Tognetti’s ACO tackles Bach’s Goldberg Variations with strings

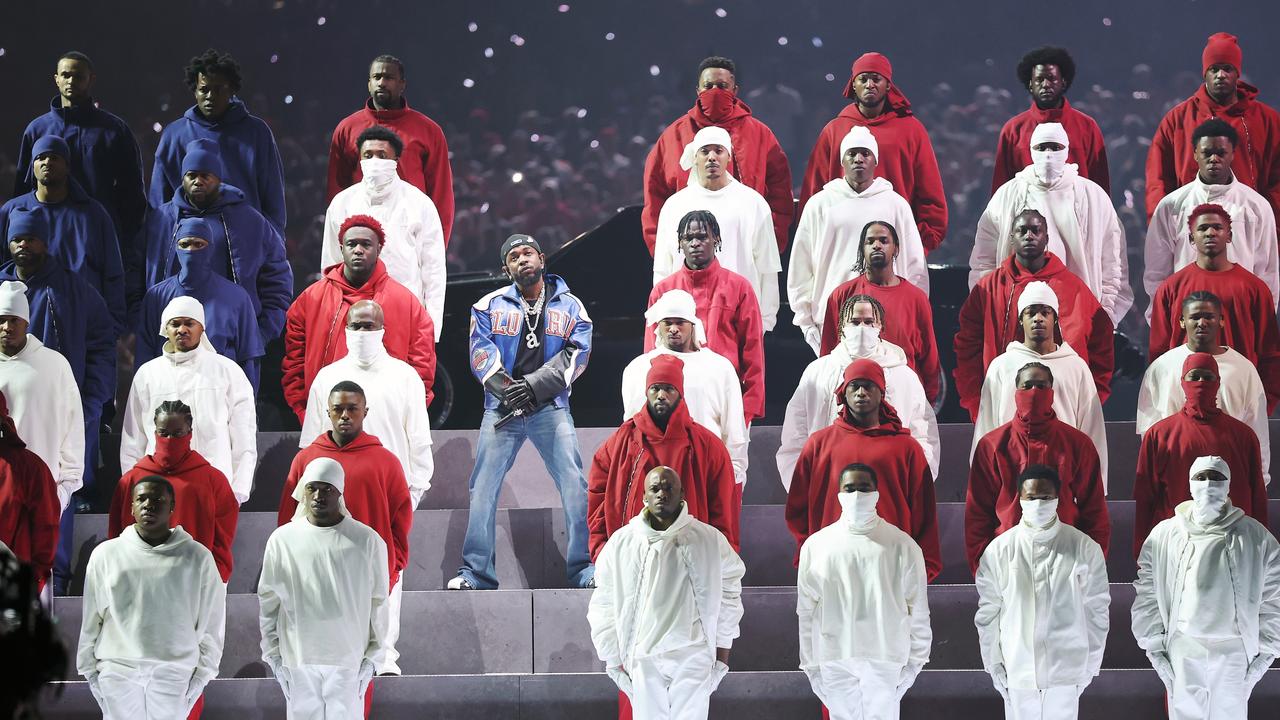

Bernard Labadie’s version of the Goldberg Variations exchanges the keyboard for a string ensemble with continuo.

Sometime before 1741, the story goes, Count Hermann Karl von Keyserling commissioned from Johann Sebastian Bach a set of musical compositions of “a smooth and somewhat lively character” that would help relieve him of insomnia. The count’s household included a gifted young musician, Johann Gottlieb Goldberg, who was kept on call throughout the night in the event the count had trouble nodding off. He was the first to perform Bach’s ingenious album of harpsichord music that now bears his name.

Today we know the Goldberg Variations as one of the summits of the keyboard literature: a simple “aria” of serene, almost melancholy beauty and 30 variations on it that exercise all of the performer’s technical and artistic capabilities. At the end the aria is repeated, returning performer and listener to a state of repose.

There is no evidence that the origin story of the Goldberg Variations has any basis in fact, although the Australian Chamber Orchestra’s Richard Tognetti finds the legend appealing and even useful. Its truthiness aids another kind of understanding — about the conditions of music-making in the early 18th century, for example. And if we’re prepared to entertain the fake news of an insomniac count, let’s not be too strict with Bach’s keyboard music either. Here we enter the realm of interpretation and adaptation: the Goldberg Variations variations.

Tognetti’s next concert tour with the ACO has been programmed around the Goldberg Variations not as usually performed on keyboard, but arranged for string orchestra. “As soon as you play it on any instrument but a harpsichord, you could argue that it’s an arrangement,” Tognetti says. “Let’s not get into the notion that you should only play what you imagine the composer intended.”

Indeed, several arrangers and groups over the years have made the Goldberg Variations their own, from vocal outfit the Swingle Singers to Jacques Loussier’s jazz trio and a recent version by the Italian baroque specialist Rinaldo Alessandrini — such is the allure of this music across the sprectum of interpreters. Tognetti has chosen for the ACO a version he admires by the Canadian conductor Bernard Labadie, exchanging the keyboard for a string ensemble with continuo.

Speaking from his home in Quebec City, Labadie says he was looking for an arrangement to perform with his early-music group Les Violons du Roy in the mid-1990s. He considered a string arrangement by Dmitry Sitkovetsky, but found it trying too hard to match the keyboard original note for note, and paradoxically not sounding like baroque music.

The variations are not based on the aria’s melody but on the step-like bass notes that supply the harmony. In the liner notes for his landmark 1955 recording on piano, Glenn Gould writes that this “noble bass binds each variation with the inexorable assurance of its own inevitability”. Labadie, like Gould, is a Canadian but is no fan of the idiosyncratic pianist who half-sang and mumbled through his recordings.

In his version of the Goldberg Variations Labadie attempted something other than a direct keys-to-strings transcription: he wanted to write a piece that would be idiomatic for baroque ensemble or “like a concerto grosso on acid”, referring to a common instrumental form of the period.

“The idea is not to reproduce the sound of the harpsichord: the idea is to use a string ensemble in the way a baroque composer would have done it,” he says. “I wanted to have an approach which was coherent with the way a musician in the 18th century viewed music — as material which could be transformed and moulded according to his own desire.”

Sitkovetsky’s method, Labadie says, was to use string instruments that would cover the range of harpsichord notes, from bass to treble, in any one variation. Labadie’s approach was to consider how many individual “voices” Bach wrote into a particular variation, and to deploy the instruments accordingly, whether it be a duet for violin and cello or a trio-sonata for two violins and continuo.

Listening to Labadie’s Goldberg Variations with Les Violons du Roy, one is reminded at times of the Holberg Suite, Grieg’s 1884 work for strings written in baroque style. An obvious difference is the absence of a keyboard’s crisp articulation and the sense of spontaneity that is possible in a solo performance. The harpsichord is here relegated to the continuo section, the harmonic backfill that is a characteristic of baroque ensembles. Labadie has retained some ornamentation but many of the decorations that are appropriate in keyboard music have been let go.

“It remains ferociously difficult technically,” Labadie says of his string adaptation. “Some of the solo stuff is very demanding and highly virtuosic — but so are Bach’s sonatas and partitas for solo violin, or the cello suites. So the extreme technical difficulty of some of the variations is consistent with the extreme difficulty we have with some of his solo writing for strings.”

Tognetti considers another aspect of adaptation. Music written for a solo instrument — such as a harpsichord, piano or violin — will produce only a single source of sound, although a skilful musician can create the illusion of that sound having various dimensions. With music written or arranged for orchestra, Tognetti has multiple instruments at his disposal and a greater opportunity to shape the “depth of field” of the ensemble sound.

The concert program includes Tognetti’s 2012 string arrangement of the Canons on the Goldberg Ground. In 1974, researchers discovered Bach’s own printed copy of the Goldberg Variations, on the back page of which he had handwritten 14 short canons derived from the Goldberg bass notes.

“All you need to bring Bach alive is clarity, a strong sense of structure and harmony,” Tognetti says of arranging Bach for string orchestra. “Otherwise it doesn’t matter if you are singing, or playing on tuned glasses.”

Tognetti says he is considering whether to ask the evening’s harpsichord player, Erin Helyard, to perform the Goldberg Variations aria as a solo during the concert. One could say that, given the keyboard origins of Bach’s extraordinary music, it would be impolite not to ask.

The Australian Chamber Orchestra presents the Goldberg Variations on tour, August 2-16.