A radiant exhibition, Light: Works from the Tate’s Collection, ACMI

Light has come to symbolise the beginning of life, clarity of reason and a feeling of joy. We don’t call a rainy day gloomy for nothing.

All creatures respond to light, which even in the age of electricity still overwhelmingly means the light of the sun. The artificial light we use in our homes, offices and factories mostly relies on fossilised energy that originally shone down on to our planet millions of years ago.

Plants respond to light and grow towards it, reaching out from under eaves or the shadow of bigger trees; some plants, such as sunflowers, move daily to face the sun. There are numerous stories about animals and the sun: bears know when it is spring and time to stop hibernating when they venture to the mouth of their cave and find their own shadow cast on the ground before them.

Humans, of course, have always been preoccupied with light and with the sun. In early cultures and religious beliefs, rituals were carried out to ensure the rising of the sun every morning as well as its annual return to life-giving warmth in the spring. Everything is magical in these cultures and nothing is supernatural, because the conception of nature and its laws does not yet exist.

Beyond such anxieties, light has countless layers of symbolism: in ancient literature it is associated with life itself, since the underworld is imagined as a place of darkness. But even in the pagan underworld the blessed and the initiates enjoy light, and all religions that have an idea of heaven imagine it as luminous – like the heavenly effulgence that fills Baroque ceilings and domes.

Light can also symbolise the clarity of reason, compared with the darkness of superstition, fear and violence; or it can stand for the quality of spiritual insight that dispels the gloom of the ego and its self-centred desires and fears. In both cases the word enlightenment is used, with different connotations for rationalist philosophers and for seekers after wisdom or the spiritual.

And, even more viscerally, light is joy. We don’t call a rainy day gloomy for nothing. No one, it seems, can resist the feeling of relief when the sun comes out, or of sudden delight when we see the most banal city building illuminated by the evening sun.

Just before seeing the exhibition at ACMI, I arrived in Melbourne on a Saturday so miserable that it felt like night in the midafternoon. On the following morning, the sky was blue and the sun almost hot. A city which had felt funereal was suddenly happy and alive.

This exhibition from the Tate collection in Britain deals with the representation of light in art across a period of more than 200 years, from the Romantic period to the present. It begins, like God, with the creation of light. It is not quite right to say, as the wall panel asserts, that light was the first thing that God created in Genesis. Strictly speaking, he created Heaven and Earth, but earth was without form and void, so the creation of light, and its subsequent division from darkness, was the first step in giving our world any kind of shape. Nothing is declared good or beautiful before the creation of light.

Several of the artists in the first section of the exhibition seem particularly concerned with light in relation to the later story of the flood. When God decides to destroy the world, it is of course grey and gloomy; when the flood waters recede, the light returns.

A subsequent section is devoted to the scientific understanding of light as represented by artists. The room is dominated by Turner, who in one pair of pictures attempts to illustrate Goethe’s theory of colours – which in its most simplified version deals with the happiness of warm colours and the melancholy of cool colours. Next to these is another Turner which epitomises the way he eliminated the element of earth from his landscapes to concentrate on the alchemy of fire and water.

The next part is ostensibly devoted to the sublime, although Turner is about as sublime as it gets, and the pictures in this room could also be associated with scientific reflections on the phenomena of light. Most notable are the paintings of Joseph Wright of Derby, who was fascinated by the contrast of warm and cool light: in one picture, a view of the Tuscan coast, he sets the warm glow of a lighthouse against the icy light of the moon.

In another and more ambitious painting, Wright paints an apocalyptic eruption of Vesuvius, contrasted with the silvery luminescence of the full moon on the Bay of Naples. The furnace-hot light of the volcano is a demonstration of the way that such an intense impression of light can only be achieved in painting by a combination of contrasting darks and subtle steps in the hot and bright pigments. In contrast, John Martin’s imaginary view of Vesuvius erupting in 79 and destroying Pompeii and Herculaneum is almost suffocating in its unrelieved heat and visual rhetoric.

The sublime was the experience, first described by Edmund Burke in 1757, of the overwhelming grandeur of nature: it was the vertiginous sensation of excitement mixed with terror that we feel before such phenomena as great storms, Alpine wastelands or volcanic eruptions. A gentler Romantic experience of everyday nature is evoked in the following room, especially represented by John Constable.

The first of two Constables hanging side-by-side is a quiet seaside view with a low horizon in the Dutch manner, whose composition is given definition by the shadow, in the foreground, of an unseen cloud above; such transient shadows cast by clouds were called accidents of light in early landscape theory. The immediate foreground is sunlit and includes a boy who inevitably (as Jeffrey Smart never tired of pointing out) forms a compositional focus, reinforced chromatically by his red bonnet, the only touch of red in the painting.

The second Constable painting is more obviously Romantic, including darker clouds in the sky as well as a view over Hampstead Heath with a low-key version of the Ruckenfigur – a figure seen from the back who prompts the viewer to admire the view – in the form of a boy sitting on a hill, again drawing our attention with his red waistcoat.

Constable is also represented by an important series of prints executed by David Lucas. The publication of paintings in the form of prints had begun in the high Renaissance three centuries earlier, but engraving in particular was more suited to figure subjects. While there were landscape prints from the 16th century – and notably the landscape etchings of Rembrandt in the 17th – there was little thought of reproducing painted landscapes before the 18th century. It was the relatively new technique of mezzotint that made it possible to capture the kind of subtle atmospheric effects that were essential to the painting of nature.

Tone can be achieved in engraving, etching and drypoint through hatching, and in aquatint by creating large but separate areas of tone, but only mezzotint permits a continuous range of tone like that of a photograph, although the technique antedates photography by almost two centuries.

In mezzotint, a copper plate is prepared with a device called a rocker, which covers it in millions of tiny pits. When inked, wiped and printed, such a plate should print a uniform black surface. From this point, the plate is scraped back, removing the pits, to create successively lighter areas of tone. Where all the pits are removed, the plate will print white, hence the continuous gradient of tone that can be achieved by a master printer.

After Constable, Monet represents another stage in the spontaneous response to natural effects en plein air and before the motif. There is an interesting contrast between a picture of his that is a dawn study of a river and an adjacent painting by the British artist John Brett, also very fine but composed in the studio from studies and notes made on location. One particularly spontaneous plein-air work appears not to have been retouched in the studio at all: a record of young poplars fringing a river, and whose curving line in the background implies the winding course of the stream.

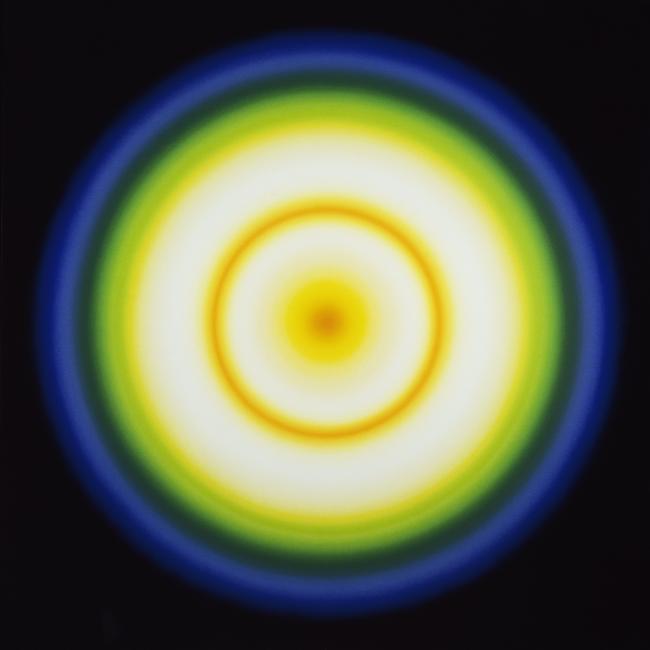

The later modernist and contemporary periods are represented by a number of photographic and painterly works, but the most interesting pieces belong to the past half-century, beginning with an optical piece by Peter Sedgley from 1970, and ending with a film work by Tacita Dean which alternates images of the inside of a lighthouse, with an ocean view just visible beyond, and the slow setting of the sun over the ocean. Through all of this the artifice is emphasised by the sound and light of the projector that shows the film on a loop.

Two of the most impressive works in this final section are by Olafur Eliasson and James Turrell. Turrell’s is a room filled with low but intense blue light, undifferentiated but for an oblong panel on the far wall. The environment almost abolishes the sense of space and therefore of time. The visitor floats in a completely neutral environment stripped of any of the references that orient our sense of self.

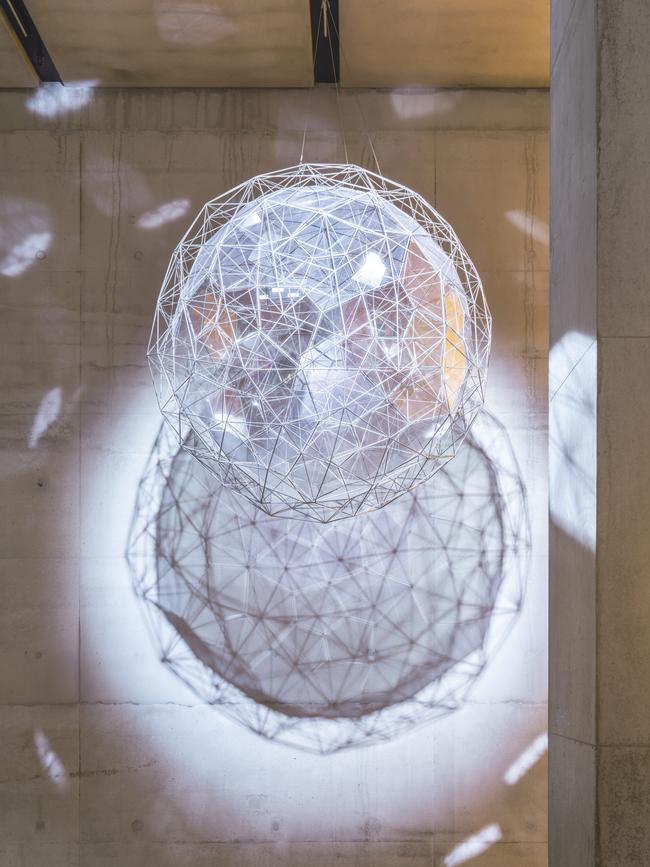

If Turrell’s work dissolves the world of the self by a kind of sensory deprivation, Eliasson’s dwarfs the individual – as he did some years ago in his solar installation at Tate Modern – in the contemplation of cosmic phenomena. A darkened space is dominated by a vast and slowly moving sphere, made of a translucent material and illuminated by a spotlight so that its form is projected on to the wall behind.

The spherical body naturally makes us think of a moon or star, and it turns out that its form is based on the structure of a particle of stardust. The facets of the sphere are reflective as well as translucent, so that patches of light are reflected over the walls and floor of the room in a slowly changing pattern, animating the space and involving the viewer in a way that a static object could not.

Both of these works evoke a kind of wonder and suggest, in different ways, dimensions of awareness beyond the egoistic, busy and trivial world of our everyday preoccupations. They are also, however, typical of many contemporary installations in being conceived as so-called immersive experiences that place the visitor in an essentially passive position. The paintings in the earlier part of the exhibition demand a much more active engagement if the viewer is to enter into them and truly see them – a different kind of energy and attention which seems increasingly foreign to audiences trained in passive immersion.

Light: Works from the Tate’s Collection, ACMI, Melbourne to November 13.

Story of the Moving Image

Australian Centre for the Moving Image

New permanent exhibition

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout