Easter: The power and the passion

If you’re in any doubt about Easter having claims on your attention culturally, regardless of what you believe or don’t believe, look at the music and the art.

The haunting and hilarious novel The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov – who was born in Ukraine in 1891 and wrote one of the greatest masterpieces in 20th-century Russian literature – is a book to read over an Easter in a troubled time.

It begins with two men, one an editor, the other a writer (both of them hacks), discussing the novel the writer has written about Jesus. The editor is appalled because the story is so vivid and believable, when he knows it’s all a preposterous concoction.

Then a strange figure with eyes of different colours appears – he exhibits a passing resemblance (it sends a shiver down the spine and is very funny, too) to the Devil.

He purports to be a professor. There is a foreign accent but it vanishes as he takes up the story and begins: “Early in the morning on the fourteenth of the spring month of Nisan the Procurator of Judaea, Pontius Pilate, in a white clock lined with blood red …”

This is how the first chapter ends and the next, chapter two, titled Pontius Pilate, is set in Jerusalem. It starts with those exact same words: “Early in the morning on the fourteenth of the spring month …” Oh yes, and there’s also a huge black cat stalking around.

The Master and Margarita is dazzlingly unpredictable, very funny, very black. An Easter variation that will take your breath away and give you a shock of recognition if you read it long ago.

Pontius Pilate is one way into the story on which we have built so much of our civilisation, the story of a man who was God who came to save the world by redeeming it from the iniquities to which it seemed eternally wedded.

Pilate is no better than he should be; he washed his hands and declared, “I am innocent of the death of this just person,” though he knew he was not. But he is, for all that, the master of the great one-liner. “Am I a Jew?” he says, with patrician Roman disdain to this Nazarene nuisance. “What is truth?” he asked him, wondering now. Was he joking at this point as Francis Bacon, the old Renaissance wise guy, suggested (“jesting Pilate who would not stay for an answer”)? Yet a moment later he says: “I find in him no fault at all.”

And Jesus’ answer about truth would scare the eagles from the sky, however Roman they were: “Thou sayest that I am a king, to this end was I born, to this cause came I into the world, that I should bear witness unto the truth. Everyone that is of the truth heareth my voice.”

Pilate has him scourged, they put the crown of thorns on his head, and Pilate says – to use the Latin of St Jerome’s Vulgate translation – “Ecce homo” (Behold the man).

Later he tries the trick of appealing to the people on the grounds of the palpable superiority of this fellow who is supposedly a felon: “Behold your king,” he cries. They cry back to him the crushing words, “We have no king but Caesar.” So what does Pilate do? He makes a verbal gesture and an impotent one that has a certain snapping verbal power: “And Pilate wrote a title and put it on the cross and the writing was Jesus of Nazareth, the King of the Jews … and it was written in Hebrew and Greek and Latin.”

The chief priests tell him he should say Jesus claimed to be the king of the Jews and Pilate comes right back at them, again to give the Latin: “Quod scripsi, scripsi” (What I have written, I have written).

The Easter story begins with Palm Sunday, the triumphant entrance into Jerusalem, the cries of Hosanna, the welcoming crowd. It’s a glimpse of the triumph that might reign forever but soon it’s cut short. According to tradition we remember the denouement of the Passion: the agony in the Garden of Gethsemane, the accusations of blasphemy, the false judgment, the judicial murder. There are the preparations. The woman washes his feet with ointment and the disciples say the cost of it would have fed the poor. “The poor are always with you. I am not,” Jesus says, and insists on washing their feet. He tells them in his father’s house there are many mansions. There is also that extraordinary voice prophesying now about the horrors of war and the abomination of desolation.

Would there be any satisfaction, as you saw your children ploughed down in Ukraine, to read the words of the son of God?

To remember that on the way to the cross, meeting the gaze of the women who weep for him, Jesus says, “Daughters of Jerusalem weep not for me, weep for yourselves and for your children. Behold the days are coming in which they shall say blessed are the barren and the wombs which never bare and the paps that never gave suck. Then shall they begin to say to the mountains, Fall on us: and to the hills, Cover us. For if they do these things in a green tree what shall be done in the dry?” This seems to be the most tragic possible vision.

This ghastly Good Friday premonition tallies too with the great cry from the cross when Jesus says: “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” It is a terrible cry to come from the man who is God – it represents the vastness of the experience of despair.

It is, of course, quotation. It includes all the tragic sense of the desolation, of bereftness that runs through all the dark and dazzling mood shifts of the Psalms of the Hebrew Bible that Christ knew like the back of his hand, that sense of looking up into the hills, “From whence cometh my help?”, and at the same time the De Profundis (out of the depths I cry). There is all the rage and all the pain in the Psalms, some of which we hear echoed in the vengeance for which people cry in Ukraine.

One of the greatest of the Psalms, “By the rivers of Babylon”, includes this sort of horrific yearning for revenge even though it has one of the most beautiful lines in the whole of the Bible, Old Testament and New, Hebrew or Christian: “Jerusalem, if I forget thee, may my right hand lose her cunning.”

And it’s in St Luke’s Gospel we hear Jesus say, “Father, forgive them, they know not what they do.”

It’s in Luke, too, that we have what Catholic Cardinal George Pell in his prison journals says is one of the most moving and consoling moments in the whole story.

One of the thieves crucified with Jesus says, “Remember me, Lord, when you come into your kingdom.” And Jesus replies, “I tell you this night you will be with me in Paradise.” And he calls out: “Father into your hands I commend my spirit.”

This is the consummatum est. It’s all over. “It’s finished,” says the son of man, the son of God. All but the moment when the character in radiant white, shining like an angel because that’s what he is, tells Mary Magdalene he’s gone from the tomb. Then she meets him and doesn’t recognise him until he speaks, “Noli me tangere” (touch me not), and she calls him “Rabboni, which is to say, Master”.

What were those words that Tim Rice gave to Andrew Lloyd Webber to set to music? “I’ve had so many men before, in many different ways. He’s just one more.”

There are a thousand ways of commemorating Easter. Think of the great Bach Passions, the St John and the St Matthew, and the recording of the version of the St John by the great 20th-century composer Benjamin Britten with his partner Peter Pears singing the role of the Evangelist.

The whole thing in English so that the opening word, Herr, in the uncanny Herr unser Herrscher, is translated cunningly and felicitously as Sire. As The New Yorker music critic Alex Ross wrote: “When the upper voices reach ‘Herrscher’, you feel this is the scene at Golgotha of an emancipated body raised on the Cross, nails being driven in one by one, blood trickling down, a murmuring crowd below. It goes on for nine or ten minutes, in an irresistible sombre rhythm, a dance of death, that all must join.”

In some ways the greatest (uncannily great) singing of the Passion figures was recorded in the 1960s with Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau an incomparable Jesus. But this year we have had the third recording of the great John Eliot Gardiner’s St John Passion, which some believe eclipses the other two.

If you’re in any doubt about Easter having claims on your attention culturally, regardless of what you do or don’t believe, look at the music and the art and, as you do so, note the way they edge into something like a religious perspective.

The New Yorker art critic Peter Schjeldahl is a man whose apparent cynicism can make you laugh aloud, but he says Piero della Francesca, who did the great Resurrection of Christ – which Aldous Huxley referred to as the best picture in the world – gave him an experience that “in another age … might have made me consider entering a monastery. Instead, I became an art critic.”

In other words, any atheists may have to watch themselves if they submit to the art and music of Easter or the worlds they animate.

During World War II, Dorothy L. Sayers, who was most famous for creating that absurd toff of a detective Lord Peter Wimsey, and who went on to do a dexterous translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy in terza rima verse, did a set of radio plays about the life of Christ called The Man Born to Be King.

Sayers’s Jesus was played by Robert Speaight, who played Thomas More in the 1962 Australian production of A Man for All Seasons. Sayers wasn’t interested in the traditional diction of biblical language that Pier Paolo Pasolini used in his masterpiece, The Gospel According to St Matthew, dedicated to Pope John XXIII; still less in Jesus hooking up with Mary Magdalene as Willem Dafoe does in Martin Scorsese’s film of Nikos Kazantzakis’s The Last Temptation of Christ.

Sayers was a true literalist of the imagination, though one of intellectual brilliance in her Anglo-Catholic way. She believed Jesus was God. “This story of the life and murder and the resurrection of God-in-man is not only the symbol of the epitome of the relations between God and man; it is also a series of events that took place at a particular point in time … God was executed by people painfully like us, in a society very similar to our own in the over-ripeness of the most splendid and sophisticated Empire the world has ever seen,” she said.

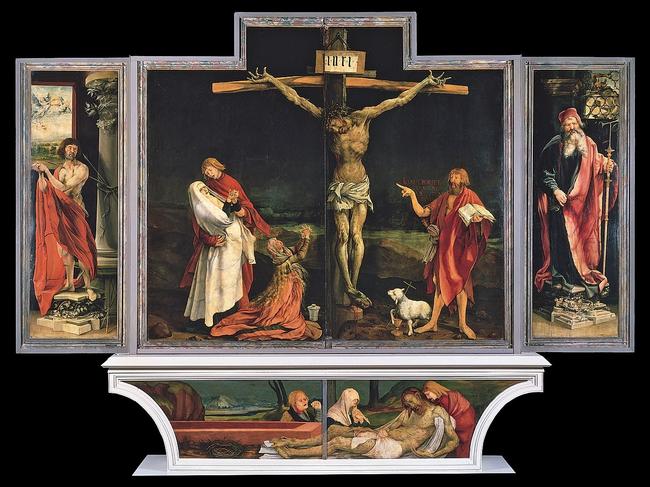

The paintings compel an assent even if in your unbelief it has to be a qualified one. Think of the rocky loneliness of Giovanni Bellini’s Agony in the Garden or the way Caravaggio, that master of the drama of painting, has a beardless youth of a Christ in his post-resurrection Supper at Emmaus. Is there a calmer and more meditative image of Christ on the cross than the great Diego Velazquez? Is there a more starkly ghastly atrocity of a crucifixion than Matthias Grunewald’s from the Isenheim altarpiece? Or a more dramatically focused and monolithic painting than Giotto’s The Kiss of Judas or one more fluent and luminous than Titian’s Noli me Tangere in which the Magdalen and the Master seem to glide into each other?

And yes, Schjeldahl is right, Piero’s Resurrection of Christ seems to instantiate the faith it carries with such absolute poise that it’s a wonder we haven’t all been driven into monasteries.

May the tragic power of Easter and its supreme hope sustain the afflicted people of Ukraine who in the person of Bulgakov produced one of the greatest and darkest fantasias on this theme.

May it sustain us all.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout