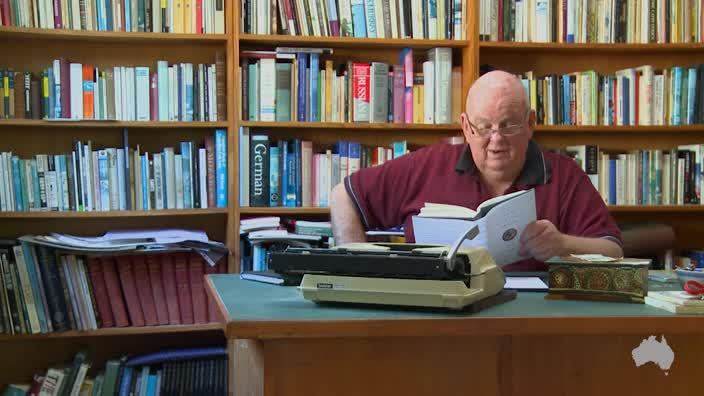

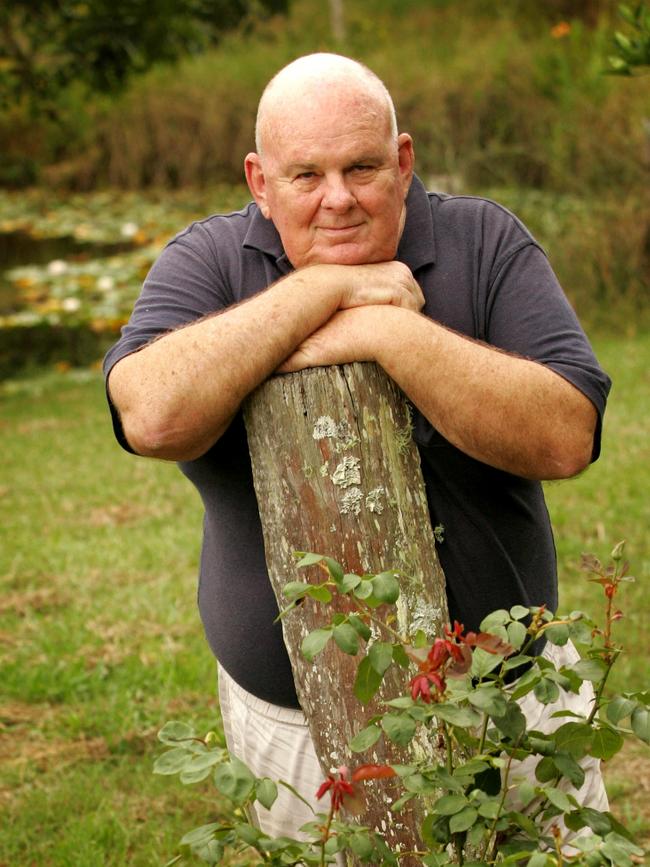

‘Bard of Bunyah’ Les Murray dies

Les Murray was a genius with words, the fodder of his lifetime.

Les Murray,

Poet. Born Nabiac, NSW, October 17, 1938. Died Taree, April 29 2019, aged 80.

He was the bush laureate, Australia’s greatest poet. He was large, shambling, brilliant and endearing. Les Murray was a genius with words, the fodder of his lifetime.

He was shy, a legacy of childhood solitude, poverty and privation. Some of that shone in his poems. His native tongue could be heard in verse that was direct and stripped of pretension.

He grew to accept respect from the powerful but never lost the connection with his origins, being a man who was down-to-earth all his life.

Murray was one of about 2000 descendants of a Scottish immigrant couple who arrived in 1848. The couple prospered in rural NSW but by the time Les was born 90 years later, his parents Cecil and Miriam were excluded from the monied side of the extended family and the boy grew up in a two-room shack at Bunyah near Coolongolook.

Read more: Trent Dalton’s feature on Les Murray in 2014

His companions were farm animals and a dog, Bluey. He taught himself to read by the time he was four. At nine, he had read his mother’s eight-volume encyclopaedia several times.

At the one-teacher Bulby Brush public school, he was more or less left to teach himself. At 12, big and very strong, he tried high school at Wyong and then Taree where he boarded briefly.

In 1951, his mother Miriam died aged 35, Cecil having delayed getting help after she haemorrhaged with an ectopic pregnancy. Her husband was paralysed with grief and guilt and Les found himself caring for his father. His childhood innocence ended in the squalor of their bush dwelling.

At high school in Nabiac, the teachers soon realised they had an exceptionally talented boy on their hands. But he hadn’t learned to socialise, so he stayed aloof from the other pupils except for a brief attachment to a girl.

His father persuaded him return to school at Taree were he arrived aged 16, a big, poor, awkward lad from the bush with a vast vocabulary among a bunch of boys and girls looking for a target on which to vent their cruelty. It was hell, he recalled.

He read constantly and excelled at English and history. He was introduced to poetry and consumed all of Milton’s work in one weekend. He discovered German and, with it, an aptitude for languages. Murray eventually became proficient, if not fluent, in 20 languages.

Sydney University offered a sanctuary from the incessant cruelties of school and the grind of farm life. Suddenly, Murray found himself in a mockery-free zone and surrounded by people who respected his intellect.

He made close friendships and wholeheartedly entered the social life of the campus. He read everything in sight but didn’t bother attending lectures, so he failed his exams and lost his scholarship.

The next year, 1958, meant relying on friends for food. They didn’t mind — Murray was good company, though scruffy and unwashed. Among his friends from that era were Geoffrey Lehmann and Bob Ellis. Germaine Greer and Robert Hughes were contemporaries — as was Clive James who was Murray’s first publisher in the student weekly Honi Soit.

To his father’s financial relief, Murray passed his exams in 1959 and won back the scholarship. He and Ellis moved into a Bondi room and set about adding layers of filth to the floor of their lodgings.

By 1961, Murray needed one more unit to complete his degree but lacked the resolve to do anything other than sleep rough, drink and hang around the Honi Soit office. He was becoming a victim of depression.

That year, people outside his university circle began taking notice of his poetry. He went to Melbourne and had poems published in The Bulletin, astounding readers and critics with his imagery and maturity. He travelled to the Top End and Queensland, taking odd jobs and risks. Back in Sydney he dossed with friends, fell deeper into depression and struggled for motivation.

In 1962, Murray’s depression lifted when he met Valerie Morelli. They married that year. Murray got a job at the Australian National University as a translator and the couple moved to Canberra where Christina Miriam and Daniel Allan were born.

Canberra did not suit Murray. He wrote that the place “would, without the least fragment of a doubt, be the deadliest, dullest, most worthless, ephemeral, baseless, pretentious, pathetic, artificial, over-planned, shithouse of a town I’ve ever laid eyes on”.

But translating was a living and Murray began writing again. He was published in the new national newspaper The Australian and, on the recommendation of A.D. Hope, the ANU Press published a book of his and Lehmann’s work, The Ilex Tree. It won the Grace Leven Prize and was favourably reviewed in Australia and Britain.

A trip to Britain in 1965 helped stiffen his resolve to get out of Canberra, which he did two years later with the family setting up home in Wales. They lived in poverty until Murray went to London where he learned that he had been awarded a $3000 fellowship — equivalent of a year’s income.

They promptly moved to Scotland, taking a 17th-century cottage near Inverness where he polished his Gaelic. It proved to be a productive period, Murray writing as much about Australia as he did of his surroundings.

They travelled through The Netherlands, Belgium, France, Spain, Switzerland and Italy, had a minor road accident and, exhausted by the breadth of European culture, headed home to Sydney.

Murray completed his degree, just, but struggled to find a job at a time when Australia was going through a period of full employment.

An old university friend, Dick Hall, was working for the Labor opposition leader Gough Whitlam. Encouraged by Hall, Murray wrote a policy paper arguing for artists to be paid from the public purse. The Australia Council emerged from the Whitlam government’s brief term in office, and Murray was one of those who helped with its birth.

In 1969, he published his first solo book The Weatherboard Cathedral which Kenneth Slessor, then Australia’s most popular living poet, described as “a new and vital impulse” and “full of magnificent poetry”.

A meeting with ANU chancellor and head of the Aboriginal studies institute, H.C. Coombs, led to a job offer in Canberra, editing an anthology of Aboriginal poetry. The family decamped to the national capital but the job fell through. They were in financial difficulties but survived thanks, once again, to Valerie’s teaching experience.

Murray landed a job in prime minister John Gorton’s office answering the PM’s mail. It was a living, he reasoned. In 1972, he won $2500 (when the average annual wage was about $3800) in a competition marking the bicentenary of Captain Cook’s arrival at Botany Bay.

The constant moving, Murray’s bouts of depression and financial insecurity briefly threatened his marriage. Murray went walkabout and Valerie took the children to Sydney, got a teaching job and bought a house. Stability at last. Murray joined them and began working harder then ever. He had a mortgage now.

In 1971, after quitting yet another dead-end desk job, he decided to become a full-time freelance poet. He gave readings, lectured and wrote. Poems Against Economics was published, confounding critics who failed to appreciate its experiment with a long, meditative form.

He became acting editor of Poetry Australia and stayed for seven years (unpaid). He proved to be a natural editor, always prepared to help with honest, sharp, often blunt advice — usually accepted by his contributors who knew he was right.

His next volume Lunch & Counter Lunch attracted some envious critical sniping but David Malouf said it had “astonishing dexterity”, while Kevin Hart wrote about Murray’s “purification of the Australian vernacular into poetic language”.

Murray had already begun reviewing for newspapers and in the mid-70s this form of writing evolved into essays, many of which were published in anthologies. His subjects varied from the republic (he was a firm republican) to arts funding.

His bank balance now in the black, Murray was able to buy back a piece of Bunyah and build a timber house for his father. He was also planning to eventually move back to the bush-place of his birth — which they did in 1985.

Meanwhile, Clare Louise was born in 1974, Alexander Joseph Cecil in 1978 and Peter Benedict in 1983. He was strict with Daniel and Christina, frequently slapping them for minor offences, or none at all. But the new arrivals saw an end to Murray’s unpredictable behaviour with his children.

By 1980, Murray had been eased out, against his will, of the editorship of Poetry Australia but he was able to fall back on reading for Angus and Robertson where he was paid a derisory $1000 a year, surely one of the meanest sums ever paid by a publisher.

The job gave him influence over the nation’s leading poetry list, a position that attracted plenty of envy, politics and back-stabbing. It wore Murray down until he resigned in 1991, citing a leftist ideology promoted by his enemies at the expense of literary merit.

Amid his struggles with publishers and critics, his output continued: Ethnic Radio, The People’s Otherworld, The Vernacular Republic and The Boys Who Stole The Funeral.

The latter was a verse-novel that upset feminists, the white Aboriginal lobby and some old friendships. Murray’s basic non-conformism might partly explain his difficulties with leftist-liberals, a grouping he came to see as restrictive of free expression. The controversy, especially the involvement of poet Judith Wright, was an early skirmish in the so-called culture wars. Murray’s arguments proved to be superior and his opponents quit the battle muttering behind their hands.

He infuriated the Left further in 1996 when he revealed he had seen historian Manning Clark wearing the Order of Lenin, prompting Brisbane’s Courier-Mail to accuse Clark of being a Soviet agent of influence. Given Murray’s prodigious memory and interest in military decorations, it is possible that his sighting of the medal was accurate although the Australian Press Council later upheld a complaint against the press reports.

He annoyed republicans in 1999 by helping John Howard write a constitutional preamble, triggering attacks by those he described as the elites.

He was literary editor of Quadrant and survived an attempt to dump him over his nonconformist ways. He was awarded the Queen’s medal for poetry and, with Subhuman Redneck Poems, he won the T.S. Eliot prize, quietening his chattering band of Australian critics.

He had more than 30 books published, was awarded numerous other prizes and honorary doctorates and travelled the world as a visiting fellow and writer in residence.

In June 2007, Dan Chiasson in The New Yorker described Murray as among “three or four leading English-language poets”. He was mentioned as a possible Nobel prize winner in 2010 but said he didn’t want one.

He published seven volumes since 2010, the last being a collection last year.

Murray retired as literary editor of Quadrant in late 2018 for health reasons.