as infants.

And that is without even discussing what happens when we encounter another person or indeed any living thing, animal or even plant: for here we discover not only an object like others in the world, but a living presence we can recognise as in some respects like ourselves. In short, there is nothing less simple than making a depiction of things and living creatures and fellow humans.

In contrast, for all the pleasure of making artificial patterns, this is a drastically limited activity, as the exhibition makes all too clear. This is why the most interesting of the later works are in photography, for here the artist is again engaging with a world that is full of inexhaustible interest, whether in the productions of nature, or, especially in this case, the works of human industry, as in the photographs of Wolfgang Sievers.

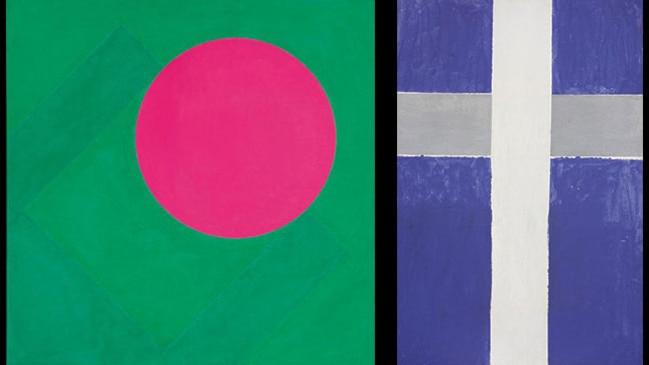

With the large-scale abstract paintings, some of the simplest ones, like Gunter Christmann’s cross, have an interesting play between flat geometry and implied space, but that interest is limited, and today the picture is almost more appealing for its nostalgic, even naive qualities than for any real aesthetic depth.

Many other large abstract compositions are simply dull. Some of the smaller works, even when superficially interesting, ultimately have the character of doodles: a kind of bricolage with extremely limited resources, which can only ever produce a narrow and ultimately sterile set of permutations.

Sculpture is sometimes more interesting in this regard, because it has more dimensions to work with, as well as a wider range of materials. Margel Hinder’s wall sculpture stands out, and to a lesser extent Justin Andrews’s series of three-dimensional assemblages dedicated to the main Russian figures of this movement. Among the earlier Australian artists inspired by constructivism, Frank Hinder is the most interesting; Grace Crowley and Ralph Balson’s work has an indecisiveness that is incompatible with a style of clear forms and lines.

More interesting was the revival of interest in constructivism during the 80s, which is in a way the main focus of the exhibition, with figures such as John Nixon and Melinda Harper. But of course these artists did not simply repeat the earlier style. Art history is full of cases of renewed interest in earlier moments in art, but the second iteration is always, of necessity, very different, in much the same way that Proust said a book represents an end for its author but a beginning for its reader.

Historical and cultural circumstances, above all, are never identical. The constructivists emerged in the political world of tsarist Russia and an art world dominated by the academic tradition. The neo-constructivist artists of the 80s arose in a modern consumer society where art was dominated by fashion and the market for commercially successful modernist work.

Their work, in trying to distinguish itself from this commercial production, has much in common with the earlier and contemporary anti-commodification movements of conceptualism and minimalism. Thus Nixon’s emphatic red cross on a black ground is painted on cardboard, left raw and visible at the edges. The image is striking but the material support is deliberately flimsy.

In Harper’s painting of a cross, the two bars are of different hues of grey, and the horizontal one is clearly in front of the other, so that the form decomposes and loses its symbolic charge. The remaining elements of the image are not even joined as they are in Nixon’s cross, but left hovering in proximity. Above all, the contingent, material character of the painting is left visible.

This is not the image, as in the earlier period, of an ideal creation of the mind, but of a concrete, imperfect work of the hand.

Call of the Avant-Garde: Constructivism and Australian art

Heide, Victoria. Until October 8.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout