Intern nation

THE Enemy at Home is a moving reflection on the energy and ingenuity of the human spirit under very difficult conditions.

THE Enemy at Home is a remarkable exhibition in many ways: as a collection of grippingly immediate photographs, as documentation of an important moment in the history of Australia and, above all, as a moving reflection on the energy and ingenuity of the human spirit under very difficult conditions.

Often humorous on the surface, these images nonetheless leave us with the bitter aftertaste of injustice and stupidity on the part of the Australian authorities.

At the outbreak of the Great War, people of German origin made up the numerically greatest non-British part of the Australian population, and they tended to be educated and skilled, represented in all walks of life from academe and medicine to business, farming and viticulture, where they were pioneers of Australian winemaking.

Perhaps there were so many Germans in Australia partly because Germany never had an extensive overseas empire - it had existed as a unified nation only since 1870 - and several of the territories that the newly unified German Reich did acquire were in the Pacific area and in Australia's vicinity.

Another reason for German migration to Australia, easily forgotten in hindsight, was that the German states had long been natural allies of the British in their effort to contain the main continental superpower of early modern Europe, namely France. Even the royal family of Britain had been German since the accession of the Hanovers in the 18th century. The British and the Prussians had defeated Napoleon together at Waterloo. Throughout most of the 19th century the relationship seemed a natural one; but all that began to change as the new Germany grew into an increasingly aggressive and paranoid military power.

A rift soon developed between Britain and Germany, while Britain and its ancient enemy France, embittered and humiliated by spectacular defeat at the hands of Prussia in 1870-71, began to entertain friendlier relations. The Germans, meanwhile, bet on alliances with two doomed multi-ethnic states, the Austro-Hungarian and the Ottoman empires, while the French cultivated another fatally unstable regime, tsarist Russia.

Much of this old order would come crashing down in the demolition of the Great War, and completely new political configurations would arise throughout central Europe and the Middle East.

When the war broke out, Australia naturally joined in on behalf of the mother country, even though we had been an independent nation since the beginning of the century.

But this was a new kind of war, the global conflict of a new mass society: the first in which whole populations were induced to think of other peoples as subhuman barbarians. The Germans were parodied as Huns and presented in posters as bloodthirsty monsters yearning for world dominion, crushing women and children under their jackboots.

It is hard to know how much latent anti-German sentiment may have existed in Australia: as we have seen, there was no long history of hostility between Britain and Germany. On the other hand, Australia did have distinctive German communities, especially in South Australia and Queensland, and once the war began there seems to have been no shortage of organisations, from the British Medical Association to trade unions, willing to exploit xenophobia in the cause of self-interest.

In any case, it is clear that the Australian government whipped up anxieties about the loyalty of German-Australians to focus

the minds of the populace more clearly on the reality of a menace that could otherwise have seemed too far away to be urgently apprehended.

When war was declared, the crews of German merchant ships in Australian waters were interned as enemy aliens, to be joined by the officers and men of the light cruiser SMS Emden after it was captured by HMAS Sydney in 1914. Soldiers and civilian settlers taken prisoner in German Pacific territories were included as well, and then increasingly leaders of the Germanic population in Australia itself, with the aim of keeping others in their community in line.

Altogether, almost 7000 men out of a total of about 100,000 German-Australians were held in confinement during the war years.

Fortunately for our knowledge of the world of the camps, however, these detainees included a young photographer whose archive is the source of most of this exhibition. Paul Dubotzki, a Bavarian, had been the photographer for a scientific expedition to China in 1913 and had then travelled to Adelaide, where he was interned in 1915.

He took hundreds of pictures of life in the internment camps, which largely remained unknown until one of the two curators of the present exhibition, Nadine Helmi, saw some by chance at an exhibition at Trial Bay; she made contact with his family, who still live in his home town of Dorfen, and thus a wonderful collection of images was brought to light.

The Germans were first held in regional camps across the country, but after complaints of abuse were soon all moved to three centres in NSW. The largest, where about 6000 men were held, was at Holsworthy, where conditions were the most crowded and, especially at first, oppressive. Two other small camps were set up in the old jail facilities at Berrima and Trial Bay to house officers and men of higher social standing.

The exhibition includes a reconstruction of the cramped huts built for the detainees at Holsworthy, and photographs of the common latrines give a vivid idea not only of the primitive amenities but of the radical lack of privacy and personal space.

During the first couple of years, physical hardship was compounded by the authoritarian administration of the military and the depredations of a gang of criminals within the camp, known as the Black Hand. Finally, in May 1916, a group of sailors from the Emden and soldiers from the former garrison at Tsingtao, the German concession in China, formed an alternative association called the White Hand, rounded up the criminals and threw them over the barbed-wire fence.

A few months later, in the winter of 1916, the camp inmates went on strike against the military regime under which they were administered. The authorities gave in and granted the camps the right to effective self-management. From then on the communities developed their own elected administrations and provided their own internal policing; businesses and other social organisations began to flourish. Money was earned and invested in improved communal facilities.

This is the most fascinating aspect of the story: how a collection of men is torn from the social fabric to which they belong, deprived of their normal occupations and the resources to which they are accustomed, and yet how they rebuild a social world out of almost nothing.

The experience of detention must have been deeply disturbing in many ways, beginning with the brutal interruption of all one's habits and daily life, the anguish of separation from family, the humiliation for a respected member of society of finding himself suddenly treated like a common criminal; and then there was the limbo-like idleness, even stranger in a time of war - to be interned was to be safe, but no doubt to suffer guilt at the thought of the danger to which others were exposed.

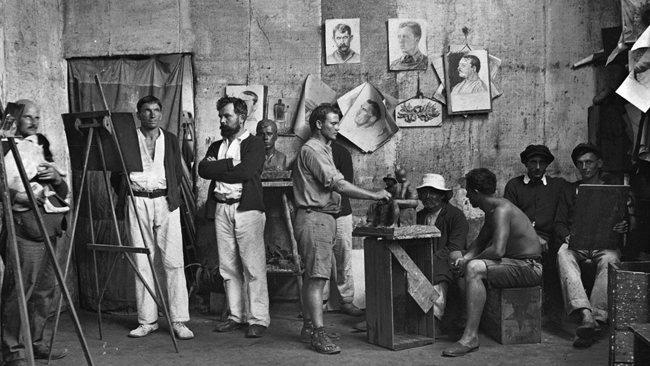

Yet these were not men to sit around feeling sorry for themselves; instead, they set about reconstituting a social fabric, a task clearly made somewhat easier by the fact they all came from a highly sophisticated and ordered society in the first place. They soon had canteens and cafes, barber shops and camp newspapers. Dubotzki set up a thriving photographic business.

They developed schools: apparently more than a dozen modern languages were taught, as well as Latin and ancient Greek. Peter Pringsheim of the University of Berlin gave lectures published after the war as Fluorescence and Phosphorescence in the Light of Recent Nuclear Theory. Most impressive of all was the establishment of a naval engineering school, which awarded diplomas recognised in post-war Germany.

Even more surprising, in a way, is how much fun they managed to have under the circumstances. The two smaller jails, in particular, offered opportunities to get out into the natural environment. At Trial Bay, inmates not only improved their living quarters but even built little huts along the beach, where they could go swimming and fishing the year round. There is even a picture of what used to be called a bathing machine - a changing hut on wheels - which seems more of a conceit than a necessity, especially as there were no women present.

At Berrima, they built cabins along the banks of the Wingecarribee River and constructed countless small boats for use in regattas. The locals were curious and often hostile at what seemed excessive luxury; indeed the place ended up, apparently, looking like a pleasure resort and was subject to attacks by vandals until the government declared it a prohibited military area.

Even at Holsworthy, though, the inmates built gymnasiums for physical exercise, and several striking photographs bear witness to the athletic prowess of the camp's athletic clubs. Theatres, too, were built and plays produced, even though the female roles had to be taken by men.

It is a story well worth recording and one that deserves more study. From a distance, it is like an allegory of social breakdown and recovery: initially, the crowding and confusion lead to a severe stressing of the social fabric, a weakening of the body politic, so to speak, of which criminals take advantage; then order is reasserted, the criminals are eliminated, responsibility is demanded and granted, and a social microcosm is restored.

To an outside observer, such resilience and enterprise, and even love of life in the face of traumatic disorientation, would seem proof enough that these people were an asset to our nation; unfortunately prejudice and self-interest prevailed, and most of them were deported back to the chaos of a defeated Germany, at a terrible cost in the suffering inflicted on families torn apart without compunction.

The Enemy at Home

Museum of Sydney, until September 11