Are murals the oldest art form?

The earliest example of mural painting can be found in the ancient images cavemen produced on rock faces in the stone age.

The idea of mural painting as a special category of art seems to have arisen around the middle of the 19th century. It was promoted by the Arts and Crafts and Aesthetic movements, and by some modernists such as Matisse, before being adopted as the vehicle of political propaganda, flourishing especially in totalitarian regimes, and ending up in the swamps of graffiti, street art, interior design and kitsch, as any internet search for the subject will demonstrate.

There is something odd about the characterisation of mural painting as a special category of art, and particularly about the timing of that characterisation. For there is no older art than wall painting; cavemen produced the most ancient images we know on natural rock faces in the stone age. Much later, early civilisations adorned the walls of palaces and tombs with frescoes, some of which survive from as long ago as the Bronze Age.

In the time of Giotto, there were altarpieces and smaller works painted on timber, but large-scale narrative painting was executed in fresco, and for the next four centuries or so it was common for a chapel to have a freestanding altarpiece surrounded by walls decorated in fresco. From the late 15th century altarpieces were increasingly painted on canvas instead of timber panels.

Why then was the idea of mural painting discovered in the middle of the 19th century? No doubt because the old tradition was by then moribund; the last important fresco cycles had been painted in the 18th century by Tiepolo, although as late as the 1850s Delacroix produced murals in oils for the church of Saint-Sulpice in Paris. But at the same time, the 19th century was rediscovering the art of the early renaissance, especially the work of Giotto and the great fresco painters who followed him.

Here were examples of clear, dramatic and touching painted images that spoke eloquently to a community about its shared stories and beliefs.

And it is not surprising that this work made such an impression on contemporary artists and writers. It represented everything they had lost, both aristocratic refinement and popular communicability; the petit-bourgeois class of the 19th century was neither educated nor refined, and it had little sense of the shared stories even of the scriptural tradition; its Protestant religiosity was more focused on cultivating a private sense of guilt.

The new proletarian masses produced by the Industrial Revolution, uprooted from their folk traditions, were in a still more culturally disoriented and derelict state, which is why both public education and the building of churches became urgent priorities in the 19th century. This is also why so many thinkers of the time, like Ruskin and Morris, were concerned with restoring the cultural and spiritual life of the working man, beginning with a new approach to work and craft.

And all of this is related to the effort, following the Great Exhibition of 1851, to improve the quality of craftsmanship and design in England, which led to the foundation of the South Kensington Museum (today the Victoria and Albert Museum), to which was soon afterwards joined the old Government School of Design, subsequently renamed the National Art Training School (1863) and then The Royal College of Art (1896). The Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences in Sydney was established with the same intentions in the 1880s.

It seems that mural painting, like stained-glass design, was introduced into the curricula of these technical colleges as a form of interior decoration rather than as a fine art subject, and of course students at technical colleges did not have access to the same range of teaching as those at art academies.

But the very fact that such a dichotomy could arise at all is highly significant: it would have been unthinkable in earlier centuries.

Looking at Australian art institutions, we can see how the tension between the aims of fine art and applied art play a role in the history of the National Art School, because of its origins in technical education, but not at the slightly later National Gallery School in Melbourne, which was established from the outset as an art academy.

As for so-called mural painting, however, it was reclaimed by the fine art tradition towards the end of the 19th century, before being abandoned to social realism in the 20th.

Puvis de Chavannes (1824-98) was a leading figure in Paris from the 1860s; there were influential models in the German world, especially Gustav Klimt in Vienna (1862-1918). John Singer Sargent’s murals at the Boston Public Library (1895-1919) were important too, but Lord Leighton’s two earlier and vast murals for the new South Kensington Museum, The Arts of industry as applied to war and The Arts of industry as applied to peace (1870-72) held a particular prestige both by virtue of their location and of the painter’s eminence.

As these examples also suggest, the category of “mural painting” obscures the question of the real genre of the pictures in question. One might expect it to refer to the traditionally central genre of history painting, but in practice the new mural painting tended to concentrate on decorative renderings of allegorical subjects. At the lower end, it produced the many dreary personifications of Art and Industry and Commerce that abound in Victorian public art.

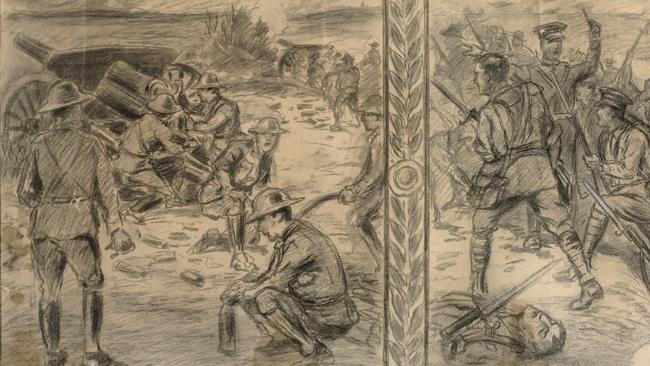

All of this is the background to the main focus of Paul Paffen’s enormous book For the Fallen: a competition was held in 1922 for a painted war memorial above the stairs in the Melbourne Public Library. The commission was effectively awarded, after a poorly handled adjudication process, to Harold Septimus Power, who signed his allegory of war in 1923; this was later balanced by Mervyn Napier Waller’s Peace after victory, painted between 1927 and 1929, although the second work is not discussed at any length in this book. Paffen has done an immense amount of important research into the background of this commission and of everyone connected with it, even if sometimes it seems rather tenuously. Thus there are substantial chapters devoted to individuals such as Walter Rowbotham, including his experiences as a teacher in a technical art school in India, George Dancey and Clewin Harcourt, mostly rather melancholy if not tragic stories as it turns out. And there is a great deal of attention given to Bernard Hall, including to questions not really connected with the main subject of the book.

It is certainly interesting to know more about these men who, with the partial exception of Hall, have been almost completely forgotten in the history of Australian art; such research is a valuable contribution to the revision of the story of the first half of the 20th century in particular, which has mostly been dominated by facile modernist narratives. As far as the shape of the book is concerned, however, several chapters constitute extended detours from what is ostensibly the main narrative, and for that reason the work ends up being more useful as a reference book to dip into than a story to read from beginning to end.

Curious editorial decisions exacerbate this problem, and indeed I can’t help feeling this would have been a much better book with more decisive editing. The big questions that I have alluded to above, and which set the scene for the main subject, should logically be introduced near the beginning, while in fact decorative painting and mural painting in the Arts and Crafts traditions are only discussed in chapters 18 and 19.

After that it would be natural to expect some discussion of the specific context in Australia, including precedents or concurrent projects, then a concise account of the competition and its outcome, followed by chapters on each of the contestants, ending with the winner and its reception.

More effective editing could also have spared us a stylistic mannerism that becomes increasingly irritating as we make our way through the text, namely the overuse of epithets: “extra-strong spectacle wearing Dancey” (p. 134) seems almost like self-parody; by page 153 the reader’s patience is wearing thin with “the well-connected Desbrowe Annear and Spencer were recompensed by the self-absorbed artist …” – at the end of a single page that is peppered with at least a dozen of these redundant formulas.

Nonetheless, there are many things to learn from Paffen’s book, the first of which, near the very beginning, is the fact, which I had not been aware of before, that the number of veterans who died of various causes in the decade after the Great War almost equalled those who actually perished in the conflict. This gives us a grim sense of the lingering after-effect of the war, effectively running like an underground stream beneath the superficial brightness and optimism of the 1920s.

There is, as one would expect, much good material on Australia’s war artists, as well as expatriate artists in general, and on problems relating to their return to Australia, including the imposition, after the war, of import duty on works of art brought into Australia. Expatriates were exempted if they had been abroad for five years or less – later extended to seven – but otherwise were no longer legally counted as Australian and were subject to the duty.

The question of the Australianness of expatriates comes up in a more subtle, but essentially parallel way in one of the most interesting and narratively satisfying sections of the book. This is devoted to another and in fact briefly more prominent mural project, for the decoration of the new Australia House building in London. King George V had laid the foundation stone in 1913 and eventually, in 1918, was able to declare it open.

From 1912, artists began to express interest in painting decorative murals for the new building. At first it seemed that the coterie of Australian artists already resident in London, and who congregated at the Chelsea Arts Club, would be ideally suited for the work: Streeton, Lambert and others were in discussion from the beginning. But then artists in Australia heard about the project and were alarmed to think they might be excluded.

The whole debate came to a premature end in 1915, when the question of commissioning paintings for Australia House was postponed indefinitely because of the war. By then Streeton, Bunny and Lambert had all executed studies for the project; their rivals at home, however, began to argue, much like the Customs Office, that they had been abroad too long. The spirit of Australian art, it was suggested, was elusive and did not survive transplantation from the colonies to London.

There is clearly some truth in this, when we compare Streeton’s brilliant work in Australia with the comparatively leaden pictures he painted in London, but it is interesting to see authentic provincial feeling being held up, in the newly independent Commonwealth, as more desirable than undifferentiated metropolitan competence.

For The Fallen: The 1921-1922 Melbourne Public Library Mural Competition within the setting of Decorative Painting in Australian Art by Paul Paffen (Australian Scholarly Publishing).

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout