Hello, sunshine

A year or so earlier in England — he had fled with his family to escape the Franco-Prussian war — Monet encountered the paintings of JMW Turner and his atmospheric compositions of light, water and mist. In his own paintings of the Thames, Monet tried out similar effects, observing how fog and smoke changed the ambient light over the river and seemed to give texture to the air.

Now, back in Le Havre, he applied the insights of his London sojourn to the maritime landscape that was familiar from his youth. From his hotel room he painted the broad expanse of water, the ship masts and cranes along the horizon line, and the rising sun adding its aura to the misty grey. When he submitted the painting for exhibition he was asked to give it a title. Call it Impression, he said.

The picture belongs to the Musee Marmottan Monet, a small but elegant gallery in the 16th arrondissement of Paris that has, among other things, the world’s largest collection of Monet paintings. A special exhibition hall is given over entirely to him.

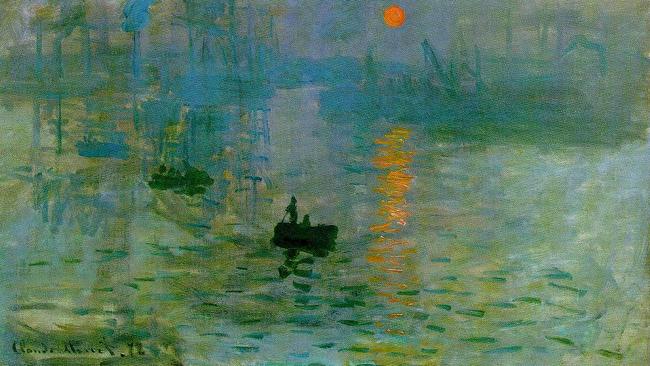

Impression: Sunrise is small in scale, especially when sized up with the large waterlily paintings nearby. You can see that Monet applied the paint quickly, giving the picture an almost sketch-like quality, and in some places the raw canvas shows through. The sun is a neat circle of tangerine. Slashes of orange and white are its reflection in the water. Looking at the picture, you have the impression — and it was indeed an impression that Monet wanted to make — of a moment captured in time.

This is the picture that gave its name to impressionism and is now among Monet’s best-known. When it comes to Canberra next month with a show of pictures from the Marmottan and other galleries, it will be the star exhibit. But for the first half of its existence Impression: Sunrise was hardly known at all. Early on, it was held in private collections and was not yet the subject of posters and greeting cards. Details about where and when Monet painted it were vague, and there was even confusion about what it represented: was it Impression: soleil levant or, as some records have it, soleil couchant?

“Impression: Sunrise was recorded as Impression: Sunset here until the 1950s,” says the Marmottan’s deputy director, Marianne Mathieu, as we stand looking at the picture. “No one knew precisely if it depicted a sunrise or a sunset …

“We want to tell the story of this painting because it had been forgotten for quite a long time and saved thanks to collectors.”

The day after visiting the Marmottan, I make the trip to Le Havre to see where Monet painted his early-morning harbour scene. The 8.37 leaves from Gare Saint-Lazare, the station that Monet painted as it was in the late 19th century, with its vast gabled roof and clouds of steam and smoke issuing from the locomotives. On the journey, I consider how much fossil fuels added to the atmospheric effects that Monet and others produced in their paintings, when they turned their gaze from the natural world and towards the rapidly modernising cities. London, Paris and Le Havre would not be quite as picturesque, in their painted versions, without carbon emissions and a blanket of smog.

A local art historian, Geraldine Lefebvre, meets me at the station and we drive the short distance to the harbour and the spot where Monet painted Impression: Sunrise. It looks nothing like the painting.

For starters, Le Havre was flattened by Allied bombs in September 1944 when the city and its strategic harbour were still held by the Germans. The harbour as Monet saw it in the early 1870s no longer exists. Instead of the hand-operated cranes and ship masts, there are warehouses, oil tanks, silos and a cruise terminal.

Second, on the April day I visit, there’s not a cloud in the sky. There’s none of the hazy atmosphere or dappled reflection that Monet translated on to canvas with almost calligraphic brushstrokes. The light is clear, bright and direct, and not at all impressionistic.

“When Monet came to Le Havre it was in November and the atmosphere was very misty, very foggy,” Lefebvre says. “And not only foggy because of the weather but because of the atmosphere of this industrial harbour. It’s smoke of the chimneys, smoke of the tugboats, smoke of industry. Monet was painting in one gesture — he did that to show a precise moment of the day, when the sun rises. He tried to keep the atmosphere and to put on the canvas all of the atmosphere of the harbour.”

At least one of the painting’s mysteries is easily solved. Monet painted Impression: Sunrise looking in the direction of the inner harbour and towards the rising sun. If he was instead painting a sunset, he would be looking the other way, out of the harbour and towards the sea. I make the mistake of calling the body of water to the west the English Channel.

“We call it La Manche,” Lefebvre gently corrects. “But you are right, this question was not hard … When you live in Le Havre, when you come to Le Havre, you understand immediately that it can’t be a sunset. Of course it is the sunrise because the sun is rising from the east.”

Monet was born in Paris in 1840 but when he was five the family moved to Le Havre and it’s where he spent his school years. Coming here, the visitor gains an understanding of the artist as a young man. It was in Le Havre that Monet, when he was a teenager, met local artist Eugene Boudin, who urged him to get out of the studio and paint among nature, en plein air. Lefebvre shows me the comfortable middle-class house where Monet lived, the steep headland where he probably scrambled around the rocks and scrub, and the pretty seaside spot where he painted another of his celebrated pictures, Garden at Sainte-Adresse, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

In 2014 the Marmottan marked its 80th anniversary and Mathieu was determined to unknot the puzzle of Impression: Sunrise — in particular the exact location and likely date of its composition. It was not known for certain in which year Monet painted the picture, only that it had to be after his return from England in late 1871, and before he showed it in Paris in 1874, in what became known to history as the first impressionist exhibition.

To find the spot where Monet painted Impression: Sunrise, Lefebvre and Mathieu consulted land registry maps, engravings and photographs that enabled them to form a picture of the harbour at Le Havre as it was.

A chimney stack that is billowing smoke in Monet’s picture was constructed in December 1871, confirming that the picture must have been painted after that date. He also depicts two cranes on the Quai Courbe — seen at the picture’s right — that were in place when the harbour was being expanded to allow for the passage of larger transatlantic ships.

Lefebvre concludes that Monet was painting from the opposite embankment, the Grand Quai, and that he was staying at the Hotel de l’Amiraute. He had a room with a view, so it was probably on the third or fourth floor, giving him a panorama of the harbour. (Novelist Stendhal had stayed in the same hotel several years before and described a similar scene: “the yellow-brown smoke of steamboats” and “sprays of white steam”.) The spot where Lefebvre and I have been standing is now called the Quai de Southampton, and on the site of the long-gone hotel is a row of shops and apartments.

The picture’s date was uncertain because although Monet signed it “72”, art dealer and historian Daniel Wildenstein, in his catalogue raisonne, argues it was among the pictures painted in 1873. An amazing combination of expertise was brought in to settle this and other discrepancies. The lock gate that can just be discerned in the middle of Impression: Sunrise is open, meaning that it must have been high tide when Monet painted the scene. Trade almanacs, historical tide charts and weather records narrowed the range of possible dates in 1872 and 73.

An astrophysicist from Texas State University, Donald Olson, analysed the sun’s passage in the morning sky as Monet depicted it. From these and other observations, it’s likely the painting was made on November 13, 1872, about 7.30am. Monet entered the picture in the first exhibition of the Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors and Engravers in Paris in 1874. Louis Leroy reviewed the show and was sniffy about Monet’s picture — its vague, trendy title and what he decided was Monet’s facile handling of paint.

“Wallpaper in its embryonic state is more finished than that seascape,” he declared. Yet Impression: Sunrise gave him a catchy, journalistic idea. When his critique appeared in Le Charivari under the headline “L’Exposition des impressionnistes”, he inaugurated one of the best-known brands in art.

The exhibition coming to Canberra will include important precursors to this art-historical moment and paintings by other artists who shared with Monet similar ideas about subject and technique. There are paintings of the harbour at Le Havre by Monet’s mentor Boudin, as well as by Turner; several knockout paintings by the English romantic have been lent by the Tate. The Marmottan is not only parting with Impression: Sunrise but other pictures that help tell the Monet story, including Pont de l’Europe, Gare Saint-Lazare, On the Beach at Trouville and paintings from his late waterlilies series. Works by his contemporaries including Morisot, Sisley and Whistler help fill out the picture.

The Marmottan’s Mathieu argues that impressionism was not a movement or a school. The artists we list conveniently under that rubric — such as Renoir, Degas and Pissarro — were too individualistic to be considered a cohesive group. “What is it to be an impressionist — who knows?” she says. “‘Impressionism’ is vague enough to leave them to be free.” Even so, the picture of Le Havre that Monet painted one autumn morning in 1872 gave its name to a style that, almost 150 years later, is beloved by gallery-goers around the world. Now, that’s called making an impression.

Monet: Impression Sunrise is at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, from June 7 to September 1. Matthew Westwood travelled to France with assistance from Art Exhibitions Australia.

Picture the harbour at Le Havre, the French coastal city and port near the mouth of the Seine. One late autumn morning in 1872, Claude Monet set his easel at the window of his hotel overlooking the port. He would have seen the masts of ships, perhaps some fishing boats, and construction work happening just across the water. He may have smiled at the sun on his face.