Artful meeting of East and West

This exhibition shows how leading artists Cressida Campbell and Margaret Preston melded Japanese printing techniques with an Australian aesthetic.

Since the invention of printing and the development of printmaking techniques such as woodblock and engraving, followed later by etching and other methods, prints have always been loved by collectors and sophisticated art lovers.

From Durer’s engravings to Rembrandt’s etchings or Goya’s aquatints, connoisseurs have appreciated the different aesthetics of the various media and techniques, and eagerly studied variations between states and the qualities of individual impressions. All important art museums have traditionally had dedicated print galleries in which masterpieces from their collection could be displayed.

Today, gallery audiences are much less visually literate. I mentioned recently the contrast between the NGV’s superficial and populist Triennial and a substantial exhibition, largely drawn from the same institution’s collections, at the Hamilton Regional Gallery, which happened to make excellent use of prints. Of course, the NGV long ago closed its own print gallery.

Fortunately, Geelong Art Gallery has taken an active interest in prints and printmaking in recent years, no doubt in part because of the substantial holdings it acquired through the Colin Holden Bequest. A couple of exhibitions drawn from that collection have already been reviewed in this column: A Tale of Two Cities (2022-23) and Graphic Investigations (2023), as well as the NGA touring exhibition Spowers and Syme (2022). They also have an annual print award exhibition.

Currently the gallery is showing a small but interesting exhibition of works received in another gift (2019), from Conrad O’Donoghue and Rosemarie Kiss; it contains fine examples of works from the 17th to the 20th centuries, including by Salvator Rosa, Goya, Whistler and Rick Amor.

The main exhibition currently showing at Geelong, however, is devoted to Japanese prints and their influence on two Australian artists who are probably not usually thought of together, and yet who were both inspired by the coloured woodblock prints of the ukiyo-e tradition: Margaret Preston and Cressida Campbell.

Japanese woodblock prints are relatively recent in the history of the art of Japan. Unlike the courtly art of earlier centuries or the sumi-e ink painting of the Chinese scholarly tradition, this was a new form that arose in an increasingly urban society from the late 17th century onwards. Prints are multiples and are thus more accessible to a middle-class audience, and they were produced in large numbers even though the classic ukiyo-e technique demands extraordinary technical skill and expertise.

The earliest woodblock prints were much simpler than the ones with which most people are more familiar. They were printed in black ink and sometimes hand-coloured afterwards. The exhibition includes several examples of this process, which is incidentally relevant to the art of Preston, whose works, as we will see, were almost all hand-coloured. Soon, however, prints were produced from multiple blocks: the first was printed in black, but separate blocks had to be cut for each colour, and precise registration in the printing of the successive blocks was essential.

The subject matter of ukiyo-e prints included landscapes – but views of specific places, not the ideal poetic landscape of the ink painting tradition – as well as portraits of beautiful courtesans or tea house girls, and portraits of male actors, whether in costume in a male or female role. These subjects in particular evoke the “floating world”, the approximate translation of the Japanese word “ukiyo”, which has its roots in Buddhism but by the modern Edo period had acquired connotations of hedonism and was associated with the fleeting joys of the pleasure district of Yoshiwara, just outside the capital.

The exhibition includes a variety of Japanese prints from holdings at the NGV and at Geelong, as well as several items from Campbell’s own collection; interestingly many of these are from the early 19th century, when the colours were simpler and more muted than they became by the mid-century. There are examples of landscapes, most of which are famous views in Edo or picturesque scenes on the road to Kyoto, images of samurai and several of beauties; among these is one of a courtesan hiding a letter she has received in her kimono, and another of a girl sitting pensively, dreaming of her absent lover.

Such prints became very popular in Europe in the later 19th century, after the opening of Japan to the world and during the Meiji Restoration. They appealed to artists from Manet to the Impressionists and to Post-Impressionists like Van Gogh, partly because they suggested ways of constructing pictorial composition with areas of flat colour – a particularly interesting case of two-way cultural exchange, because the ukiyo-e tradition itself, especially in its treatment of space, was influenced by Western perspective. An example here is Hiroshige’s view of Kasumigaseki, in which a dramatic central avenue, orthogonal to the picture plane, plunges into the distance. Japanese arts and crafts also appealed to painters like Whistler and artists and writers of the Aesthetic movement, at the very time that Japan itself was assimilating Western science and technology at an astonishing rate, and indeed Western art as well, as can clearly be seen in late 19th-century ukiyo-e prints. Westerners such as the Greek-Irish writer Lafcadio Hearn and the American art historian Ernest Fenollosa taught in Japanese universities and also helped to bring a new understanding of Japanese culture to the West.

In the last decade or two of the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th, interest in Chinese and Japanese art increasingly spread among authors and intellectuals, including poets such as Ezra Pound and W.B. Yeats; and this was not an isolated phenomenon, for there was simultaneously a growing interest in the cultures, religions and philosophies of the East, from both philological and spiritualist perspectives.

Chinese and Japanese literature became more widely accessible with the translations of Arthur Waley and others; and exhibitions from Boston to Paris and London helped to reveal the history of Chinese and Japanese art to a broader cultivated public.

The Geelong show includes the catalogue of one such exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum (1913-14), as well as books on the technique of Japanese woodblock prints, like Edward Strange’s Japanese illustration: a history of the arts of woodcutting and colour printing in Japan (2nd ed., 1904) and the same author’s Japanese Colour prints (2nd ed., 1908). Most of these books belonged to Margaret Preston, who was the first Australian artist to take an active interest in the Japanese tradition of woodblock printing.

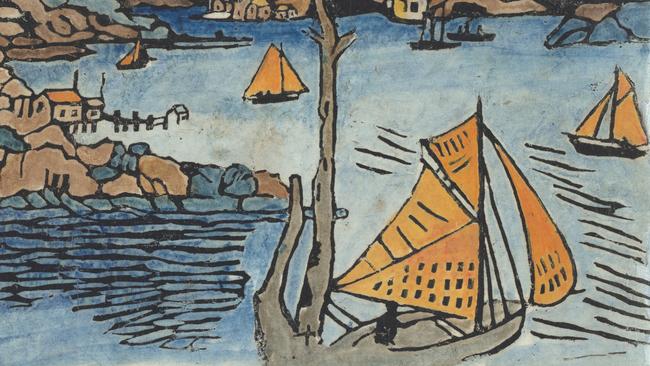

The last room in the exhibition is mainly devoted to Preston’s work, including early landscapes and views of Sydney as well as her better-known floral compositions. These early views of the city, like The Boat, Sydney Harbour (c. 1920), reflect her fascination with Japanese printmaking, and to her contemporaries she seemed to “have put Sydney’s urban environment through a Japanese sieve”.

In reality, however, she had nothing like the technical proficiency of the Japanese woodcutters, and this print is not only unsophisticated in design compared to Japanese art, but also printed from a single block and hand-coloured.

All of Preston’s best-known images are made in this way, and her work is thus technically speaking very simple; and yet these prints are some of the most striking and characteristic images in Australian art between the wars. Their strength lies in their combination of sensitive and accurate botanical observation with the schematic reduction of natural organic subjects to formal design. In this, as one of the wall labels suggests, we can see an echo of the way that ukiyo-e prints also love to contrast geometric and organic shapes.

Campbell also adapts Japanese printmaking in a way that is in fact both less traditional than Preston – in the sense that hand-coloured prints from a single block are one of the forms of ukiyo-e, as we have seen – but also much more technically sophisticated.

As we have discussed at greater length in earlier articles, all her colours are printed, but they are printed from a single block, rather than from a series of separate blocks for each pigment employed.

Campbell begins by drawing her design on the block – actually a sheet of plywood – and then engraves a fine groove along each of her lines. A normal woodblock entails cutting away the surface of the block, leaving only the areas to be printed either in black, for the keyblock, or in one of the subsequent colours.

But since all her colours are to be printed from the same block, she does not remove any significant area of its surface, but simply cuts out fine boundaries between what will be each of her colour areas. This is what gives her prints a subtly abstract appearance, as a composite of distinct elements.

The pigments are applied to the block in thick watercolour, which allows not only for a wide variety of hues but also for nuance and gradation within each area of colour; there is greater variety in the petals of Campbell’s flowers than can be achieved with separate blocks, although some of the distinctive aesthetic qualities that arise from the artifice of limitation are inevitably lost in the process.

When the block is finished, it is re-moistened with water spray, and a single impression on paper is taken. Thus each of Campbell’s works exists in two quite different forms, the original colour block and the paper print. These, as we can see in one pair near the start of the exhibition, are of course mirror images of each other.

The subjects of her prints are often still lifes, including table pieces and flowers, but some of her most characteristic work has been images of the interior of her house, the exquisitely serene and refined environment that she put together with her late husband Peter Crayford. The aesthetic of these pictures, with its lucid attention to detail, precision and yet sensitivity, seems perfectly matched to the sensibility represented by the interior. It reminds one of a beautiful line from Baudelaire, “la, tout n’est qu’ordre et beaute…”: there all is but order and beauty, and as he goes on, luxury, calm and pleasure.

This distinctive world that Campbell evokes, although composed largely of European antiques, furniture and pictures, also includes many Chinese and Japanese elements and reminds us incidentally how many oriental elements have been assimilated, for at least a century, into what we might think of as the English interior.

The unique style of her prints itself speaks of the assimilation, reinterpretation and adaptation of a Japanese tradition, and attentive viewers will recognise in several of the domestic interiors original ukiyo-e prints, including some in the current exhibition. Their presence in her work is like an aesthetic “mise-en-abyme”, a reminder of the ultimate origin of her inspiration.

Cutting through time – Cressida Campbell, Margaret Preston and the Japanese print

Geelong Art Gallery to July 28

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout