A famous Italian murder case is the latest in the fascinating true crime genre

When investigators found unknown DNA on 13-year-old Yara Gambirasio remains, it lead them to undertake the country’s largest DNA sweep. Did they close in on the wrong man?

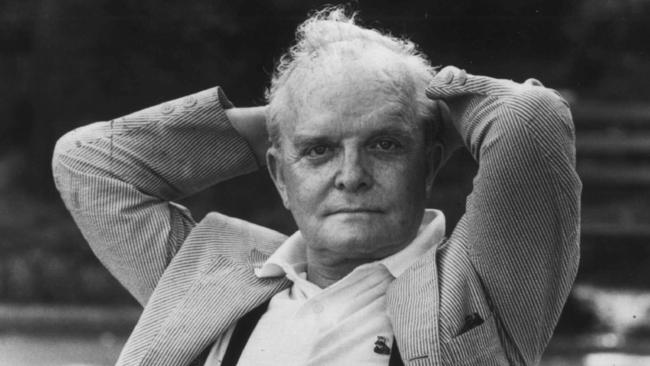

It’s often assumed that true crime originated with Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, published in 1965, in which the writer created the “non-fiction novel”, making him a celebrity.

But our obsession with true stories about murder, brutality and malfeasance, and our love of gorging on them, or being pleasurably disturbed by them, goes back as far as the Renaissance. Then broadsheets and pamphlets were circulated of those condemned to death, often sold around executions.

A couple of hundred years later, we see the hugely successful pulp-fiction novels and magazines featuring true crimes, later superseded by sensationalist pulp fiction magazines such as True Detective.

There’s the early work too of Errol Morris with 1988’s The Thin Blue Line, and Joe Berlinger, now a Netflix staple, who with Bruce Sinofsky created the Paradise Lost trilogy and Brother’s Keeper. But back then, as Berlinger told The Ringer: “We used to be the bastard stepchildren of the entertainment industry, knocking on the door saying, ‘Hey, we tell interesting stories, too, and please let us in’.”

And with TV let us not forget the inimitable Dominick Dunne and his hugely successful Dominick Dunne’s Power, Privilege and Justice, which began in 2002 exploring the mysterious real-life cases of greed, mendacity, betrayal, financial perfidy, sexual disloyalty and murder lurking inside the mansions of some of the world’s richest homes.

Then, following the extraordinary success of both Netflix’s Making a Murderer HBO’s The Jinx, both of which emerged in 2015, the genre expanded, while Sarah Koenig’s innovative podcast 2014 Serial – with its propulsive storytelling, and the discussion it provoked around civil rights – spawned a flourishing cottage industry built around true crime stories.

Netflix saw a cultural moment evolving and the true crime documentary genre became the fastest-growing segment of the streaming industry, with the streamer churning out so-called “prestige” true crime shows seemingly about one a month. And the genre has grown significantly, with a highly cinematic approach to content, storytelling techniques and prestige providing a kind of comfort.

“Focusing on one case, bearing down on its minutiae and discovering who is to blame, serves as both an escape and a means of feeling in control, giving us an area where justice is possible,” argues Alice Bolin in her influential essay, “The Ethical Dilemma of Highbrow True Crime”.

The latest is The Yara Gambirasio Case: Beyond Reasonable Doubt from new Milan-based production company Quarantadue, calling itself a “creative factory”. Two of its objectives are quoted on its website, “We don’t do cheap” and “We don’t play safe”. The Yara Gambirasio Case is directed by the company’s creative director, Gianluca Neri, a screenwriter who seems to have specialised in creating new media formats and is also one of the writers of the five-part series. And it wasn’t cheap, and it takes some risks, too.

Neri’s docuseries retraces, in intense, sometimes perplexing detail, the story of Yara Gambirasio, a 13-year-old from Brembate di Sopra, a pretty Italian town huddled in the picturesque Lombardy region, who disappeared on November 26, 2010. That night, she’d last been seen not far from her home at the gym where she practised rhythmic gymnastics, preparing for her display the following Sunday.

The story starts with moving amateur footage of her performing and her father’s voiceover: “She was just a cheerful child; she’s wearing a huge smile on her face with her teeth covered by braces.” And as the days vanish in a cloud of apprehension and dread, Yara’s family find itself at the centre of a mystery that captures the country’s imagination.

Neri uses the media’s obsession with crime to provide the narrative links in the story, obviating the need for a conventional narrator. And a colourful, assertive and opinionated bunch of commentators they are too, determined to ensure the protection of their own standing.

After three months of extensive searches involving tracker dogs and heavy press coverage, the girl’s body is found in a nearby field. It’s discovered by a middle-aged man named Ilario Scotti flying his radio-controlled plane in the small town of Chignolo d’Isola, just south of Brembate di Sopra. She hadn’t been raped, though she was stabbed, and it appeared she had died from exposure.

When investigators find unknown DNA on her remains, it leads them to undertake the country’s largest DNA sweep, a highly controversial procedure, as they search for the killer, they name Ignoto 1 – “Unknown 1”.

On June 16, 2014, Massimo Giuseppe Bossetti, an Italian bricklayer and father of three, oddly an inveterate suntanner, who lives and works in the area, is arrested and accused of being the murderer, mainly by virtue of his DNA matching.

The intrusive process eventually unearths controversial family secrets that eventually have Bossetti’s supporters and legal team questioning both the methods and overarching determination by lead prosecutor Letizia Ruggeri to find the killer.

Initially Neri seems intent on persuading us of Bossetti’s guilt – he surprisingly gives him up early in the first episode – but in the final chapter he emphasises inconsistencies in testimonies and evidence, especially the crucial DNA proof and a series of surveillance tapes of his van seemingly stalking Yara’s gym, creating doubt as to the suspect’s culpability.

As the series uncovers, there are enough problems with Ruggeri’s investigation that it is possible the collected evidence is certainly suspect, and that reasonable doubt exists.

It’s another intense narrative that centres on the messiness of police investigations and the possibility of the innocence of a convicted man. The many questions raised in the series – what mistakes, accidental or deliberate, did the prosecutor, detectives or lab technicians make? – might just lead to his possible exoneration, though that still seems unlikely after several trials and much of the evidence disappearing.

And, while Neri concentrates on the trope of the lovely dead white girl, so common in this new moment for true crime, he widens the scope of his story. He highlights the continuing allegations of misdirection, suspicions about the investigative methods used, and the possible failure of the Italian judicial system under enormous pressure from the voracious media.

Neri uses every storytelling trick in the true crime documentary manual to involve and eventually implicate us – juxtaposing archival footage, interviews with participants, including Bossetti and his wife and Yara’s parents, TV and radio grabs, phone intercepts, police investigation files and private prison recordings.

“If you start out with a presumption of guilt, you read the documents one way, and another way if you presume his innocence,” Janet Malcolm wrote in The Journalist and the Murderer, exploring the complex and often contentious relationship between journalists and their subjects

And these days you always wonder how the creators of these new-style true crime shows are shaping the material to prove their preconceived notions of guilt or innocence factually and emotionally correct. As Kathryn Shultz suggested, writing of the controversies surrounding Making a Murderer in the New Yorker, sometimes these investigations seem, “less like investigative journalism than like highbrow vigilante justice”.

You also wonder, watching this rushing kaleidoscopic range of interview material – four editors are credited – just how Neri was granted such privileged access. And on what condition so many participants agreed to go on the record, what promises were made, and whether they had any influence over the way they were edited in the final cut.

There is an enormous amount of material – the investigation went on for years – and you always consider just who profits from tragedies such as this. And just what are the ethics involved, whose permission was sought and just what was the effect on the multiple families involved.

There is almost something indecent about the pace of this series, the way Neri seems desperate to cram so much material into an already complex investigation. It’s as if he’s attempting in narrative terms to mirror the haste of the police case, the sense of desperation that hovered over the small town of Brembate di Sopra.

At times it’s sketchy and frantic as he analyses the clues and details, and establishes his own timelines, often going back over the material several times, from different perspectives, examining different possible contexts.

The many time jumps back and forth are a little bewildering, even though he provides a graphic digital ticking clock detailing time passing, taking us back and forward to different points in the story as the idea of Bossetti’s guilt or innocence shifts and slides. At times it’s as if his whole world is crumbling around him, as in Neri’s prison interviews with him he seems irrevocably lost in a system he doesn’t understand, conscious only that somehow, he had played life wrong. There is about him at the end a resigned, if bitter, concession to fatality.

The Yara Gambirasio Case: Beyond Reasonable Doubt streaming on Netflix.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout