Michael Hutchence and INXS: searching for a new angle in Shine Like it Does

A new account of Michael Hutchence reveals a loner who hated solitude, an unfaithful romantic, and a shy boy who sang before thousands.

After all this time, what is left to say about Michael Hutchence? That was the question I wrestled with when I set out to write Shine Like It Does. The INXS singer, now 20 years gone, has remained in the public imagination. The records still sell, the band has been fictionalised, and its members have appeared on reality television and in authorised biographies.

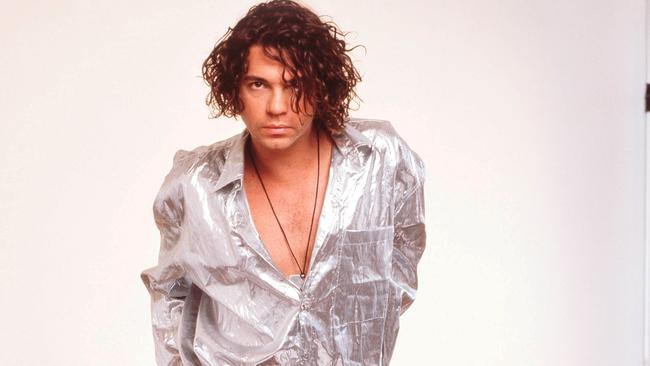

Hutchence was, without question, one of the truly great frontmen — he expressed the music in a dynamic way that few others could. His liquid stage performance made Michael Jackson look like a creaky robot. The challenge was to do him some justice and not just add to the tabloid nonsense such as played out in recent documentaries.

Hutchence was a man of contradictions. He was endlessly curious and so his head was full of ideas. As John Le Carre wrote (channelling F. Scott Fitzgerald): “An artist is a bloke who can hold two fundamentally opposing views and still function.” That was Hutchence. A loner who hated solitude; an unfaithful romantic; a shy boy who played to 25,000 people. He loved pop music as much as he loved atonal noise; he loved sublime masterpieces and things that were trashed and crazy (but not much in between); he was fiercely ambitious but also abhorred the idea of a career, hence taking film roles that could trash his reputation.

In the first place, INXS epitomised the 1980s like few other artists. The band was sexual and flashy, it put together dance and rock music. INXS, despite the hard work it put in, looked like a travelling party. The 80s was the decade of big shoulders and big beautiful hair (on women), of big sounds and broad gestures. The times suited INXS.

The 80s was also the decade of MTV. Music television caused a boom in the record industry and most of it came from the melding of sound and image. MTV also melded R&B and rock music for the first time. Jackson’s Beat It set the tone for the decade and INXS fitted right in. Its song Original Sin was a game changer in Australian music. Then the band teamed up with filmmaker Richard Lowenstein, who had a unique eye and sensibility. Those calculated risks set INXS up. Hutchence’s charisma, of course, helped.

Tim Farriss, the band’s lead guitarist, once said that so many articles and books on INXS touched on the hard work, the grind and the later tragedy, but don’t convey the fact that this was one great adventure.

For the most part, these people were having the time of their lives. It was big fun. Even when there were the inevitable feuds, the core excitement and solidarity was there. INXS and Hutchence had a background in post-punk pop and they retained that experimental edge in their work while adding a rock and soul feel and a gift for melody. That was a rare combination in the mid-80s.

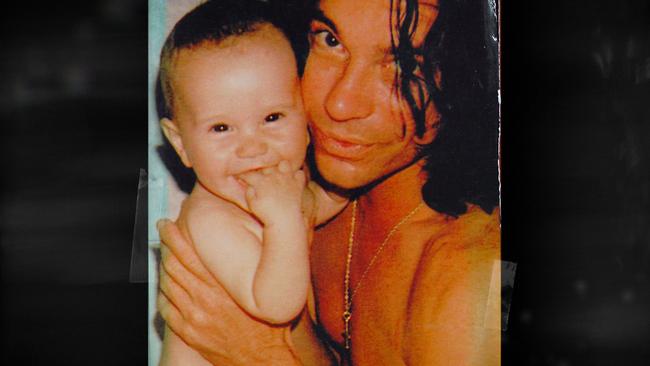

Then there was the work ethic: an ability to spend months and months crisscrossing North America and delivering unparalleled live shows. INXS was one of the great live shows of the decade and Hutchence was an extraordinary frontman. One reason the band could keep up this gruelling schedule was the internal camaraderie and commitment. That never completely fractured. While there have been headlines suggesting that Hutchence wanted to leave INXS, his close friends suggest that his commitment went much deeper than difficult periods with the band. INXS was like a family to Hutchence and, despite sometimes bitching, family was what he was searching for, right to the end. Certainly there were problems but in the long term they would have been sorted.

Looking for a different angle, I thought it might be interesting to have a look at Hutchence as an artist. Although he was a cocained sex god, he was serious about his work. He knew his limits and he pushed them hard. He sought out innovative and sometimes uncomfortable artists and really wanted to learn from them. Sometimes it worked, sometimes not. But he was not a guy who just chased la dolce vita. He was equally at home, as his friend Greg Perano said, drinking with street kids in Paris as swanning through opening nights.

Mostly I wanted to have a sense of what it means to make it: how the pub rock era worked in Australia and what success looked like afterwards. People talk about success in general terms but I wanted to explore what it’s like to have a multi-million-selling album and what that does to a person, how it changes their life.

INXS was a classic case of a group that got to the top of the mountain but the sheer strain and exhaustion of the trip changed them. And while there at the peak, everything changed around them.

Hutchence was a sweet guy, partly truth and partly fiction. His work was incredible. Go and listen to those INXS records again, especially the later ones with tracks such as Men and Women, The Gift and Searching, and dig out Max Q tracks such as Sometimes. Hutchence made the complex look simple. He climbed up on the high wire and he kissed and told all his fears.

Doing research for the book I was told about the time, in 1988, INXS played Palais Omnisport de Paris-Bercy in the City of Light. The group had been on a long and grinding quest, 10 years or more on the road, from the dusty Australian outback to the American plains. Their determination was matched by their hard partying.

It was like Satyricon and Scarface mashed with a Carry On film. Over time the road had changed them all, but especially Hutchence, from gormless suburban boys into a sophisticated unit whose creative ideas now influenced hundreds of other artists all over the world. But on the evening in question they were on the last leg of this Napoleonic campaign.

The finish line loomed, and not a moment too soon. INXS’s manager, Chris Murphy, had banned all drugs from the tour entourage and everyone was clean and cheerful.

But this was Paris. The intro music stopped and the band rushed to the stage; Tim Farriss was doing his funny walk — he jumped on his skateboard — and Jon Farriss covered the searing pain in his knee bones to hit a punctuating drum beat. It started: the tsunami roar of the crowd, the huge, wide desert sound that INXS made, and Hutchence bouncing, dancing around. He came to the side of the stage, looked at Murphy and popped two ecstasy tablets straight down the mouth, laughed and danced to the front of the stage. He spread his arms wide, his shirt now off, and arched his back. Almost on tiptoes he threw his head back and yelled “Je t’aime, Paris! I want to f..k you!” and the audience roared back the same words in French.

Then there was another Hutchence.

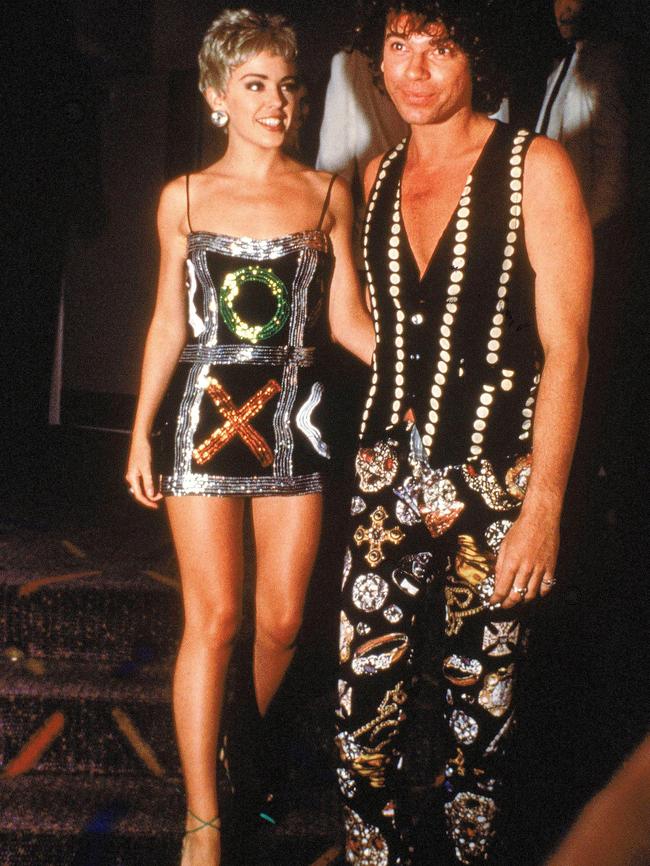

Late on Christmas morning in 1989, I walked down Oxford Street in Sydney — usually the street of bars and debauchery, but that day as quiet as a mouse. There, on the corner of Oxford and Wentworth Avenue, stood Hutchence with his arm around Kylie Minogue. He looked confused. It was Christmas but Hutchence wanted to know if there was anywhere they could get a coffee and breakfast. Of course they could have gone to any five-star hotel in town. But that would have seemed like the working life. Today they were enjoying the real world. I sent them to the Tropicana (then just a hole in a Darlinghurst wall), one of the few joints open.

I saw them later that morning. The two most famous Australians in the world, drinking cappuccinos and lost in each other’s gaze. Two kids in love.

Toby Creswell is the author of Shine Like It Does: The Life of Michael Hutchence, published next month by Echo.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout