Archibald portraits throughout history lighting up AGNSW

The centenary Archibald show at the Art Gallery of NSW celebrates the very best portraiture in Australian history.

Archibald 100, Art Gallery of NSW

Until September 26

If you are going to the Archibald this year, at least the ticket price includes an exhibition worth seeing, the survey of the first century of the prize. But instead of approaching this as an epilogue to the current show, I would advise visiting it first, for two reasons. The first is that you will be fresh and better able to appreciate the quality of the pictures; the second is that the shocking incoherence of the prize show itself will be even more apparent.

From more than 900 entries, as I have observed before, it would be easy to put together an exhibition of some 50 worthy pictures. Instead, the Trustees knowingly select a proverbial dog’s breakfast of the vulgar, the sensational, the dishonest and the incompetent, with a handful of real paintings, designed to excite precisely the kind of turbulent and emotional responses that one does not have when looking at good art of any kind. The Archibald is not a circus by accident, but by design.

The historical survey exhibition, on the other hand, was not assembled by businessmen and socialites, egged on by modish artists; it has been selected by Natalie Wilson, Curator of Australian and Pacific Art. The rubbish that is stuffed into the Archibald to excite the punters, provoke the chatter of journalists and make the bogans protest – often reasonably enough – that their five-year old could have done better, has almost all been omitted. The giant heads have disappeared. What remains, with a few exceptions, is what had, and still has merit.

So spend some time in the centenary exhibition first to calibrate your eye to what makes a good portrait – and there is a wide range of style and interpretation, not a single formula – and then inspect the prize exhibition where you should be able to distinguish at once the pictures that have any chance of appearing in a future historical survey from the dross destined for the landfill of art history.

Perhaps the first thing that is striking in this exhibition is the variety in style and approach to the sitter. Not everyone sees what is before their eyes, of course. Almost immediately after I entered the show, an elderly woman sourly asked two younger women what they could see. Clearly well-trained in the clichés of our day, they replied “portraits of men”, which the old culture warrior corrected to “middle-aged white men”. I was looking at Tempe Manning’s self-portrait as she spoke; but people like that don’t look, they simply parrot brainless slogans.

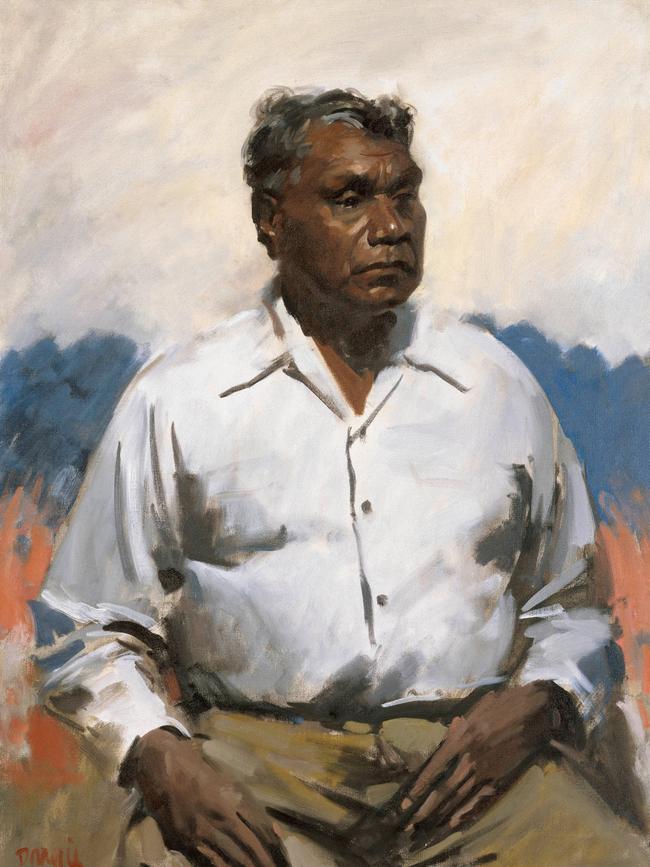

Speaking of which, one of the many controversies surrounding the Archibald was the protest by art students in 1952, when William Dargie won the prize for the seventh time with a strong portrait of Essington Lewis, chairman of BHP. A young John Olsen was quoted as declaring that “Dargie has nothing to do with art”. Four years later, Dargie’s direct, vivid and sympathetic portrait of Albert Namatjira won the prize again and became one of the most famous and memorable pictures in the history of the Archibald. Olsen himself won the prize in 2005 with Self-portrait Janus-faced, but if we compare the two pictures, he owes Dargie a posthumous apology.

Dargie had earlier won the Archibald with his powerful Corporal Jim Gordon VC (1942), but what the art students considered old-fashioned was the tonal realist style that had become the standard manner for portraits, especially those of eminent male subjects, most of whom were painted wearing dark suits, unless they had more picturesque uniforms or robes of office. But that was a generation with a shaky understanding of art history – they were still living in the modernist dream of throwing off the shackles of the past and starting all over again – and they clearly failed to realise that tonal realism was itself a modern way of painting.

The style arose from the rediscovery, by Manet, Whistler and others, of Velázquez and the Spanish masters of the 17th century as an alternative to the mainstream of post-renaissance classicism, which was at the time monopolised by the academic tradition. Early Australian exponents included George Lambert and Hugh Ramsay, both artists who have been recently celebrated in important exhibitions at the NGA. Significant women artists working in the same manner include Agnes Goodsir and Violet Teague.

Tonal realism became a staple of teaching at the National Gallery of Victoria school around the turn of the century, but it was fundamentally renewed by the teaching of Max Meldrum, who tried to make it into a quasi-scientific process. I explained part of his system a few months ago (Review, Saturday, March 27) in reviewing the beautiful Clarice Beckett exhibition in Adelaide, for Beckett was one of his most important and original pupils.

Meldrum’s method involved setting the canvas beside the motif – here the sitter – and trying to match the optical impression from a given distance, which in practice meant standing back to compare motif and image, then stepping forward to place a mark on the canvas, stepping back to compare the two, and so forth. I had the opportunity to watch Robert Hannaford paint a demonstration portrait in this way, and it was remarkable to see a striking likeness appear from a process that sought only to account for patches of light and shadow.

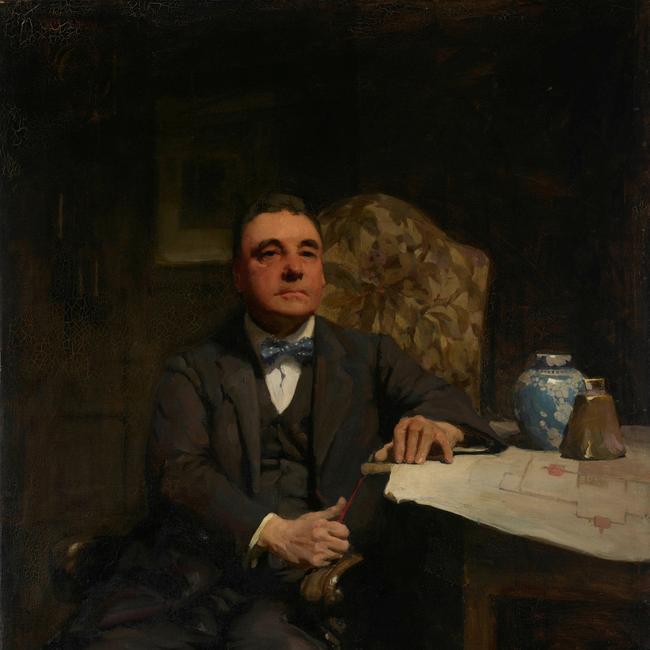

Meldrum’s influence is visible in many of the pictures in this exhibition, including in the very first winner of the prize, W.B. McInnes’ portrait of the architect Desbrow Annear (1921), Esther Paterson’s The Yellow gloves (1938) and Mary Cecil Allen’s picture of Hilda Elliott sitting in the artist’s studio (1925). One effect of Meldrum’s method is to produce a kind of vividly literal naturalism, akin to a photographic image, and yet characteristically blurred because of the distance from which it is painted: this is the effect we can see in the Chinese ginger jar in McInnes’ painting as well as the ceramics and other objects in Allen’s portrait.

Meldrum himself won the Archibald prize in 1939 and 1940, but the exhibition includes a characteristically provocative nearly nude self-portrait at the age of 75 (1949). The question that obviously comes to mind is how he could have produced such a picture following his own method, especially as it is an almost full-length, if seated, figure; he must, of course, have placed a mirror beside the canvas, but each time he got up to place a mark on the canvas he had to rely on a remarkable visual memory of the image he had seen in his reflection.

Many of the pictures hung in the Archibald prize over the years have been self-portraits. This sub-genre first arises in the renaissance, where 15th-century artists such as Masaccio, Ghiberti, Mantegna, Botticelli, Leonardo and many others often inserted a self-portrait into one of their important public works as a kind of signature. By the end of the century the self-portrait begins to appear as an independent picture, and with painters like Albrecht Duerer, it becomes a vehicle for self-examination as well as self-promotion.

As interest in the individual style and vision of artists grows in the 16th and 17th centuries, and as collectors begin to seek out the work of particular artists as a priority, self-portraits become increasingly popular, since they are at once an image of the artist and an example of the style. Nicolas Poussin’s two self-portraits were painted to complement important private collections of his work in Rome and in Paris. A little later, between 1664 and 1675, Cardinal Leopoldo de’ Medici formed a unique collection of 80 self-portraits which, now at the Uffizi, has since grown to 1630 pictures.

Probably because of its prominence and because it is one of the few art events that attracts the interest of the popular press and mass media, the prize has been surrounded by controversies, on several occasions ending up in court. One that is of uncomfortable relevance today is the disqualification of John Bloomfield’s portrait of Tim Burstall (1975), after it had been adjudged the winner, because it turned out that the artist had not met the sitter and had based his painting on a photograph.

A few years later (1981), Eric Smith won the prize for a portrait of Rudy Komon, one of the most prominent art dealers in Sydney at the time. When it emerged that the pose of the painting closely matched a photo, Bloomfield sued the Trustees. On this occasion the court found that Smith had made many studies of his subject, even if he had finally used the photo in coming up with the composition of the picture.

In retrospect however, Bloomfield could justifiably be disillusioned by the more recent blatant abuse of photography, even to the extent of painting over digitally-printed photographs, that has been tolerated in the past couple of decades. The eye-popping photorealism that impresses the uneducated mass audiences of this exhibition is all too often fraudulent.

The picture that benefited by Bloomfield’s disqualification was Kevin Connor’s portrait of his father-in-law Sir Frank Kitto (1975), who three decades earlier had represented the Trustees in the most notorious of all legal cases in the history of Australian art. When William Dobell won the prize in 1943 for his portrait of his friend and fellow-artist Joshua Smith, two other finalists, Mary Edwards and Joseph Wolinski, sued the Trustees, claiming that the work was a caricature rather than a real portrait.

The case came to court in 1943, with Garfield Barwick, later Chief Justice of the High Court, representing the plaintiffs. The case hinged, unfortunately, on whether Dobell had freakishly distorted Smith’s features or whether this was simply how he really looked. Needless to say this whole discussion was deeply hurtful to Smith, already sensitive about his appearance, and he never really recovered from the experience; but Dobell was almost equally traumatised and suffered extreme physical symptoms.

Interestingly, there is a self-portrait by Mary Edwards (her real name was Edwell-Burke) in the exhibition which, although not a great painting, reminds us that history, or the lazy and repeated retelling of legend, has turned her and Wolinski into caricatural figures in their turn.

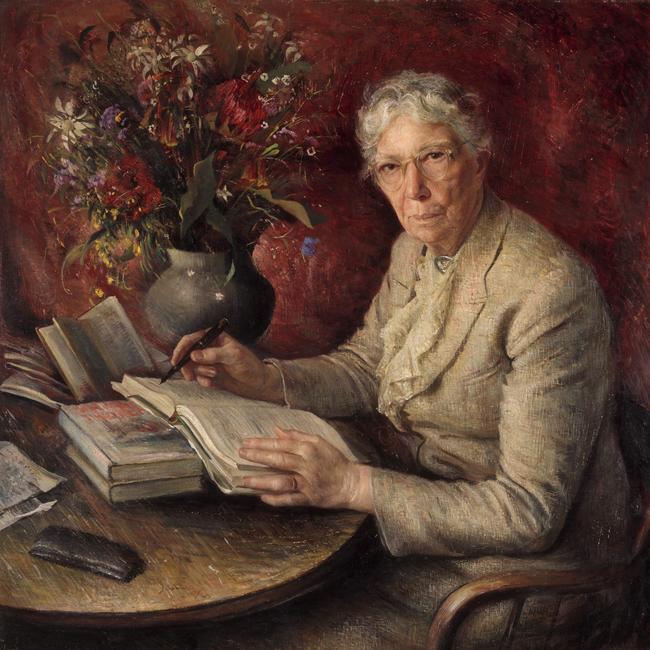

Among the other ironies of this story is the fact that, without Dobell’s portrait of him, Joshua Smith himself could have won the prize with a fine portrait of Dame Mary Gilmore. Smith was awarded the Archibald the following year but this felt like a consolation prize, especially because by then Dobell was himself a Trustee. And as for Mary Gilmore, it was once again Dobell who triumphed, with his remarkable, if strangely elongated, portrait of the poet in 1957. Smith would never equal Dobell but, as we can see, they are both among the artists to whom history grants a life beyond the transient sound and fury of the annual exhibition.