Major exhibitions coming to National Portrait Gallery and National Gallery of Victoria

Can an abstract painting be a portrait? Two exhibitions coming to Canberra and Melbourne are an opportunity to assess the value we put on ‘true likeness’.

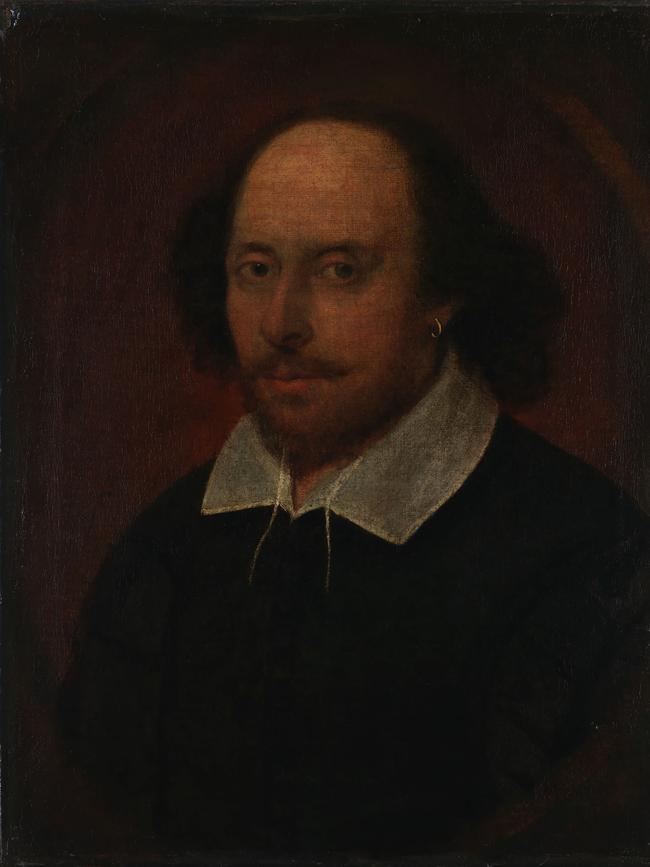

The eyes are shifty, giving a sideways glance. Dark, slightly curly hair retreats from a high forehead. Is the man smiling? He wears a white collar and black doublet, fashionable in the early 17th century. With his gold earring, he could be a middle-aged Jacobean hipster, a pirate or, indeed, a playwright.

William Shakespeare is the name, and the portrait of one of the most famous images of the author of Hamlet, Macbeth and The Tempest. It was painted by John Taylor in about 1600-1610 and, being one of the few contemporary depictions of Shakespeare, it has enormous cultural significance. It is virtually the foundation stone of Britain’s National Portrait Gallery, which on its opening in 1856 designated Shakespeare’s portrait NPG1.

Visitors to Australia’s National Portrait Gallery in Canberra will soon have the chance to inspect the Shakespeare portrait in an exhibition from the British collection called Shakespeare to Winehouse. But is it really a portrait of Shakespeare, or the portrait of another man who later generations would like to think is Shakespeare?

The claims to authenticity lie somewhere between scholarly research and wishful thinking: a kind of art-historical “to be or not to be”.

Alison Smith, chief curator at the British NPG, says the painting nevertheless speaks to the enigma that is the historical Shakespeare.

“He has a marvellous output of plays and poems, but we know very little about his life,” she says. “We don’t know much about his religion, his sexuality, did he travel overseas – all these questions about Shakespeare. So the portrait is somehow a way of locating him, or fixing him. It’s the mystery surrounding Shakespeare, and the fascination with the likeness. And also the question: was there a genuine portrait made of him while he was alive?”

The painting is known as the Chandos portrait, because it was once owned by the dukes of Chandos. It is small, just 55cm high, and historians say that both the artist’s technique, in oil on canvas, and the dress and appearance of the sitter, are consistent with English fashions of the early 1600s. The British NPG’s website says the portrait has “a good claim to have been painted from life”.

But the link to Shakespeare is tenuous, based on “tradition” rather than certainty. The picture supposedly was once owned by William Davenant, a theatre manager and playwright who also claimed to have been Shakespeare’s godson or illegitimate child. That connection was made in the early 1700s by George Vertue, who also attributed authorship of the painting to John Taylor, a member of the Worshipful Company of Painter-Stainers and, apparently, a friend of Shakespeare’s.

Questions about authenticity and whether a painting represents a true likeness go to the heart of portraiture as a genre and to the organising principle of portrait galleries, which almost peculiarly are a phenomenon of English-speaking countries. A second exhibition, a joint project between the National Gallery of Victoria and Canberra’s NPG, brings the matter of likeness to a head. Several of the artworks in the exhibition – called Who Are You: Australian Portraiture – have no objective resemblance to persons living or dead. In fact, the exhibition upends many of the received conventions of portraiture, as it was inherited from the Western art tradition and institutions such as the British portrait gallery.

By the time the British House of Lords established the portrait gallery in 1856, portraiture was part of the imperial project. Central to the new gallery were ideas developed and circulated by Thomas Carlyle about heroes and the representation of them. “Portraits are the candle by which we read history,” he wrote. The new gallery was not only a display of pictures but a hall of honour: a place to remember and reflect upon the great and the good.

To have your portrait hung in the NPG, Smith says, “you had to be an important or eminent person in society”.

“And we had this other very bizarre rule when we opened: apart from the ruling monarch, the sitter had to be dead for 10 years before they could be admitted,” she says.

Representation was everything. A portrait was symbolic of power, property and cultural potency. It was the link between a man’s record of achievements and his visible identity. No wonder such weight was given to the Chandos portrait and the belief that it depicted the greatest writer in the English language: by the Victorian period, the idea of a true likeness had taken on a quasi-religious significance.

“It’s quite religious and superstitious in a way,” Smith says. “If you have access to that (likeness), you have access to the thoughts, the values and beliefs. It’s why likenesses can become icons – they have some sort of talismanic power.”

Australia inherited the Western art tradition of portraiture and the formula of eminence established with the British portrait gallery. The Archibald Prize, first awarded in 1921, would be given for a portrait of a “man or woman distinguished in art, letters, science or politics”. The Australian NPG, when it opened in 2008, followed the British gallery’s convention of privileging the name of the sitter over the artist.

The Melbourne exhibition, Who Are You – it later will travel to Canberra – offers a fascinating counterpoint to the pictures coming from London. Unlike the Chandos portrait, and the desire to attach a face and body to the name of Shakespeare, some portraits in the Melbourne exhibition are so self-effacing as to be abstract. The show challenges many assumptions of what portraiture is, and what it purports to represent.

In a catalogue essay, titled Against Likeness, Penelope Grist asks whether representation is any longer a meaningful aspiration of portraiture, particularly in the age of photography. What would be portraiture’s potential if we made a leap beyond mere representation, and assumed that human beings, their inner selves, are essentially unknowable to others? “What happens when the simple, comfortable fiction of likeness gives way to an imaginary that embraces humanity in all its cryptic complexity?” she writes.

Who Are You – the show takes its title from a text-based work by Brook Andrew – is a large exhibition of about 200 works, taking in painted portraiture as well as photography, jewellery, sculpture, costume, ceramics and video. It includes some well-known images of recognisable people: John Brack’s self-portrait while shaving, William Dobell’s portrait of Helena Rubinstein, and Howard Arkley’s of Nick Cave.

But viewers will be challenged or bemused by the inclusion of artworks that resemble nothing like a human figure or face. Melbourne artist John Nixon, who died in 2020, is included with his painting titled Self Portrait (non-objective composition) (yellow cross). It is as the title says: a non-objective composition of a yellow cross on a black ground.

“The representation of one’s self does not have to be what someone sees in the mirror,” says NGV curator Beckett Rozenthals. “There is also an element of performance in self-representation, and what one chooses to reveal or conceal. If you think about John Nixon’s cross – where the artist’s body has been replaced with a cross, which the artist used as a motif throughout his career – self-observations can be purely abstract.”

Other works in the exhibition offer different interpretations of personal identity. It includes beautiful examples of Victorian mourning jewellery, encasing strands of the departed’s hair. James Lynch is represented by his punk outfit of bondage trousers, black leather jacket and chains.

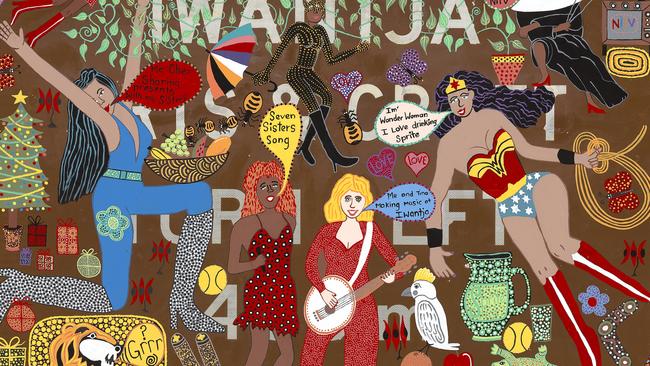

Kaylene Whiskey, in a new painting acquired by the NGV, has interpreted the Seven Sisters Song in a painting that includes pop-culture figures Whoopi Goldberg, Dolly Parton and Wonder Woman.

The show also sets up juxtapositions between the nominal status of individuals. Polly Borland’s 2002 photographic portrait of the Queen – the monarch is shown in a full-frontal pose against a gold background, in what could be either mugshot or icon – will be hung next to a photograph by Indigenous photographer Michael Riley of Maria, a woman of aristocratic bearing in a picture that uncomfortably recalls images from ethnographic surveys.

“The curators worked together to look at how we could reframe the portraiture genre, branching out from traditional modes to look at innovative and different approaches,” Rozenthals says. “It looks at the contrasts between the two collections, and at portraiture across media and time.”

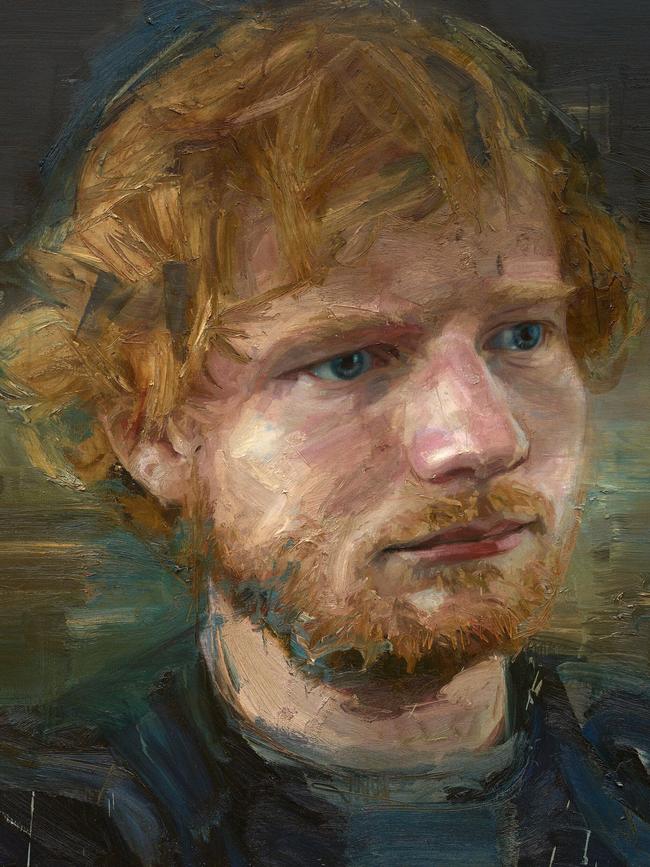

The Canberra exhibition, Shakespeare to Winehouse, has many more pictures than the Chandos portrait. From royalty and politics are portraits of Elizabeth I, Oliver Cromwell and Margaret Thatcher. From literature and the arts are Nell Gwyn, Dylan Thomas and Darcey Bussell. From pop culture are celebrated portraits of The Beatles, David Beckham and Ed Sheeran. Amy Winehouse is shown in a posthumous portrait by Marlene Dumas.

Thanks to the annual hoopla of the Archibald Prize, Australians have a near obsession with portraiture and are not shy in expressing opinions about it. The two exhibitions in Canberra and Melbourne offer examples of portraiture from across 450 years, and raise the inevitable question: Are we hung up about likeness, or can a portrait be something else?

Shakespeare to Winehouse: Icons from the National Portrait Gallery, London is at the National Portrait Gallery, Canberra, March 12-July 17. Who Are You: Australian Portraiture is at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, March 25-August 21, and at the NPG, Canberra, from October 1.