Easter’s drama powered our culture’s greatest story

This is the great story of our culture and its power is still part of us however far we have drifted or must drift.

It’s from one of the great Bob Dylan songs: “When you’re lost in the rain in Juarez and it’s Eastertime too. And your gravity fails and negativity don’t pull you through.” Easter naturally associates with the loss of gravity and the invocation of negativity. It is the most solemn time in our Christian culture’s calendar, encompassing the stark tragedy of Good Friday, the day God died, then after two days of darkness the blinding light of the resurrection. Christ is risen, one voice says, and the reply comes like clockwork: he is risen indeed.

Easter is a time for sorrow and new life, so we make it coincide with ancient festivals – pagan ones, but so what? We associate it with the son of man who walks from the tomb: the eggs, the chocolate, the love fix it gives.

But this is the great story of our culture and its power is still part of us however far we have drifted or must drift. You can gorge yourself on fish and chips and hot cross buns or eat barramundi with Beerenauslese white and still know Good Friday is a day of blood, the day when we took Christ’s life.

But Easter as we have kept it up is a complex exercise in counterpoint and tonal shifts.

We can follow the different accounts of the Passion. Luke has a special human quality. It is in his account that we get the good thief who is crucified alongside Jesus and says to him, “Lord, remember me when you come into your kingdom. And Jesus said unto him, Truly I say to thee. This day shalt thou be with me in paradise.”

Mark, according to tradition, was a very young man when he was Jesus’s apostle and he gives us the two great commandants: “And thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind, and with all thy strength: this is the first commandment. / And the second is like, namely this, Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself. There is none other commandment greater than these.”

An easy way into Mark’s gospel is that fine actor Alec McCowen who reads it with an intense feeling for its drama and power, whereas the versions of the whole of the New Testament by James Earl Jones and Gregory Peck use their respectively beautiful voices as if they were reading in church. The Lion King doesn’t have the vibrancy of McCowen.

But the different interpretations of the Easter story – in art, music and drama – are endless.

The great Italian filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini’s The Gospel According to St Matthew (1964) has the uncanny look of a neorealist documentary. It doesn’t have an ordinary script, it has the words Matthew reports to us, and the wobbling cameras and the black-and-white cinematography add to the weird sense that we’re looking at something that happened.

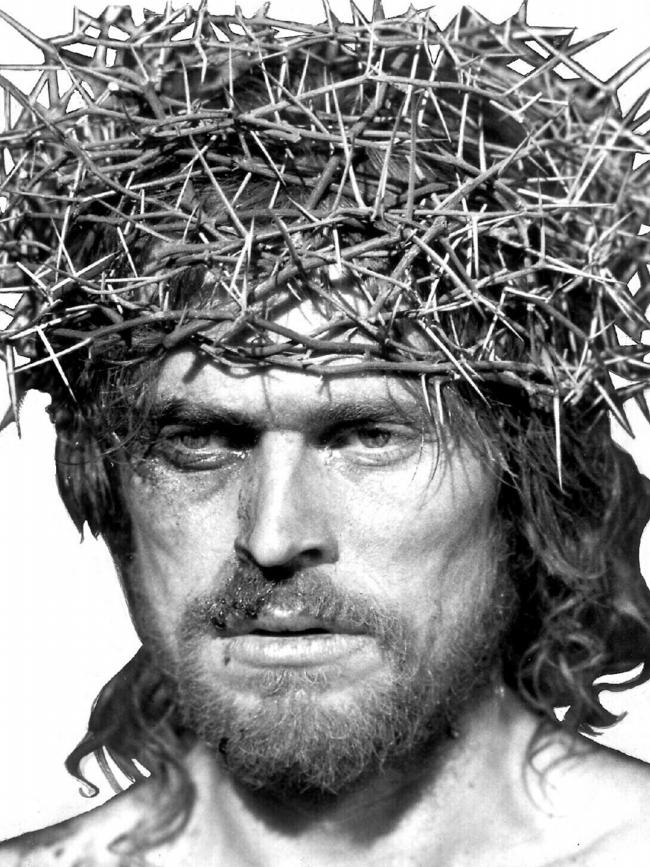

This is not to deny the power of Swedish actor Max von Sydow in The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965) or Willem Dafoe in The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), which dramatises Nikos Kazantzakis’s 1948 novel Christ Recrucified. Then there’s the bizarre reconstruction of Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ (2004) in which Gibson had the scriptural dialogue translated back into Aramaic – the language Jesus would primarily have spoken – even though the gospels are in the Koine Greek that was the language of the Roman Empire.

If you want a challenging literary dramatisation of Christ’s Passion listen to the BBC’s 1941 radio version of The Man Born to Be King in which Dorothy Sayers, the creator of aristocratic detective Lord Peter Wimsey and translator of Dante, tries her hand at dramatising the gospel story with Robert Speaight (who recorded TS Eliot’s poetry with considerable suavity and some beauty) as the Messiah.

Sayers – who certainly had the gift of tongues – is not interested in a grandiloquent version of Jesus’ life. The dialogue she gives him is much closer to the language of recent translations of the Bible. It’s plain, sometimes clumsily demotic: it all brings to mind the great authority on the Dead Sea scrolls, Steven McKenzie, who used to say to his students translating scripture, “None of your Shakespeare here.”

On the other hand, Sayers’s introductions to each of her radio plays are dazzlingly bright. She paints a convincing portrait of a Roman Empire – none too wonderful but parallel to the British Empire, which was far from secure in its dominions. It is one of the most brilliant discussions about it.

The St Matthew Passion of Bach is the work of one of the greatest artists who ever lived and so is his St John Passion. The standard contemporary accounts of the Bach passions are by John Eliot Gardiner and he is rightly applauded for the way he has reconfigured the baroque Bach without the romantic accretions.

Then there is the Otto Klemperer version of the St Matthew, which is incomparable and confounds all doctrine and dogma: yes, Klemperer is the conductor who makes The Magic Flute sound like Beethoven but that kind of breath and grandeur is there with an absolute magnificence in his St Matthew. Peter Pears as the Evangelist, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau as Jesus, Christa Ludwig in the contralto role and Elisabeth Schwarzkopf doing the soprano, with Walter Berry doing the bass and Nicolai Gedda the tenor. It is an extraordinary cast and Klemperer makes anyone else sound a bit swift and light.

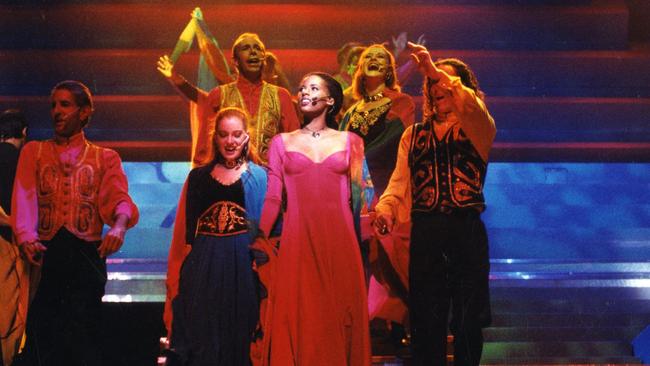

The Passion story is powerful in the widest variety of retellings. Jesus Christ Superstar (which was first a 1971 musical, then a 1973 film) includes one of the great Andrew Lloyd Webber songs, Mary Magdalene’s I Don’t Know How to Love Him. There is the beauty of the melody and the wistful wonderment of Tim Rice’s lyrics: “And I’ve had so many men before / In very many ways he’s just one more.” Knowing how it can be possible to love him is the enigma for every believer and seeker.

We identify Mary Magdalene with the woman of whom much is forgiven because she has loved much. When Jesus comes out of the tomb he meets her and she doesn’t recognise him. He says to her: Noli me tangere – touch me not. Titian did the painting of Noli Me Tangere (Christ Appearing to the Magdalene) at the height of his astounding powers.

Matthias Grunewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece terrified in the 19th century – including as seasoned a beholder of suffering as Dostoyevsky – because it presented an image of the Lord as palpably dead, dead as a consequence of torture and agony, a terrible thing to contemplate.

That was also true of Grunewald’s Small Crucifixion, which emphasises the death,

overpoweringly but with a bit less of the detail of slaughter. Then there is his complementary image of the resurrection. Among abundant images of Christ crucified and resurrected are frescoes such as Masaccio’s image of Christ on the cross with God the Father behind him. Sublimity is the word people reach for with Piero della Francesca’s The Resurrection.

When it comes to the culture, Christians have the immense benefit of so much art, music and literature created in the shadow of the world of this iconography, this belief system. That in no way lessens the faces of the great Buddha, let alone all that glory that was Greece and the grandeur that was Rome (that is a different part of any Western heritage).

While Easter in its Good Friday aspect is the most sombre thing around, we should not be too solemn. That one-time Jesuit, Peter Levi, a man of great wit and style as well as being professor of poetry at Oxford, at one stage wrote a bit of doggerel that perhaps only someone who had been a person of the cloth could get away with. “The lads of course arrived too late / Still for a little fee / Christ being crucified / They chopped down the tree.”

In his great panegyric for that adoptively Welsh poet David Jones, Levi noted Jones thought there were a lot of people in the church who didn’t realise they were in it. Our civilisation is up to its neck in it.

This doesn’t betoken a superiority to the Tang poetry or painting of China; rather, it should heighten our sense of the value of the Bhagavad Gita, the Upanishads and the Rubaiyat.

But let’s not minimise the power and the glory; it is, after all, one of the greatest stories ever told. There is a novel by John Steinbeck, The Winter of Our Discontent (1961) where the main character is haunted by the crucifixion; that old polymath (American literary critic and essayist) George Steiner used to say if he could have anyone in history to dinner he would invite Homer, Shakespeare and Jesus Christ because he wanted to know if they had existed.

Think of John Donne writing A Hymn to God the Father:

“I have a sin of fear, that when I have spun

“My last thread, I shall perish on the shore;

“But swear by thyself, that at my death thy Son

“Shall shine as he shines now, and heretofore;

“And, having done that, thou hast done;

“ I fear no more.”

When Donne wrote “For whom the bells tolls, It tolls for thee”, he wrote from the heart of a world full of glamour and terror. He was a man of the Renaissance, “a great visitor of ladies, a great frequenter of plays”. But he was also a priest and a man with a bravura sense of drama who understood the terrible times in which he lived and the democracy of spiritual difficulty.

Someone I was close to said once that he loved Easter because you didn’t have to see anyone.

That’s true but still they come to the Lutheran churches that nourished Bach, to the Roman churches that licensed the art of the Renaissance and to Hillsong where they clap and wonder and know they are one with folk who know how to believe.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout