Australiana exhibition at Bendigo Art Gallery presents eclectic look at identity

The planning of ideal states can be an intellectual exercise – the imagination of utopia – or a political project, but no artificially designed nation has ever been successfully realised.

The expression “designing a nation”, the subtitle of this exhibition, Australiana: Designing a Nation at Bendigo Art Gallery, could be taken in a trivial sense, as the displays of fashion designs and bedspreads might suggest, but it is surely to be understood also more seriously. In that case, though, it begs the question: in what sense was Australia designed? The planning of ideal states can be an intellectual exercise – the imagination of utopia – or a political project, but no artificially designed nation has ever been successfully realised.

Nations are complex organisms, composed of political systems, legal institutions, economic structures, educational and training organisations, social and cultural habits, values and beliefs. They evolve through a process that is partly organic and rooted in their history, partly the result of critical reflection and deliberate reform, often in response to pressure from a particular class, group or political faction. One of the most valuable things that the new nation of Australia inherited from its founding mother-nation was a political model based on the assumption of continual open-ended reform and adjustment.

The “designation” of Australia however, including its very name, is much older. A wall panel at the opening of the exhibition implies that the name “Australia” begins with Matthew Flinders; he was indeed instrumental in replacing “New Holland” with “Australia” in common use, but the idea of the south land is very ancient, and as I have mentioned before, long predates the first European footsteps on the continent.

Geographers in Antiquity postulated the existence of a southern continental mass to balance those of the northern hemisphere, and so “Terra Australis” appears on maps well before Europeans had ventured into the southern hemisphere, and many centuries before they even knew of the existence of the Pacific Ocean. It was only two and a half centuries ago that Cook was ordered to explore the South Pacific in case there was another, yet unknown southern continental mass.

The exhibition is arranged in more or less chronological order and is eclectic in taste, as I have already hinted. In the earlier sections, works of art are quite well matched with contemporary furniture, silverware and other items, as well as Aboriginal artefacts. Later there is a lot of fashion which you can safely ignore if frocks are not your special interest. Ironically the room most dominated by dresses is one whose wall panel is titled “Art everywhere”.

Considering the title of the exhibition, it is a little odd that there are so few colonial works documenting the growth of the new settlements; the rapidity with which cities such as Sydney first, and then later Adelaide and Melbourne, were built from nothing was naturally a source of considerable pride to the early settlers and such images were also used to encourage migration and demonstrate the promise of the new land. Today, of course, there is some angst about celebrating the growth of colonial cities.

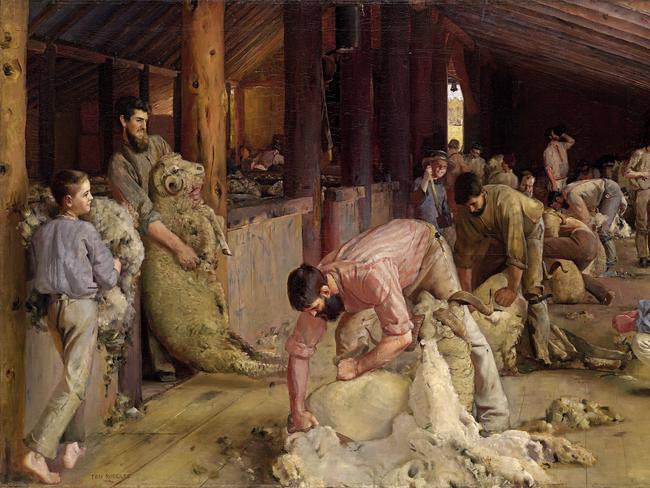

Perhaps this also explains the other odd thing about this exhibition, the relatively poor representation of the Heidelberg School. Tom Roberts’s famous Shearing the Rams (1890) is included. But there is much less emphasis on the theme of the rural settler, as in Streeton’s The Selector’s Hut (1889). For it is above all this group of painters who convey a sense of belonging in the land, of having made this strange and distant country our new home. But no doubt the curators were ill at ease with the idea that any settler could develop an intimate affinity to “country”.

On the other hand, we may also be surprised by the scarcity of pictures of Aborigines, who are an important theme in Australian art from the beginning of settlement to the second half of the 20th century. The way they are represented from the earliest days is a rich subject; their virtual disappearance in the decades leading up to Federation is notable; and the reasons for their reappearance after WWII in the work of Drysdale and Boyd deserve reflection. But this material, too, has been almost entirely omitted, presumably because of some discomfort about the representation of the Indigenous population by outsiders.

Deep discomfort is certainly expressed in the moral squirming and hand-wringing of several labels, particularly one accompanying a 1799 engraving by Thomas Gosse which purports to represent Governor Philip’s founding of the colony of Sydney in 1788. It has the odd title The founding of the settlement of Port Jackson at Botany Bay, New South Wales, no doubt explained by the fact that the colony was meant to be set up at Botany Bay, but Philip moved it, shortly after the first landing, to Port Jackson and the bay which is now Circular Quay.

It is reasonable to point out the artificiality and awkwardness of the composition, and the presence in the background of buildings which were clearly not erected until a couple of years later.

It would have been interesting to show how certain attitudes are borrowed from canonical works of art – thus the kneeling figure on the right is taken from Poussin’s Crossing of the Red Sea, now in the National Gallery of Victoria but then, since 1741, in the collection of the second Earl of Radnor.

But the suggestion that this print was meant to assuage some alleged anxiety about colonial expansion is anachronistic. And the implication that the settlement of Sydney was based on the principle of “Terra Nullius” is a mistake; that legal doctrine was only invoked half a century later, and not, contrary to what is usually assumed, with the aim of dispossessing the native population but of curbing the power of wealthy and exploitative squatters.

Nor was the landing or the founding of the first colony either at Botany Bay or at Port Jackson a “brutal episode” as claimed on the label. There was no violence on either occasion; Philip, like Cook, was committed to treating Indigenous people decently and insisted on the rule of law. Confrontations arose in the Sydney Basin as the settlement spread and as colonists began to occupy lands traditionally used as hunting grounds.

This series ends with the statement that such images exacerbate “colonial trauma” for indigenous people.

This label points to a significant problem that affects Australian museums at the moment; instead of historical expertise and open-minded commentary, we are fed ill-informed ideology and encouraged to share in futile breast-beating about our own history.

It is clear that from such a beginning we cannot expect serious historical insights from the rest of the exhibition. There will be superficial commentary about successive periods, attempts to redress gender imbalances and of course the presentation of colourful fashion and large Aboriginal paintings as some kind of redemptive consummation.

As long as we recognise everything that has been omitted or tacitly censored, the exhibition still presents a number of individual works that deserve our attention, including some good works of the colonial period, notably by Glover and Von Guérard, several small paintings by Streeton, Lost (1886) by Frederick McCubbin and of course Shearing the rams by Tom Roberts.

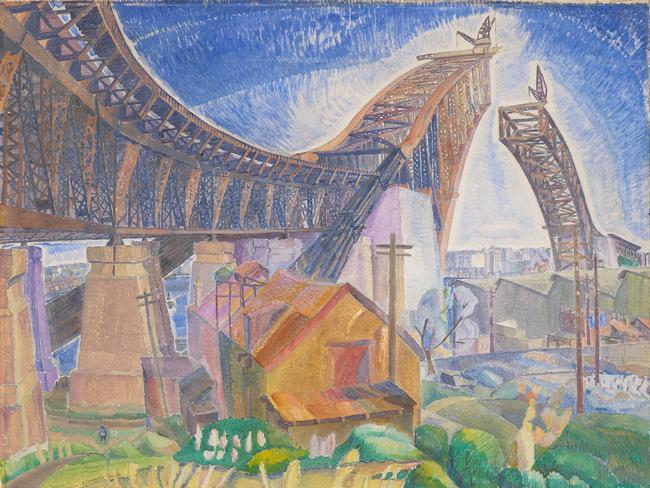

There are several notable pictures of the 20th century, too, but their very significance seems to draw our attention to the lack of any meaningful or authentic thematic structure in the exhibition. The earliest of these is Cossington Smith’s The Bridge in-curve (1930), a statement of optimism and a celebration of forward-thinking at the depth of the Depression, but which loses much of its resonance when isolated from the history of images of Sydney.

Russell Drysdale’s The rabbiters (1947) is a masterpiece of its time, with its strange existential landscape of colossal rocks and a dead tree, fallen into an incongruously upside-down position, and its anonymous human figures, engaged in a futile hunt for the rabbit that has already escaped. But this picture cannot be properly understood outside the development of Australian landscape painting, with its quest to come to terms with the new land and establish a way of dwelling in it and making it a new home.

The climax of that long 19th-century process was reached with the Heidelberg painters, as already mentioned, and had its epilogue in the work of Hans Heysen and other important landscape painters between the wars. The discovery of the arid and almost uninhabitable outback by Drysdale, as well as Nolan and Boyd, during and after WWII, created another symbolic and existential landscape, which not only came to evoke an aspect of the Australian experience but more broadly seemed to epitomise a state of postwar anxiety and desolation.

In Drysdale’s painting, the great dead tree with its nightmarish tangle of dead roots is a grim inversion – figuratively and literally – of the landscapes of Heysen, whose mighty gum trees become emblematic of the land itself. But there is little sense of the history of Australian landscape that Drysdale inherited, nor of the discovery of the outback as a new symbolic site in the history of Australian self-consciousness.

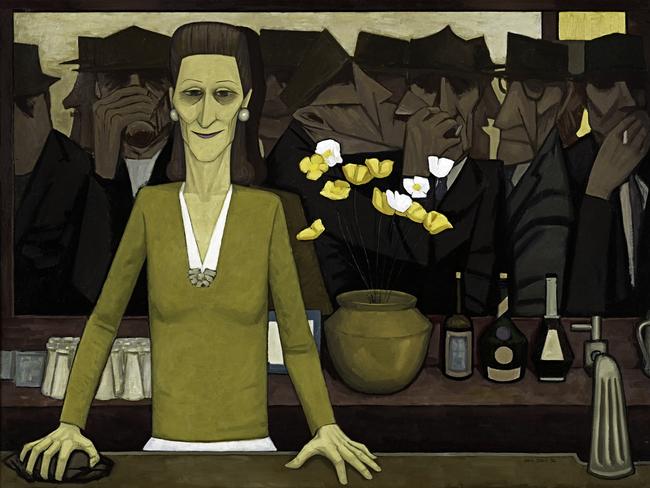

Nor is there any context for John Brack’s The bar (1954), which among other things reminds us – like others works by Brack – that although we think of our national character as rooted in the bush, most Australians have long lived in a few big cities.

At least the label for this work does explain the dreary habit of the “six o’clock swill” and acknowledges that the artist is openly citing one of Manet’s last great paintings, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882). But it should mention too that, as in Manet’s original, the background is a mirror, so that the crowd is not behind the barmaid but in front of her. Like Brack’s other masterpiece, Collins St, 5pm (1955), this picture is deeply imbued with the spirit of T.S. Eliot. The barmaid recalls the one in The Waste Land (1922) who says “hurry up please it’s time”, and the melancholy drinkers, reduced to shadows in their reflection, are The Hollow Men (1925). This is an expression of the modern experience rather than specifically an antipodean one, but it still says more about our nation than the bright commercial “Australiana” that dominates the latter part of the exhibition.

Australiana: Designing a Nation at Bendigo Art Gallery, until June 25.

Australiana: Designing a Nation

Bendigo Art Gallery, until June 25