ARIA 2022 sales data: music streaming is up, but Australian acts being left behind

The streaming boom has seen music sales hit heights not seen since 2006 — but Australia’s current top 50 features just one local artist. It’s a stat that has ARIA gravely concerned.

Recorded music sales data released by ARIA on Wednesday contained both welcome and troubling news for the sector.

According to the Australian Recording Industry Association, which represents record labels large and small, overall music sales hit a 16-year high in 2022, totalling $609.6 million.

These are heights not seen since 2006, when CD buying was still commonplace, iTunes downloads were en vogue, and streaming subscription services such as Spotify and Apple Music were not in play.

Annual wholesale figures have grown for the fourth consecutive year, up 7.4 per cent from $567.8m in 2021 – a growth figure that exceeds markets like the US, Britain and France.

Last year, subscription streaming services rose 8.9 per cent to $410.7m, comprising 67.4 per cent of the industry. Overall, digital sales account for 90.4 per cent of all music sold in Australia – more than 50 per cent higher than sales figures from a decade ago.

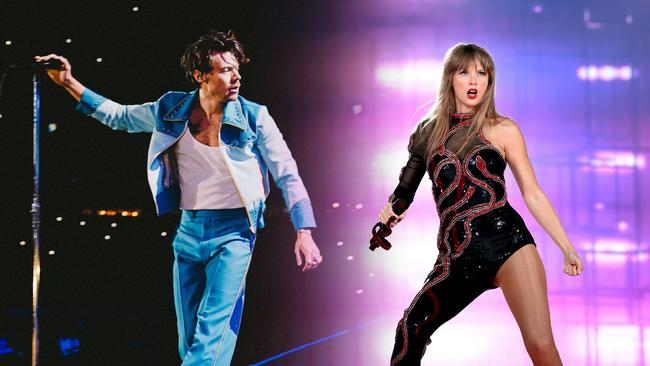

In 2022, when ARIA’s end-of-year single and album charts were topped by British singer-songwriter Harry Styles and US pop artist Taylor Swift, respectively, vinyl sales increased slightly – 1.149m, up from 1.141m – while CDs continued to decline, recording 1.97m sales last year compared to 2.385m in 2021.

That’s the good news.

Here’s the bad, as far as local artists and labels are concerned: in the current ARIA album chart, for the week of March 20, only one release in the top 50 belongs to an Australian artist.

That is Fremantle indie rock band Spacey Jane, whose second album, titled Here Comes Everybody, sits at No.41, having debuted in the top spot in July last year.

This week, Spacey Jane appeared on the list amid a sea of mostly American and British acts, with a new release by US pop singer-songwriter Miley Cyrus debuting at No.1.

With the vast majority of domestic listeners regularly choosing to listen to music made overseas, it’s a seemingly intractable issue and a tough commercial reality for artists and record industry workers alike.

For ARIA chief executive Annabelle Herd, it’s an ongoing concern, as that sole chart appearance – representing just two per cent of the top 50 – “proves the need to develop an urgent strategy with all players involved in the Australian music ecosystem to ensure that the growing number of Australian music lovers can connect with Australian artists,” said Herd.

Given that both the singles and album chart are driven by streaming numbers as a pure popularity contest, however, it is unclear how that “connection” can be regained.

The ubiquity of streaming services are clearly showing that Australian listeners are choosing to stream the likes of Styles – whose albums currently sit at No.2 and No.9 – Pink (No.3), Morgan Wallen (No.4) and Ed Sheeran (No.8 and No.10) instead of homegrown artists.

Asked to expand upon that idea of connecting music lovers and local artists, Herd told The Australian, “Part of the issue is that we don’t have a complete answer on how to solve the problem, we’re just very aware that it exists. It’s why we need the best brains in the country – from the people working in music to government – to consider a whole-of-industry plan to get Australian music listening and discovery back on track.”

“We don’t want to become a subsidised industry,” she said. “We want to be one that is commercially viable and contributing to the national GDP. It’s clear we have the audience to do that, and the talent certainly exists in Australia, but the missing link is how to effectively connect the two.”

“We certainly do need greater transparency from the streaming platforms as to how playlisting works and how discoverability is driven, as this plays a huge role in getting local music heard,” said the ARIA boss. “However, the fact that subscription streaming accounts for such a large slice of the pie isn’t so much an issue to address as it is an opportunity to work with these platforms to get more new Australian music heard. And the solution doesn’t start and finish with streaming, it’s just one piece of the puzzle.”

Charged with attempting to solve that puzzle is Music Australia, the new $69.4m body announced under the federal government’s national cultural policy in January. Its mission is to promote Australian songwriters and musicians, both locally and internationally.

“We need to double down on promoting more Australian touring so more music fans can reconnect with local artists in a live setting through initiatives like Great Southern Nights,” Herd told The Australian. “We need to examine commercial radio quotas to ensure they play their role in promoting new Aussie music in the right timeslots, which still plays a role in discovery. We need to ensure the industry has access to the right educational support and resources, similar to what Australian Film and Television have with AFTRS. These are all significant factors for Music Australia to consider as they develop their plan, but the industry also has a huge part to play.”

For years now, as streaming has dominated roughly two-thirds of the recorded music market, the best outcome that an Australian artist can hope for on the ARIA chart is a strong debut, most often due to pre-sales ahead of the first week of release.

What usually follows for even the biggest Australian albums issued each year is a decent showing of streams and sales in the first week – then a sharp drop off the ARIA chart cliff, probably forevermore. (In this sense, Spacey Jane’s second album is a true outlier: it has spent a remarkable 23 weeks in the top 50 since its release in June last year.)

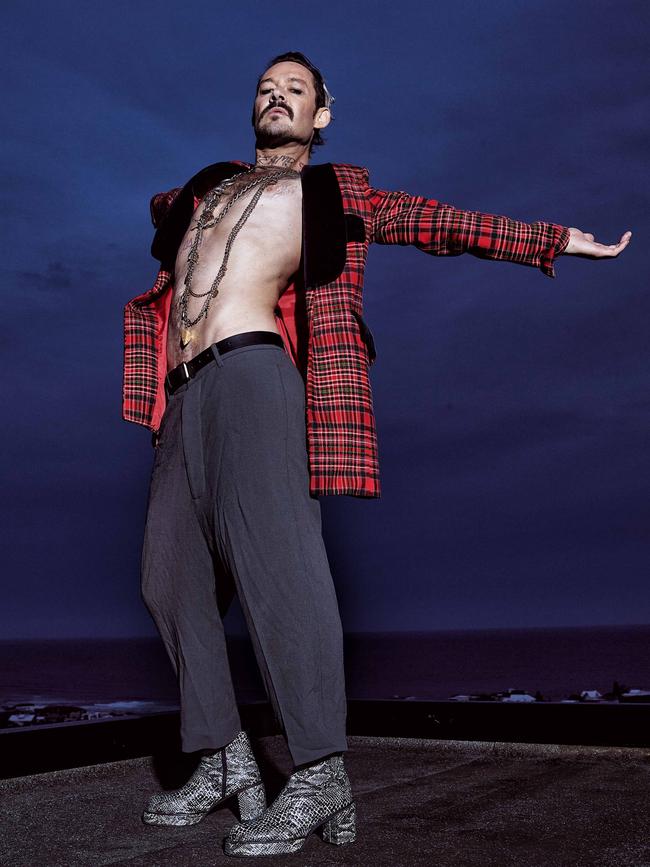

In this sales environment, it is becoming exceedingly rare for an Australian album to stick to the upper reaches of the ARIA chart beyond week one, which is part of the reason why former Silverchair frontman Daniel Johns’s FutureNever was a captivating story for local music industry watchers last year.

Released in April, Johns’s second solo album was accompanied by his record label BMG’s canny release strategy, which centred on unique and desirable merchandise offerings bundled with digital album sales.

FutureNever debuted at No.2, reached No.1, then spent six weeks inside the top 10 and 11 weeks inside the top 20. In October, Johns did the near impossible: he reclaimed the No.1 spot after 22 weeks, ahead of The Weeknd and Harry Styles, following its delayed vinyl release.

In terms of wider cultural impact, FutureNever was ultimately negligible: on Spotify, its highest-streaming song, I Feel Electric, has 1.2m plays, while its closing track has been played just 125,000 times. (For comparison, Spacey Jane’s song streams range from 22.4m to 1.2m across its album.)

In other words: barely anyone heard Johns’s album, and beyond the first week, only his hardcore fans (and perhaps chart nerds) were paying attention to its songs.

All of which puts ARIA in a tricky spot as the peak recording industry body: its press release on Wednesday led with lines such as “Australian music celebrates four years of growth” and “2022 sales data reveals highest sales since 2006”.

But with streaming driving the recorded music industry, and Australian listeners regularly choosing to listen to music made elsewhere, celebrations within the offices of record labels nationwide were likely to be minimal, if not muted.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout