Power to the press

PRINTS are still not well understood as an art form.

PRINTS are still not well understood as an art form.

While I was at the Art Gallery of South Australia's impressive survey of its Italian print holdings, A Beautiful Line, I heard a young woman exclaim in disappointment as her boyfriend showed her the Piranesi Carceri, "Oh, are they only prints?"

Even in the world of disembodied digital images, she remained attached to the mystique of the original, perhaps because art is still dimly perceived as a domain where things are not entirely disembodied, interchangeable and meaningless; a domain where things are still handmade and real.

Of course, she was confusing prints with reproductions made by mechanical means. Real prints are made by hand, one at a time, and there are potentially significant differences in each proof; even when a master printer editions the plate -- producing an agreed and limited number of impressions, and making them as consistent as possible -- no two are exactly the same.

I had just been reminded of this while taking part in a masterclass with Marco Luccio, who works in drypoint and who recently had an impressive show of work from his stay in New York at Australian Galleries in Sydney. Not only the etching of the plate but even its inking, or the wiping of the surplus ink, is part of the art, a deeply intuitive process that cannot be carried out thoughtlessly or mechanically.

The plate is wiped decisively yet delicately, more in some places than others, and always with a view to bringing out the character of the image. And the same plate in the hands of a different artist or with a different expressive end in view can produce a remarkably different result.

The South Australian exhibition deals with Italian printmaking from its beginning in the 15th century up to the 18th, where it concludes with fine works by Tiepolo and Canaletto, and above all with the dramatic suite of Piranesi's Carceri d'invenzione, one of the great works of 18th-century art.

The collection owes its origins to the generous bequest of a private benefactor, David Murray, who bequeathed 3000 old master prints to the gallery just more than a century ago. The AGSA subsequently purchased another 1600 prints from his estate and since then further bequests and acquisitions have allowed the accumulation of an impressive collection in a field in which it is still possible to buy masterpieces for a reasonable price. Like printing, printmaking began in the 15th century when the manufacture of paper in Europe reached a volume sufficient to support such applications. The earliest prints were woodblocks, called relief prints because it is the part of the block that is not cut away that prints as black; this is the same principle as the Japanese woodblock and allows the artist, in effect, to draw the design on the block, then cut away everything that is around it.

But there is nothing simple about this process, which could not be more different from the passive amorphousness of digital photography, with its boundless chromatic continuum and deceptive effect of naturalism. In a print, everything has to be converted into the abstract order of lines. Decisions have to be made, equivalents consciously sought out.

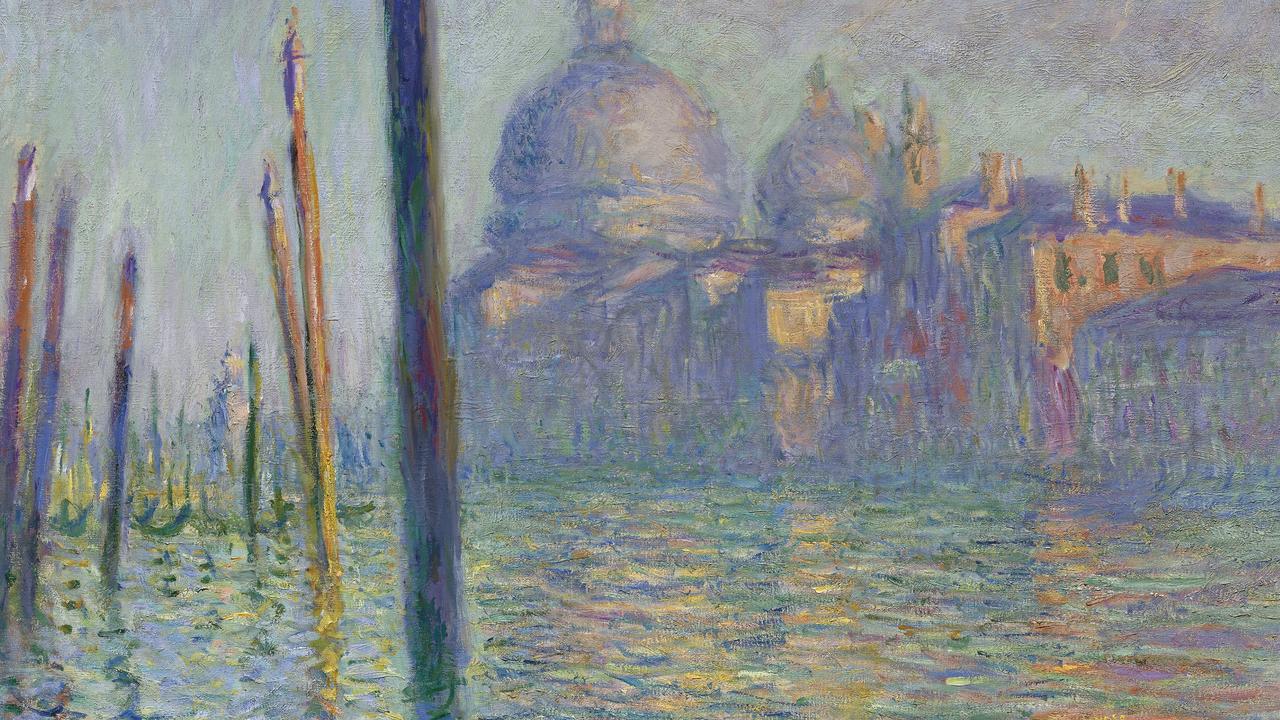

This is an essential part of the aesthetic appeal of prints. One is always aware of the artifice by which the image is produced, combining conscious choices with the intuitive action of the artist's hand. To be able to read and understand such images in this way is the basis of true visual literacy, as is the understanding of light and tone in Stieglitz's photographs or colour in Monet or Vuillard's paintings.

The transformation of appearance into graphic equivalents is also the basis of drawing, but there is an important difference: in a drawing, we can often follow the sequence of lines, washes and other elements from which the image is constituted. In a print, although the process of cutting the lines into a hard material is much more time-consuming, in the end everything comes together in the simultaneity of the impression. This arresting of time into an instant is the most mysterious attraction of printmaking.

If woodblock is a relief technique, impressions on metal plates (usually copper) are intaglio. In this method, lines are cut into the plate, which is inked and wiped; the plate is put through a press with a sheet of damp paper, and the ink is forced out of the grooves, transferring an image on to the paper.

The first method of intaglio printmaking was engraving, where the lines are cut out of the metal with a burin; in etching, the plate is covered in an acid-resistant ground, the design scratched in the ground, then acid used to etch the lines wherever the ground has been removed. In drypoint, a hard needle is used to scratch directly into the plate, while further refinements such as mezzotint and aquatint may be used to create areas of tone.

But tone exists also in engravings and etchings simply through the minute amount of ink that remains when the metal has not been over-wiped. This is called plate tone and helps to give unity to the composition; woodblock does not have plate tone since the surface of the block has been cut away, and that is why it cannot tolerate large, bare areas, which read simply as blanks, and tend to be filled with decorative linework.

An attempt to deal with this shortcoming was the chiaroscuro woodblock, in which separate blocks were used to add areas of tone to the linear design, as we can see in Ugo da Carpi's Hercules Driving Avarice from the Temple of the Muses (c.1516-17) or the same artist's Venus with Amorini Chasing a Hare (1510-30), a subject inspired by antique author Philostratus.

From a very early date engraving was adopted by important artists as a means of publishing works they had executed in painting and as a vehicle for designs made expressly for the medium. Raphael was a pioneer, producing, through his engraver Marcantonio Raimondi, exceptionally famous prints such as The Judgment of Paris and The Massacre of the Innocents, neither of which, unfortunately, is in the exhibition, though there is the less well-known Martyrdom of St Cecilia (1520-25).

The dissemination of original designs and of reproductions of important painted works revolutionised the transmission of style and artistic influence because henceforth artists could become acquainted with the style of Raphael, for example, as far away from the centre of modern culture as Paris then was. This was the case with the young Poussin.

The most important reproductive engraving in the collection is Giulio Bonasone's 1546 version of Michelangelo's Last Judgment, done only five years or so after the completion of the huge fresco. The engraving reproduces the original appearance of Michelangelo's work before Daniele da Volterra was commissioned, 20 years later and after the master's death, to cover the naked bodies with wisps of fabric.

Prints occupy a complex position within the market and the corpus of an artist's work, especially in the hands of painters, for whom they can represent a kind of supplement to their main activity. Claude Lorrain, for example, was an enormously successful artist who did not need to resort to printmaking to make money but who evidently enjoyed etching as a way of thinking about compositions in a different medium; there are two fine examples in the exhibition.

For others, such as Salvator Rosa, Pietro Testa and Benedetto Castiglione, printmaking offered an opportunity to deal with themes that were more personal or recondite and therefore less suitable for paintings, especially for public commissions. Thus the unfortunate Testa -- a sometime pupil of Pietro da Cortona who had a spectacular falling out with his master, never really achieved success as a painter and later committed suicide -- found in etching a perfect outlet for literary, philosophical and theoretical subjects.

One of his prints tells the story of Thetis dipping the infant Achilles in the waters of the Styx to make him immortal -- a tradition much later than Homer -- and another shows the gruesome suicide of Cato after the victory of Caesar: the wound he had made in trying to stab himself not being deep enough, he pulled out his own intestines and died. Finally, there is also an Allegory of Painting, one of several works in which Testa attempted to outline his anti-baroque theory of painting.

Cato was a hero of modern neo-stoicism, a philosophy that appealed to Rubens and Poussin. Rosa, best known as a precursor of the sublime landscape, also used printmaking to express his stoic beliefs, here in the famous story of Alexander visiting Cynic philosopher Diogenes, who had sought to give up all superfluous material possessions and lived in a barrel. When the conqueror of the world asked Diogenes if there was anything he could do for him, the philosopher said he could get out of his sunlight.

What is today the best known story about Diogenes appears in an etching by Castiglione: walking around in broad daylight holding a lantern, he explains that he is looking for an honest man. In Castiglione's print, however, there are no other men, only a collection of grotesque objects and animals that seem to allude to mortality, vice and superstition at the same time. Interestingly, in an artist who shows the influence of Rembrandt's etchings, we can sense an anticipation of Goya's later images of the irrational.

With the growth of the Grand Tour in the 18th century was a corresponding increase in the demand for souvenirs of these travels, which could range from extremely valuable antiquities or paintings by recognised masters such as Canaletto to more modest paintings and fine prints for a more affordable price. The exhibition includes beautiful subject etchings by Tiepolo and vedute of Venice and the lagoon by Canaletto, animated by brilliantly casual and momentary effects of light.

The exhibition ends on a grand operatic note with a wall devoted to Giovanni Battista Piranesi, who made his name with impressive and dramatic vedute of Rome and other classical sites such as Paestum, and who worked concurrently on a series of imaginary prison-houses, the Carceri d'invenzione (1745-61).

These are improvisations on the theme of claustrophobia and a confinement that paradoxically goes on and on, up staircases, through arches, into labyrinthine spaces beyond.

In the middle of the Enlightenment, these proto-romantic works are like intimations of irrational terror, of Goya's sleep of reason. Their power resides partly in the rational infrastructure of the unintelligible world evoked, partly in the surprisingly improvised linework that conjures figures out of scribbled lines, like dreams.

And instead of gazing into the depths of gloomy interiors, as we may expect, we look through shadows to a light that always remains inaccessible and pushes us deeper into our own darkness.