Great explorers

EXPERIMENTAL gentlemen was apparently what the ordinary seamen called the scientists and intellectuals who accompanied James Cook's great voyages.

EXPERIMENTAL gentlemen is an irresistible title for an exhibition. It was apparently what the ordinary seamen called the scientists and intellectuals such as Joseph Banks who accompanied James Cook's great voyages of exploration; the expression is redolent of an upstairs-downstairs social stratification, combined with the even more ancient assumption by downstairs that upstairs are slightly barmy.

The word experimental, at the end of the 18th century, was both highly charged with modern meanings and completely free of any associations with what later came to be called "experimental art". It referred specifically to the role of empirical research and verification in the new science. And this is the title that Henry Skerritt, who combines the careers of art historian and rock musician, has chosen for his exhibition drawn from the collection of mainly early Australian work given to the University of Melbourne by Russell Grimwade (1879-1955), together with funds for further acquisitions.

Grimwade was an interesting and distinguished man whose father Frederick and Alfred Felton were partners in the pharmaceutical firm Felton Grimwade; half of the latter's fortune had become the Felton Bequest, which essentially built the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria and is therefore by far the most important bequest in the history of Australian art.

Grimwade, chairman of the Felton Bequest committee from 1952, trained as a pharmacist and joined the family firm, but was also active in many areas of scientific research and philanthropy and was an early supporter of historical and natural conservation. He was evidently as much of an experimental gentleman as the artists and scientists referred to in the exhibition's title.

It is thus quite natural that we discover a beautiful wooden chest with drawers full of samples of gumnuts collected by Grimwade, or that one of the glass cabinets should contain a volume of his botanical photographs, An anthography of the eucalypts (1920), next to the monumental work of scholarship by Ferdinand von Mueller, Eucalyptographia: a descriptive atlas of the eucalypts of Australia and the adjoining islands (1883). The word eucalyptus, incidentally, being a Greek neologism ("well-hidden") lends itself to such learned and almost Borgesian linguistic play.

Perhaps it is this consonance of interests or perspective that gives a particular interest to the small but intriguing exhibition at Melbourne University, although credit must be given to Skerritt for assembling objects exactly as a curator should -- that is, in such a way that they speak to each other and make us see things we might otherwise not have noticed.

One of the appealing things about the exhibition, in fact, is that explanatory panels are kept to a minimum, and we are not beset by label texts that try to set us straight about how we should interpret things like the early images of Aborigines. It is a relief for the audience to be treated like grown-ups, able to form their own views and judgments. Headphones attached to the walls offer complementary material, including music relating to the experiences of early Australia and commentary by the curator.

But to return to the Aborigines, several important images reflect the diverse and changing ways they were perceived by the early explorers and colonists. The very first Europeans to encounter the Aborigines in the 17th century, such as William Dampier, were struck by their rudimentary material culture and lack of interest in trade. But already in the background a new idea was developing. The ancients, in whose mythology the earliest men had lived in a golden age, had also commented on the superior moral character of certain primitive peoples, and in the Renaissance Montaigne's celebrated essay on Brazilian cannibals (1580) pointed out that though these people were brutal and cruel, they were also courageous and held lies and treachery in contempt.

The expression "noble savage" may have come from Dryden's play The Conquest of Granada (1670):

I am as free as nature first made man,

Ere the base laws of servitude began,

When wild in woods the noble savage ran.

The idea, however, was given an unprecedented momentum by the publication of Jean-Jacques Rousseau's prize-winning essay, the Discours sur les sciences et les arts (1753), in which he denied that progress in the arts and sciences had made civilised peoples morally better than primitive ones. On the contrary, moderns were more likely to be enfeebled and corrupted by their physical and social environment.

Support for the idea of the noble savage came in 1755 from a perhaps unexpected quarter, when Johann Winckelmann, in his Reflections on the painting and sculpture of the Greeks, suggested that the American Indians could give us an idea of the health and vigour of the ancient Greeks, who lived so much of their lives outdoors, exercised their bodies and were altogether healthier than the weak and sickly moderns. To make such a link between the ancient founders of our tradition and the idealised native amounted to a radical critique of modern life.

Hence the importance of the Indians in the neo-classical painting of Benjamin West, for example, and hence too, Cook's characterisation of the Aborigines, for the first time, in terms that explicitly recall the myth of the golden age: "The Natives of New Holland in a Tranquillity which is not disturb'd by the Inequality of Condition: the Earth and sea of their own accord furnish them with all things necessary for Life."

The very earliest images of the Aborigines are informed by such ideas, so different from those that would later prevail. The most famous of all, perhaps, is the engraving by William Blake after a drawing by Governor Richard Gidley King, which was published in John Hunter's An Historical journal of the transactions at Port Jackson and Norfolk Island (1793).

Blake has made the features of the family -- husband, wife and son -- rather more European than the original drawing, so that there is greater emphasis on the universal idea of the noble savage rather than on the specificity and difference of ethnographic observation. Confronted by figures who are different from us only in the colour of their skin and their nakedness, the viewer is made to ask, with Cook, whether the things they lack and we possess are not superfluities.

Blake's engraving evidently made an impression. Joseph Lycett's Views in Australia (1824-25) lies open at the page displaying "A distant view of Sydney from the lighthouse at South Head", and in the lower left of the foreground, we recognise the same family group, only now, and perhaps significantly, walking out of the composition.

The noble savage model gradually gave way to a combination of practical and intellectual developments. In the world of ideas, scientific discoveries about evolution and genetics raised for the first time speculation about the differences between races, which is quite different from the question of whether peoples, for any number of reasons, have or have not attained a given standard of cultural and technical development.

It became widely assumed, even by sympathetic observers, that the Aborigines were a race doomed to extinction. At the same time, social realities including tensions and violence, killings and counter-killings, undermined earlier idealistic conceptions. And the behaviour of drunken natives on the fringes of colonial society, satirised by S.T. Gill in the lithograph Native dignity (1855) reinforced growing prejudice, as we see from the respectable gentleman in the background who looks askance at the couple who are the subject of the print, while his daughter simply averts her gaze.

A very different perspective on Aboriginal life, incidentally, was provided by the fine black and white photographs of Ricky Maynard, shown concurrently at the Ian Potter but just closed. Maynard had many strong portraits, but his most memorable images were landscapes; sometimes places with particular and even painful historical associations, but more generally images of land that seem to resonate with a quieter and more perennial significance.

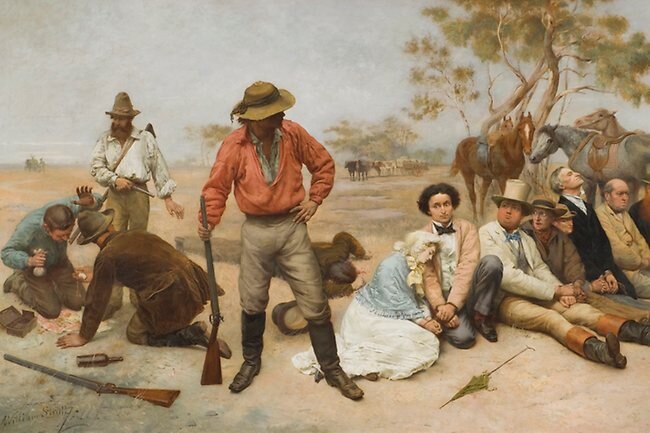

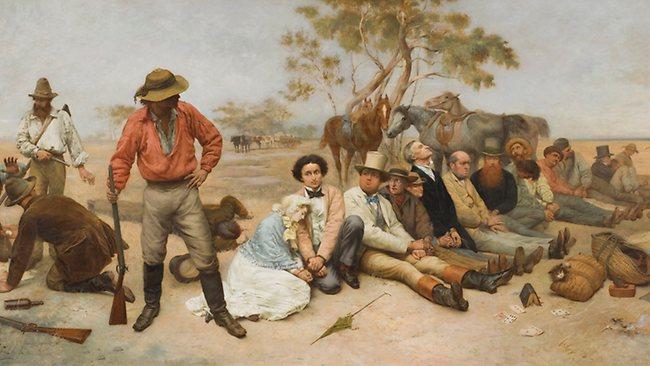

Another aspect of the social reality of colonial life is dealt with in a rare and important example of colonial history painting, William Strutt's Bushrangers, Victoria, Australia, 1852 (1887), a picture which makes a wonderful contrast, both in its painterly style and its manner of depicting the subject, with Tom Roberts's famous Bailed up (1895; revised 1927).

Strutt was the first painter to come to this country with a full academic training as a figure painter. Most of our early artists -- and understandably, most of those who travelled around the new world in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, painting pictures of the Americas, Africa, India and Australasia -- were trained as landscape specialists.

Landscape painters had generally not studied figure drawing to any advanced level, as they only needed to be capable of animating their landscapes with the small figures sometimes called staffage. Strutt was well-trained, but unfortunately he was also a rather mediocre artist. His most famous work is Black Thursday, February 6th 1851, painted in 1864, which was the centerpiece of last year's Bushfire Australia exhibition at the Tarra Warra Museum of Art. Here once again Strutt includes a date within the title, alluding to the time he was in Australia (1850-62) and implicitly suggesting that he is a witness to historical events, while also situating these events well in the past.

Unlike Roberts' strangely desultory hold-up, where no one seems too alarmed or even in a hurry, Strutt evokes a very serious event in which one of the passengers lies dead, while the remainder sit on the ground with their wrists bound, in various states of anger, misery or despair. Expression was the heart of the history painting tradition, but here Strutt falls into the academic reduction of expression to the psychology of individuals, manifested in facial grimaces and often exaggerated into masks that verge on caricature.

Far from bushrangers and even from Australia, yet hanging next to Strutt in the exhibition, is an attractive painting by William Glover. As Skerritt points out, this son of John Glover is a mysterious figure documented as having painted and exhibited but whose pictures have either been lost or misattributed. This one, a recent acquisition, has just been cleaned and is presented here for the first time.

It is an idyllic landscape in the tradition of Claude, very close to similar pictures by Glover himself. The subject could be a Flight into Egypt (the columns of the temple are Egyptian in style), except that the figure who should be Joseph seems too young. Perhaps this simply reflects the artist's lack of references as he worked, presumably, in Van Diemen's Land; a poignant reminder of how far he had travelled to this new land, and of his distance from the centre.

Experimental gentlemen

Ian Potter Museum, University of Melbourne, untio September 25