He's not god, but he's got his groove back

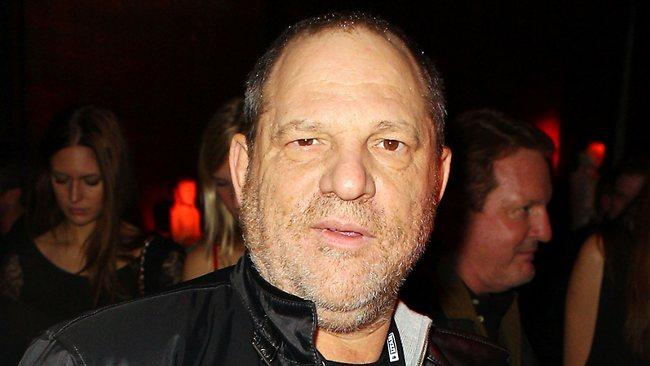

HARVEY Weinstein is once again making fiendishly good movies.

AFTER a spell in the cinematic wilderness, Hollywood's most talked-about producer is back.

Harvey Weinstein may have been crowned by Vanity Fair as "the last true impresario", but don't call him God.

"It's very nice when Meryl Streep calls you God," Weinstein, 59, tells The Times. "But then I get three emails from my three kids, all saying 'Hah!'. And then four hours later I have to do a TV chat show, where I appear next to a dog who almost poops on my leg. So then I know: I'm not God."

The anecdote relates to the Golden Globes earlier this month. Streep forgot her glasses when she went to accept the best actress in a drama award for her role as Margaret Thatcher in The Iron Lady, and her subsequent off-the-cuff address included the proclamation of Weinstein's divinity.

It was the latest chapter in what may become one of Hollywood's great comeback stories. Weinstein is behind The Iron Lady, The Artist and My Week with Marilyn. As they put it in Tinseltown, Harvey's got his groove back.

In 1979 he and his brother, Bob, founded Miramax Films and transformed the face of independent filmmaking. Their triumphs included Sex, Lies and Videotape, The Crying Game, Pulp Fiction, The English Patient, My Left Foot, Good Will Hunting, The Piano and Shakespeare in Love. In an 11-year stretch, they bagged 13 best-picture Oscar nominations.

Disney bought Miramax for $US60 million in 1993. The brothers ran it until 2005 when they left, acrimoniously, and raised $1 billion from Goldman Sachs and a handful of wealthy investors to found the Weinstein Company.

Weinstein envisaged building a media empire, but by 2009 he was drowning in debt and his hit machine was spluttering.

A theory emerged: Weinstein, the "Oscar King", had fallen out of love with making movies.

"That's 100 per cent accurate," he says. "I was looking after six or seven companies. And you couldn't have found a worse chief executive if you'd gone to central casting. It taught me to be humble. Now I stick to what I'm good at."

What he's good at is finding films that win critical acclaim and take lots of money. He backed The King's Speech, which cost $US15m and grossed $US386m. Of his current projects the most idiosyncratic is The Artist, a black-and-white, mostly silent film that Weinstein calls "a love letter to the movies". It is the year's unlikeliest hit. It may also be the most indicative of his way of working. He has a talent for picking movies that rivals neglect. The King's Speech was a hit, he notes, but "almost nobody" was interested in the script before it was released.

Speaking to The Times he is charming. But tales of an alternative "Bad Harvey" abound. It is said he can be foul-mouthed, arrogant and boorish. The vigour of his awards campaigns have upset some. This year the Academy Awards have clamped down on the amount of lobbying Oscars contenders can engage in, a sanction some say was designed to curb "the Harvey effect".

Almost everybody seems to agree, however, that nobody knows cinema better. "His knowledge of films is unrivalled," said Peter Bart, an industry veteran who helped to produce The Godfather.

He is also an anglophile. His wife is British fashion designer Georgina Chapman. In 2004 he was made a CBE for contributions to the British film industry. The latest project with a British theme is The Iron Lady, a movie he singles out as one of his most controversial.

His domestic situation seems to mirror Britain's reactions to it. His English mother-in-law disliked Thatcher. His English father-in-law worships her. He says chuckling: "The one thing they agreed on is that Meryl Streep is amazing."

THE TIMES