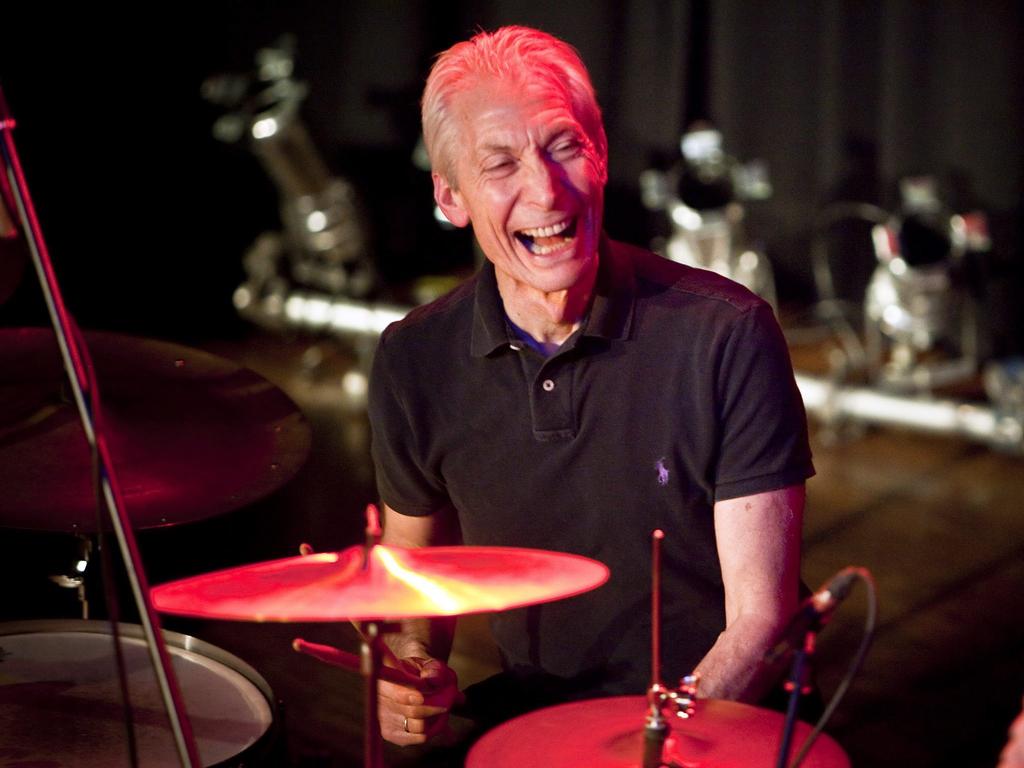

Stones drummer Charlie Watts: Always late, but never behind

Charlie Watts’ signature style was hardly textbook, but it won him many admirers among fellow drummers.

Charlie Watts was late.

A jazz drummer, he was late getting into rock ’n’ roll. Elvis meant nothing to him until he met Keith Richards. Watts preferred boogie woogie piano stylist Fats Domino.

He was late getting into drugs. When bandmates Richards and Mick Jagger were busted for drugs at Richards’ mansion in Sussex in 1967, Watts was 75km away in Lewes, at home with wife Shirley planning a family. Daughter Seraphina was born the following year. It took until 1983 for him to get in trouble with alcohol and heroin.

And he was late shifting from his hi-hat to the snare drum, an unintended quirk that saw him just behind Keith Richards’ chugging riffs and defying their gravitational pull. Few drummers could do that, but it was the most rock ’n’ roll thing he ever did. Perhaps the only rock ’n’ roll thing he did. He didn’t even know he was doing it until session superstar Jim Keltner pointed it out in 1969.

By then a few drummers had copied that style, or always played like that anyway, notably the Band’s Levon Helm. Keltner admits he stopped being as busy around the kit after seeing Watts and, he says, so did Steve Jordan from The David Letterman Show band. Watts had already chosen Jordan to sit in for him on the Stones’ upcoming American tour. Nonetheless, it is not a technique described in any drum manual. Any teacher would quickly “correct” it.

You can hear it clearly on Tumbling Dice. You can see it on Start Me Up.

It became as much a part of the Rolling Stones brand as Richards’ irregular chords and Jagger’s depthless vocals – but they remain rock’s holy trinity of sounds. (The truth is only one great musician has passed through the band’s ranks: Mick Taylor. On record, the Stones contained their gifted young guitarist, but anyone who saw the band between 1969 and 1975, particularly the 1973 tour of Australia, can attest to his skills.)

Watts’ playing looks awkward, with his right hand ostentatiously making way for left so that he can better strike his snare, perhaps unconsciously developed so that he could be heard in clubs before the drums were regularly mic’ed up.

And while never missing a show in 58 years, Watts did “miss out” on two of the Stones better-known moments. Late in 1973, soon-to-be-a-Stone Ronnie Wood hosted a late-night session at the studio he had built in the basement of the historic London house, The Wick, on Richmond Hill (now owned by the Who’s Pete Townshend). Jagger and David Bowie were there – Richards lived out the back – as was George Harrison’s preferred bass player Willie Weeks. From a jam emerged what would become the song It’s Only Rock ’n’ Roll. Wanting to nail it, and knowing Watts was on the continent, Wood called Faces bandmate drummer Kenney Jones to join them (and he would replace Keith Moon in the Who). Much of the song was reworked, but that is the original rhythm track you hear with a disciplined Jones doing his best Watts impression.

While recording You Can’t Always Get What You Want, Watts had trouble following the groove producer Jimmy Miller (Kerri-Anne Kennerley’s first husband) had set down. Miller sat behind Watts’ always modest kit, and played the rhythm he was seeking. Watts tried it again. Miller showed him once more. Miller (who also played on Happy and Shine A Light) said later: “Charlie, who was lovely and humble, said, ‘Jim, that sounds great, you play it’.”

This was the “lovely and humble” Watts who is supposed to have punched Jagger after the singer referred to him as “only my drummer”. But only Richards, who is given to making up stories – including that he snorted his later father’s ashes – seems to remember this and the various versions of it. “Memory is fiction,” he famously wrote in his biography, Life.

On the Stones’ last tour here in 2014, their saxophonist Tim Ries was booked to play a night at Sydney’s 505 jazz club in Cleveland Street, Surry Hills. Ries has recorded two albums of jazz interpretations of the band’s songs. Watts and the Stones’ bassist Darryl Jones were there and both joined Reis for his version of the Stones’ 1981 hit Waiting On A Friend. Word had been out that a Stone or two might front. The venue must have been unaccustomed to a full house. A note was hung on its door: “Sold out. Really.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout