A world tour in the time of Covid

Ken Haley was due to take a long holiday in 2020, seeing the world in his wheelchair. Then came Covid. Despite the uncertainty, off he went anyway.

Decades ago I decided that seeing the world was more important to me than owning the roof over my head. Every few years, using the money saved from not saddling myself with a mortgage, I take myself off to a previously unvisited part of the globe, and explore its constituent nations, cities, towns and islands in depth.

In 2020, four years after crossing Canada and three-quarters of the US, my eyes were focused on the Caribbean and Central America.

Weeks were spent crafting an itinerary covering 21 countries in two stages: from Cuba to Trinidad; then for the final three of 12 months away I’d be southward bound from Mexico to Panama.

A grand plan, in every sense, but far from the most ambitious I had carried out.

While I disdain the label “tourist” – I’d rather meet people than ogle landmarks – I pencilled in a slew of tourist destinations, including Montego Bay and Santo Domingo’s cathedral (the western hemisphere’s oldest).

Organising a journey in advance whets my appetite for the real thing. For me, filling a travel diary with things to do and see no more spoils the spontaneity than preparing a well-researched travel budget turns me into an accountant.

January 2020 found me in mid-preparation – ticking off typhoid and yellow-fever vaccinations – when the media first carried word of a fast-spreading plague that had shut down Wuhan, China.

By February – the month I was due to be off – it was causing hospital admissions in Thailand and Italy. But travel agencies were still fully staffed (my local one had just arranged my first flight trifecta, to Canada, Cuba and Jamaica) and borders both here and abroad were open.

Over the horizon, I recall thinking, this might get much worse. But not a single Covid fatality had been reported where I was headed. “Quarantine” conjured up what operators of the Ruby Princess could be expected to look after – not yet a word associated with hotels.

I’m used to travelling solo. This year, wherever I went, I would have company: Covid was either in my slipstream or had already arrived at my next destination.

Awareness of this first surfaced on March 14, as I threw open the jalousied colonial doors of my bedroom at the Hostal Florida Terrace in Santa Clara, Cuba, and saw two uniformed nurses at reception clutching mouth thermometers and clipboards. Within a minute (mostly) carefree travel had become testing.

Back then, mask wearing was the exception; transport was running; museums, restaurants and cafés remained open. The knell struck a week later, upon arrival in south-coastal Trinidad de Cuba.

The bus terminal manager, called in on a Sunday, addressed two dozen foreigners in the forecourt: “The Government has announced … that all foreign travellers now in Cuba must leave within 48 hours.” That day, all coaches (if not roads) led to Havana.

The Great Fear had already descended. The boisterous Old Havana of just a week ago now resembled a ghost town: of seven restaurants flanking an alley in the heart of the historical quarter, only one was still trading.

Next morning, for the first time in my life I found myself heading to an airport not knowing where I would fetch up that night – if I could catch a flight at all. My precious plan appeared derailed rather than wrecked: after all, I’d completed 22 of the 26 days allotted for Cuba.

Shouldn’t I go home? Hold your nerve, I told myself. Having invested so much energy and money on this far-flung expedition, I was loath to kiss goodbye to the tropics on such brief acquaintance. Wait a while and see if the Caribbean gets back to business.

After seven hours I secured the last seat available on what proved to be one of the final two commercial flights before the deadline.

The Immigration officer in Fort Lauderdale could have given me marching orders but issued a six-month visa instead.

During those anxious weeks I churned through 15 changes of plan; obtained refunds on a dozen unusable airfares. Countless hours were spent on the phone to airline clerks, making or cancelling bookings, hostage to phantom “reopening dates”.

As June rolled around, my gamble paid off. I was free again to travel, and I had somehow escaped the trauma that millions of home-bound Victorians were undergoing.

Of course, my viral fellow traveller was also in the air. First contact on airport arrival was no longer an immigration officer demanding my passport but often a PPE-clad nurse proffering a rapid-antigen test device.

Every border crossing now required advance compliance with its latest entry criteria (which, infuriatingly, would often change overnight – and, in the case of Dominica, mid-flight!). Having been advised that a pre-flight negative test result would be acceptable, upon disembarking, we were all bussed to an evacuated medical college that posed a greater health hazard than any of us were likely to inflict.

The mosquito-ridden site bordered a stagnant pond. The Dominicans solemnly informed us that it was also a likely breeding ground for Zika and dengue fever. Recent outbreaks of both had probed fatal.

At one point, armed police trooped on to the property, assembled us downstairs and read out the local version of the Riot Act, in case we had planned to escape. Fear was palpable on every face. In five months of continuous island hopping, this was the moment that felt least like being on holiday.

It was nowhere near as scary when a sneak thief in Saint Lucia spirited my wallet from deep in my backpack, so niftily that I didn’t discover it was missing until much later. The robbery wasn’t caused by the fact that being a wheelchair user makes you more vulnerable than other travellers in some respects, but perhaps it made the misadventure more likely?

I tried the local constabulary and when they went AWOL, I called in The Media! A TV crew came out to interview me, and the clip attracted 30,000 “likes” on the station’s online platform (20 per cent of the national population).

Comments on the accompanying video post ranged from shame at this attack on a foreign visitor to amazement that “at such a time as this” there actually was a foreign visitor.

Only now do I realise that behind many of the friendly smiles I encountered there must have lurked a deep unease. After all, for every country but China, Covid has been an imported scourge. How could they know where I’d been?

In the end I came home only two months early.

Ten months on, living through more than half of Melbourne’s total lockdown time has given me a keen appreciation of the knock to morale inflicted by months of confinement.

Despite my year of travelling precariously, the risks I took now seem to me to have been worth it.

The calculus is compelling. Unlike others, I saw a lot of the world in 2020, and none of it through a Zoom screen.

-

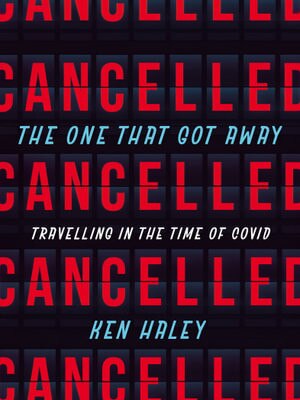

The One That Got Away: Travelling in the Time of Covid

By Ken Haley

Transit Lounge, $32.99, published November 1