AGNSW’s Arthur Streeton survey is impressive

How two paintings by the prodigy, more than 30 years apart, show the evolution from the axe to the chainsaw and concerns about large-scale land-clearing.

One of the inevitable limitations of art-historical surveys of periods or movements is that individual artists end up being represented by a handful of works that are considered typical. This is not to deny the usefulness of such surveys, whether they take the form of a book or an exhibition or both. There is no other way to make sense of broad and collective cultural developments.

But the very idea of typical raises its own problems: do we mean typical of the artist or typical of the movement to which they happen to belong? And this in turn raises another question: especially in the last century and a half, the career of an artist tends to last much longer than a movement; all too often, we end up looking mostly at work produced during the period when the artist’s career coincided with a particular movement.

More subtly still, we often find that particularly significant artists can typify, even epitomise a movement or style without being reducible to it: thus Monet is the best example of Impressionism and Poussin of 17th century Classicism, and yet the work of each of these painters greatly exceeds any limited definition of their respective styles.

As Wayne Tunnicliffe’s impressive survey of the career of Arthur Streeton reminds us, all of these questions are applicable to this artist who was, with Tom Roberts, one of the two greatest painters of the Heidelberg School in the 1880s and 1890s, but who continued to paint important pictures for almost two generations after the heyday of that movement.

Streeton (1867-1943) did not live to be exceptionally old, but he started very young and was in fact something of a prodigy when we remember that he painted all of his most famous and perhaps most successful pictures in his twenties: Still Glides the Stream (1890) and Golden Summer (1890) at around 23; Fire’s On! (1891) around 24, and even The Purple Noon’s Transparent Might (1896) at about 29. It is no wonder that Roberts and McCubbin were impressed when they famously met the almost self-taught 19-year old painting on the beach at Mentone in 1886.

Roberts had just returned from Europe in 1885 and over the next couple of years, he and Streeton, along with Charles Conder, Frederick McCubbin and some lesser figures, articulated a style of painting which spoke of a new sense of intimacy with Australian landscape. In the earliest phase of settlement, Australian nature was an object first of scientific curiosity, and then of picturesque appreciation. In the high colonial period, Eugene von Guerard and other artists began to come to terms with Australia as a permanent home, and sought to represent its grandeur, antiquity and mysterious, unfamiliar character.

Abram Louis Buvelot however, the only painter that Roberts and Streeton considered a true precursor, had shifted his focus from wild and sublime spectacles like mountains to the more modest and familiar motifs of settled farmland and pastures. He approached these motifs, too, through the correspondingly intimate and informal means of plein-air painting. The Heidelberg painters continued in this vein, camping out in the countryside and painting together, evolving a new vision of confident dwelling in the Australian landscape.

This initial phase culminated in a summer of painting at a friend’s farm at Eaglemont in 1888-89, coinciding with the centenary of the settlement of Sydney, which naturally contributed to a growing national self-consciousness and accelerated the movement towards the federation of the colonies. Roberts and Streeton began to look at the Australian environment with new eyes, but as I argued long ago, this was not just a matter of paying attention to the shape of the gum tree and noticing the glare of the Australian light.

Work was an important theme, as we can see in Roberts’s Charcoal Burners (1886) or Shearing the Rams (1890), and in Streeton’s The Selector’s Hut (1890); labour was what established the moral legitimacy of our presence in this land, and I would suggest that it is that moral adjustment, more than anything else, which allowed them to see the flora of Australia in a new way and drew them to concentrate on the heat and glare, in turn leading to a heightening of their landscape palette.

Hot, bright pictures painted in midday sun in summer, in a very high key, have come to be considered the quintessential expression of the Heidelberg school, and yet even a casual glance at this exhibition reveals that only a certain proportion of Streeton’s pictures represent such conditions. Perhaps the most surprising thing is that almost all of the beautiful little oil studies that he did for the group’s historic 9 x 5 Exhibition in 1889 are evenings or nocturnes, with little or no bright light in evidence.

On the other hand, there are several pictures which were not only clearly painted in the midday sun and the brightest possible conditions, but whose very titles emphasise this fact. This is all the more interesting when we consider that almost anyone who wrote about this question advised against painting at midday, when the universal brightness flattens forms, reduces shadows and strips away any kind of atmospheric effect or mood.

Streeton did not paint these midday scenes because he was unaware of the more appealing character of morning and afternoon light, as many other pictures make very clear. To paint in the midday light was difficult and on the face of it unrewarding; but Streeton must have intuitively felt that this was a trial the Australian painter had to face if he was truly to prove himself equal to the natural conditions of this land. It was, for the artist, a challenge parallel to that of the farmer in cultivating the poor, arid soil.

In this sense, we can indeed see how some of Streeton’s landscapes epitomise the vision of Heidelberg, and yet, returning to the principle I cited earlier, he cannot be reduced to the movement of which he is, with Roberts, the pre-eminent exponent. A way to understand this is suggested by one of the most interesting pairings in the exhibition, that of The Selector’s Hut with Above us the Great Grave Sky, painted in the same year, and which shows a couple lying on a grassy bank watching the rising moon.

The first of these pictures, in other words, is programmatic and represents a public and ultimately political vision, bright, strong and optimistic in tone. The second is concerned with personal, private and even romantic experience. The first represents what we think of as the very spirit of Heidelberg and its distinctive vision, but the second is also a part of Streeton’s sensibility and can be compared with other works by Roberts, Conder and McCubbin.

The other great question with Streeton, and which this exhibition inevitably raises because of its monographic character, concerns the evolution of his style. On his way to England in 1897, he stopped in Cairo, where he painted some pictures that are full of the excitement of discovering a new and exotic world. But the pictures painted in England become quite suddenly heavy and joyless, even when he seems to be looking at the examples of artists whose own work was anything but heavy, like Turner and Whistler.

This is not just due to the depressing effect of English weather or even of subjects to which he was not attuned in the same way that he was to his Australian motifs, for the problem persists even on his brief return to Australia in 1906-07. His style has lost all its lively freshness; painterliness and calligraphic gestural marks are banished, and the palette has become dour and drab.

The application of paint is coarse and chunky too, and the paint itself is opaque, matte, dry and chalky. In his earlier work, for example in Fire’s On!, shadow areas are often represented by translucent brown underpainting, over which opaque paint is applied fluidly and confidently for the lit areas: this traditional approach is economical, makes the illuminated elements stand out more effectively while letting the shadows drop away without explicit emphasis, and imbues the whole paint surface with freshness and animation.

Now, in contrast — like a plodding author who leaves nothing to the imagination and intelligence of the reader — everything is painted in heavy opaque paint, even the shadows, which are thick black instead of the more self-effacing translucent brown; the result is darks that are more emphatic and yet less effective in suggesting depth. One can only attribute this change to the unfortunate effect of contemporary British painting — the effect makes one think of Sickert but does not transfer well from Sickert’s figure subjects to landscape — and perhaps to some odd impulse to paint in a more masculine and assertive way.

Nonetheless the pictures sold well in Australia, allowing Streeton to marry at last. On his honeymoon in Venice with his wife Nora, he had a burst of exuberant productivity, but his work as a war artist is a more important part of his oeuvre, because it gave him a new sense of motivation and purpose. After the war he eventually settled back in Australia in 1923, and there at last he begins to re-acclimatise to the Australian environment from which he had seemed so alienated in Britain.

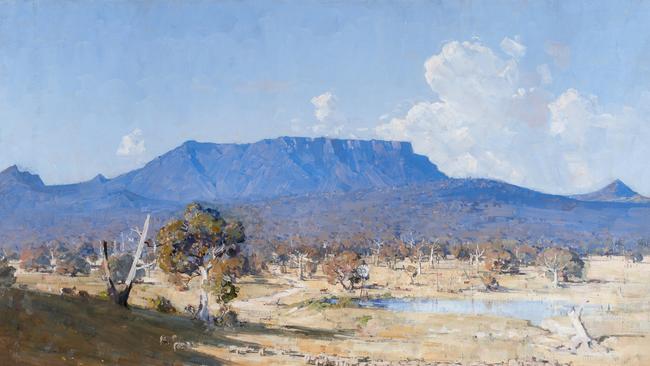

He never fully regained the lightness and freshness of the painting of his youth, although we glimpse something of that vitality in The Creek (1925), which stands out among the late pictures. Even The Land of the Golden Fleece (1926), the most impressive of his late landscapes and a painting in which he revisits his earlier blue and gold palette, remains relatively heavily painted and subdued in colour.

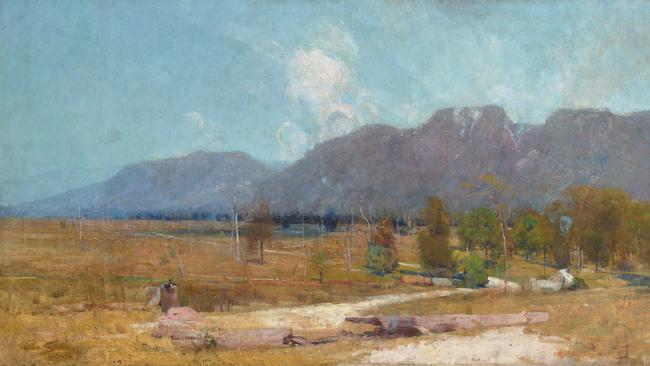

Streeton’s most interesting late pictures are the evidently deeply felt paintings that evoke the excesses of land-clearing. In one of these we simply see a great tree felled and cut into huge rounds. In another there is a little man cutting up a fallen log with a gasoline-powered chainsaw, a new invention of the 1920s. Forest clearing had already done much damage, but with mechanised tools the destruction accelerated rapidly and catastrophically.

These paintings are all the more poignant when we consider the symbolism of the axe in The Selector’s Hut, three and half decades earlier — the image of a man resting and smoking after working to cut up a fallen tree. This was a celebration of the honest labour of a modest selector, making a life for himself and his family, and implicitly helping to build a nation.

The later picture shows the anonymous employee of a corporation, hired for wages and cutting down forests for private gain that is ultimately prejudicial to the good of the nation. In each case, however, it is the sense of moral seriousness that endows Streeton’s image with sharp and memorable focus.

Arthur Streeton, Art Gallery of NSW, until February 14.