Journey to the edge of reason

VISUAL ARTS: Inner Worlds.. National Portrait Gallery, Canberra. Until July 24.

CONCEPTIONS of madness have a long and complex history, including ideas about how pathological states of insanity could be treated, and also more positive views of religious or poetic inspiration as benign forms of madness.

"Don't you realise," asks Socrates, with a characteristic combination of seriousness and irony, "that the greatest of goods come to us through madness?"

Inner Worlds, at the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra, is concerned more specifically with the modern psychoanalytical understanding of madness and other forms of mental disturbance, which goes back to the work of Freud a century ago in Vienna. The show is an intriguing though slightly disconcerting one that reminds one a little of the surrealist game of cadavre exquis, where someone starts a drawing, then passes it to a second person, folded so only the ends of the first section are visible.

Typically, the drawing may be a figure, where the first person does the head and shoulders, the second the torso, then a third, to whom the folded paper is passed, draws legs without knowing what kind of creature they are attached to. The surrealists were also fascinated by Sigmund Freud's study of the unconscious and the way it surfaces in the ostensibly random.

In Inner Worlds, we start with an introduction to the figures who brought psychoanalysis to Australia: John William Springthorpe, shown in his uniform as a lieutenant-colonel during World War I, and Roy Coupland Winn and Paul Greig Dane, both photographed in military uniform in 1915. What these opening images make clear, even without the accompanying text, is that it was the psychological devastation wrought on those who survived World War I that gave impetus to the medical study of the mind.

World War II gave further opportunities to witness the traumatic effects of battle, shelling and indeed of killing. A second generation of psychological pioneers includes H. Tasman Lovell, commemorated in a medal, and R.S. Ellery, associated with the Angry Penguins group and, after the war, Clara Lazar Geroe, in a painting by Judy Cassab (1965) and Janet Nield, again by Cassab (1973).

Then the paper is folded and we find ourselves before a collection of drawings by patients of another psychoanalyst, Eric Cunningham Dax; another fold and we have a mini-exhibition of Albert Tucker and Joy Hester; and a final one for an epilogue with Dale Frank, Anne Ferran and Mike Parr.

The drawings of the patients, selections from a vast archive, are interesting not so much for their aesthetic qualities as for their differences from what we would usually consider art.

It is not so much a matter of skill, although the works are childish in their level of competence, but that they are, perhaps more surprisingly, so unexpressive.

One of the prerequisites of expression is an element of detachment; an actor does not move us because he is overcome by emotion but because he knows how to feign, to construct the illusion of emotion. When a poet writes about real emotions, they are not only recollected in tranquillity, as William Wordsworth said, but consciously reconstituted in an artifice of words and rhythms, which is why, in John Donne's words, "grief brought to numbers cannot be so fierce".

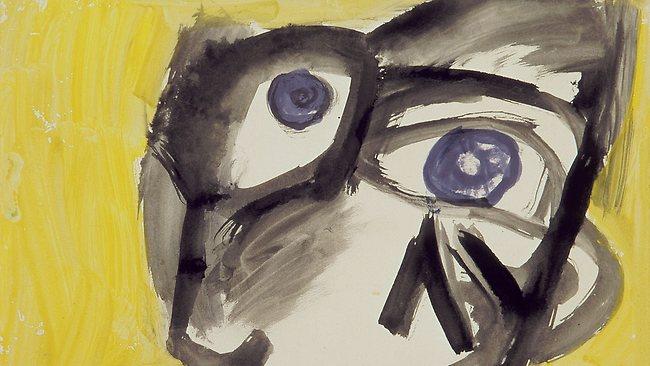

The works of these patients are not expressive because they cannot get outside their own feelings; they are frozen, pitifully obtuse and blank. The most aesthetically effective of them is a face, executed in dark wash, sinking to the bottom of the page and dissolving in clouds of black ink. It conveys a vivid impression of a certain state of mind but still painfully evokes the patient's state of mind rather than breaking free to become an aesthetic idea.

Neville Symington, a distinguished Sydney psychoanalyst and author, has suggested, if I understand him correctly, that narcissism is the ultimate "pattern of madness". As we move from the work of these patients to the pictures made by Tucker during the war and to his estranged wife Hester's series of hysterical eye-popping heads, we are dealing with two individuals who were not mad but were certainly narcissistic. Tucker's narcissism is palpable in the lack of sympathy he brings to his pictures of the mentally ill, while those that evoke his own mental state, such as the various fragmentary self-portraits and the hysterical cartoon The Possessed (1942), indulge his personal feelings to the full.

As for Hester, there surely has never been an Australian artist who combined such strident emoting with so little actual ability.

In the final room, there is a substantial series of self-portrait drypoints (1990) by Mike Parr, rather spoiled by the noisy video of his own later performance using these sheets. Repeated noise in exhibitions is disturbing to the sanity of viewers.