Academic Kylie Moore-Gilbert relives Iran jail terror

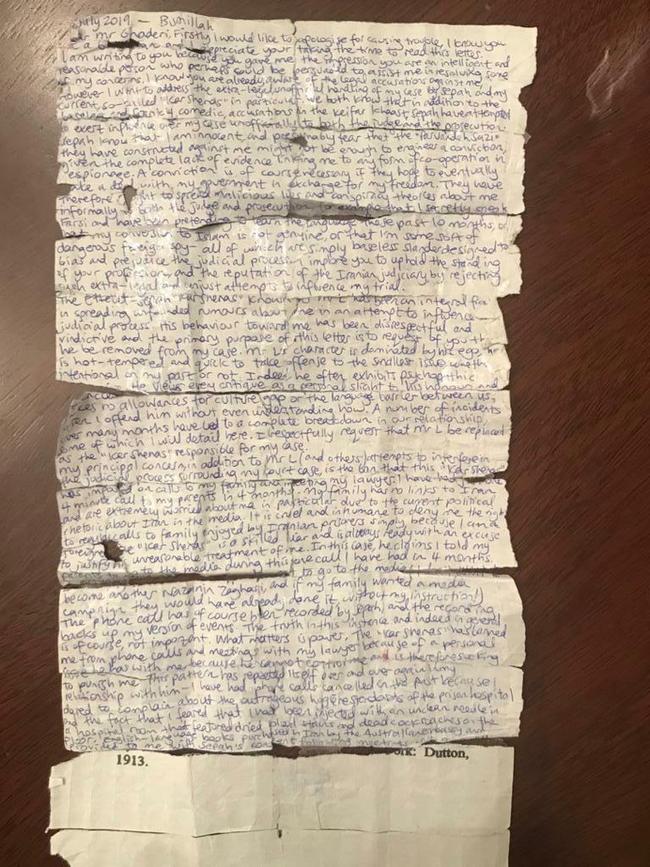

Psychological torture is how Melbourne woman Kylie Moore-Gilbert describes her 804 days in prison in Iran.

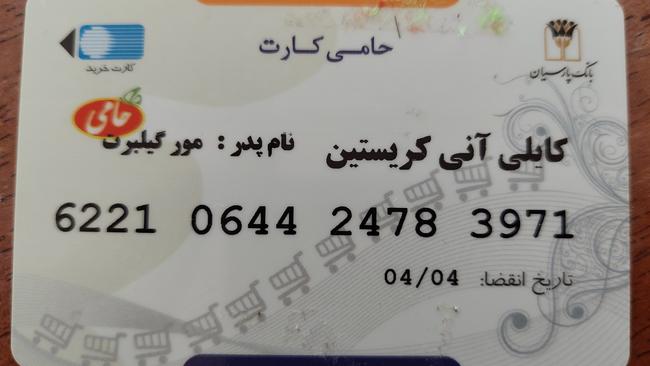

Kylie Moore-Gilbert was a 31-year-old junior academic when she was arrested on trumped-up charges in Iran.

It was September 2018. She would go on to spend 804 days in prison. From the first, sleepless nights and days, she was in torment: she had no idea when, if ever, she would be free; whether it would be two days, or 10 years, or longer; whether she would still be young enough to have a child, whether she would ever see her family, or taste her freedom, again.

She desperately needed assistance - she had done nothing wrong and yet was sitting blindfolded, behind bars, at the mercy of an unfamiliar legal system - and yet, for at least the first year, there was no public outcry in Australia, no media pressure, no human rights campaign, no strong statement from the federal government, the opposition, or academia.

It is terrible to have to listen as Moore-Gilbert, now home in Melbourne, explains how that was for her.

“In the beginning, I didn’t feel like I had anyone in my corner,” she says.

“There were some people on the internet – a lady from Toowoomba, a bloke from Castlemaine, and a complete stranger in Wales – who started a Change.org petition, and I’m so grateful to them now, but I didn’t find out about that until later.

“I felt very alone.”

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade warned Moore-Gilbert’s family against making a fuss in the media, apparently believing that quiet diplomacy would do the trick.

When it didn’t, some of Moore-Gilbert’s friends from Curtin, ANU and Deakin University tried to help, but the media had been warned by DFAT not to get involved in case she ended up being punished.

And so it makes perfect sense that when Ian Biggs, the first of two ambassadors with whom she dealt, finally went to see her, she threw her arms around his legs and wouldn’t let go.

“I just needed to know somebody was with me,” she says.

She demanded to know what was being done to free her, and was told: “We are pursuing all avenues … we are liaising with the relevant authorities …”

“I don’t think they had any idea what to do,” she says, with her delicate hand on the coffee cup between us. “The Iranians told me they had been trying to Google the Australians, trying to get in touch, because nobody was reaching out to them.

“They couldn’t believe how little attention was being paid to me.”

The University of Melbourne, where Moore-Gilbert had been employed when she took her trip, made no bold statements about academic freedom, and there was no campaign by the university to highlight the importance of scholars being allowed to travel, safely and securely, as they seek to make connections and share knowledge across the globe.

Some fellow academics actually decided to make things worse for Moore-Gilbert by making sly remarks on social media, hinting that she might have been a spy because her former husband was Israeli.

“It’s ridiculous,” she says. “You need a certain level of sophistication and intelligence to be a spy. He does not have it. He was in his 20s when I met him, and he came to Australia with me.

“He’s not a spy. I’m not a spy. I was a junior academic, doing what thousands of academics do every year, travelling for a conference, and I was arrested (and accused of spying).”

Without anyone in her corner, Moore-Gilbert sat, and waited, and got sentenced to 10 years in prison, and only got out after a new ambassador, Lyndall Sachs – “tiny, but fierce” – was appointed and took over the negotiations necessary to have her set free.

Moore-Gilbert has now written a book, The Uncaged Sky (Ultimo Press), about her experience. Like many people, I was curious about her time behind bars in the notorious Evin prison, but also about her former husband, since it is well-known that he didn’t stand by her in her hour of need, running off with her friend – indeed, with her Ph.D supervisor – while she was in prison.

How does she deal with this in the book?

With grace, is the answer.

She deals with it calmly, and cleanly.

“The book isn’t about him,” she says. “I couldn’t focus on him while I was in prison. I had to focus on getting through. He had checked out while I was still in there, but if he didn’t want to be married to me anymore, well, I didn’t want to be married to him either.”

She has moved on. There is a new chap in her life who is far more supportive.

As for the rest of the book, it reads like an espionage thriller: She’s at the hotel when the police come for her. She is questioned and then allowed to roam in Tehran while they decide what to do with her. She thinks about going to the Australian embassy, but she doesn’t know where it is.

She doesn’t have a phone; they’ve taken it. She tries Googling the embassy, but there is no address and no phone number on the website (that’s now changed.) She thinks now that she probably could have convinced a sympathetic local to help her by tapping her on the shoulder, saying something like, “can I borrow your phone, can you look up the embassy address for me, I’m a bit lost …”.

“But I wasn’t thinking clearly,” she says. She also didn’t, for a moment, believe that she was headed to prison for 10 years.

“The Australian government knows that I am not a spy. Obviously they know that,” she says. “They share intelligence with allies – the so-called Five Eyes. If they thought I was a spy for Israel, they could ring up and ask them, and Israel would have said, no, we’ve never heard of her.

“I believed they’d do that, and then help get me out.”

Instead, there was almost no communication.

“It’s hard to describe, spending 23 hours a day in a small cell, staring at the wall, nothing to look at, nothing to read, nothing to do, it’s psychological torture,” she says.

At one point, her captors told her to tell her then-husband to travel to Iran, and she told them no, since she knew he’d never agree to take her place in a prison cell.

“Anyway, they wouldn’t have released me,” she says. “They would have picked him up as well, and we both would have been stuck there. Which is why I told him not to come. To save him that.”

She recalls the moment she heard that another Australian woman, a travel blogger, Jolie King, had arrived at the prison, having been arrested for flying a drone over the desert.

She rushed to comfort her.

“She was completely distraught,” she says. But that case quickly made the news, and King was out in a matter of months, free to resume her travels with her boyfriend, which she promptly did.

Moore-Gilbert remained trapped. She has a restless, inquiring mind and decided that she would teach herself Farsi, asking for an English-Farsi dictionary and comparing the words to the words in the Iranian newspaper made available to prisoners.

By the end of her time there, she could read it cover-to-cover.

She found only one news story about Australia in the two years: “A boy who threw an egg at a politician?”

Egg boy! He made it big in Iran?

“He did,” she laughs. “A small item. The only thing about Australia that I saw.”

Certainly, there was nothing about her plight, and the guards taunted her, saying: “Nobody is coming for you.”

They did come, in the end.

Moore-Gilbert says Sachs – a senior career officer, and former chief of protocol – “got me out”. There was a complicated, four-way prisoner swap, about which she knows little. She was flown to Canberra and, in a very Australian move, put straight in hotel quarantine. She can laugh about it now.

“I had a bed,” she said. “I had the internet! It was fine.”

Still young at 34, Moore-Gilbert says she is hopeful about the future. Well-educated, intelligent and beautiful, with glossy hair and a shy smile, she has a home in the bush outside Melbourne and hopes to get a dog one day. She is unemployed, but not particularly troubled.

“Obviously my life changed,” she said, of coming home. “I was a newly-married woman, an academic, when I went to prison. I lost my marriage. I lost my career.”

But she’d written a book in her head, and was keen to get it on paper. That is now done, and the next few months will be a busy round of interviews and festivals. And after that?

“People keep asking me, what are you going to do?” she says. “I’m going to have to come up with an answer.”

There were some things she missed, and desperately wanted: a good supply of real coffee, avocadoes, a Western toilet, a pillow. She has them. The rest can wait.

Kylie Moore-Gilbert will appear at the Sydney Writers’ Festival, and the Brisbane Writers Festival. The Uncaged Sky (Ultimo Press) is out now.