Nothing amiss with Larkin's enduring love

IF one talent remains to the once mighty English novelist Martin Amis, it is the ability to disguise mean-spiritedness with the vivid colours of his prose.

IF one talent remains to the once mighty English novelist Martin Amis, it is the ability to disguise mean-spiritedness with the vivid colours of his prose.

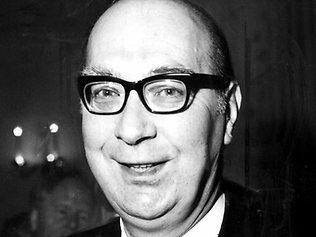

Amis's essay on "Philip Larkin's women", published in these pages last week, is a typically brilliant and misanthropic examination of the poet's personal failings based on newly published letters between him and his lover, muse and late-life companion, Monica Jones.

Having read 450 pages of Letters to Monica, a selection of Larkin's side of the correspondence between 1945 and 1970 chosen by the poet's friend and literary executor Anthony Thwaite, Amis ponders "the abysmal mystery of Larkin's life, with its singularly crippled eros" and finds in Jones the exemplary instance of his troubles with women.

The worldly and attractive blonde who lectured in English literature at the University of Leicester is, for Amis, "a small-community 'character' " and a "congenital . . . windbag" with "a restless self-importance unaccompanied by the slightest distinction", whom Larkin was simply too cowardly and passive to abandon.

Aside from reiterating the animus maintained towards her by his father, Kingsley -- whose cruelly funny portrait of Jones is contained in his first novel, Lucky Jim -- Amis's "inside information" consists of a single evening spent with Larkin and his partner in 1984; the remainder comes from the Letters, a reading so lit up by inherited rancour that half the story ends up thrown into shadow.

First and foremost, Letters to Monica is the record of a meeting between kindred spirits. "I have always felt quite out of touch with the norm and the status quo," Larkin writes in an early letter. "The idea of entering into it and being successful in it & caring about it. . . . As you say, c'est pour les autres." And this sense, that life is somehow for others, elsewhere, is one the correspondents shared. Both were clever offspring of the rising British middle class. Yet both attended Oxford when older social structures had not yet expanded to admit them comfortably. University widened their horizons, at the cost of a certain alienation from family and roots. Although they didn't meet until afterwards, those "three underbred years" (in Larkin's words) made them a party of two: clever yet diffident; ambitious but timid. Each cleaved to their jobs (Larkin was chief librarian of Hull University's Brynmor Jones Library for most of his adult life), their patch (shared holidays within the British Isles) and their (overlapping yet distinct) literary tastes.

Of course, the signal difference between them was Larkin's poetic gift, and his growing public stature is the one evolving feature of their static lives. But where Amis regards this disparity in talent as disqualifying a true relationship of equals, the letters reveal more complex affiliation. As a woman, Jones did not challenge or compete with Larkin the way Kingsley Amis and others of his generation tended to. But as a scholar of English literature she was more than equal to the task of responding judiciously to his poems. And, as his lover from about 1950 onwards, she could speak with a directness and intimacy that no colleague could: "Oh, I am sure that you are the one of this generation!" she wrote in 1955. "You will believe me because you know it doesn't make any difference to me whether you are or not."

When Larkin was well, the exuberant affection contained in Jones's letters was a passion to be managed; however, when he was out of sorts or (as, on the evidence of these letters, he often was) plagued by anxiety, self-loathing and fear, it was Jones's words to which he clung.

The fact of these letters, for the most part plentiful and regular as clockwork, is evidence that Larkin could explore desolation, loneliness and terror at the idea of death in his poems because his daily existence was underwritten by mundane, untiring, quasi-marital love. Having read a V. S. Pritchett essay on the letters of Thomas and Jane Carlyle, Larkin quotes a passage from it in a letter to Jones that eerily reflects their own situation.

Their worst agonies seem not to have come from their common hypochondria, her jealousy or his monstrous selfishness, but from not getting letters from each other on the day they expected when they were separated. Do you think people will write like that about that us when we are dust? My dear Rabbit!

Amis does not write like that about them. He reads Letters to Monica against the grain of this need and so misses much that is worthwhile. He is particularly scathing about the slack quality of Larkin's prose when compared with letters sent to male friends and other writers, concluding that Larkin's heart wasn't really in it. Well, perhaps. But are the letters and emails we send to those closest to us not also the most relaxed? It is interesting to note that Larkin's letters most often show compositional strain when he is attempting to distance himself from Monica, particularly during his several other love affairs.

No. What makes these letters unique -- and uniquely precious -- is their plainness, a simplicity of expression and thought that mirrors Larkin's poetic method. More extraordinary than any bardic posturing is the demure insertion of highly significant items into the letters; as on Valentine's Day in 1956, when Larkin sends Monica a "token" he has been working on called An Arundel Tomb, a poem whose final lines will eventually read:

Time has transfigured them into

Untruth. The stone fidelity

They hardly meant has come to be

Their final blazon, and to prove

Our almost-instinct almost true:

What will survive of us is love.

Geordie Williamson is The Australian's chief literary critic. He helped catalogue letters from Monica Jones's estate for London bookseller Bernard Quaritch before their sale to Oxford's Bodleian Library in 2004.