Dreams of landscape reimagined

A partnership between artist Christo and fellow refugee John Kaldor in Sydney changed Australians’ worldview for good.

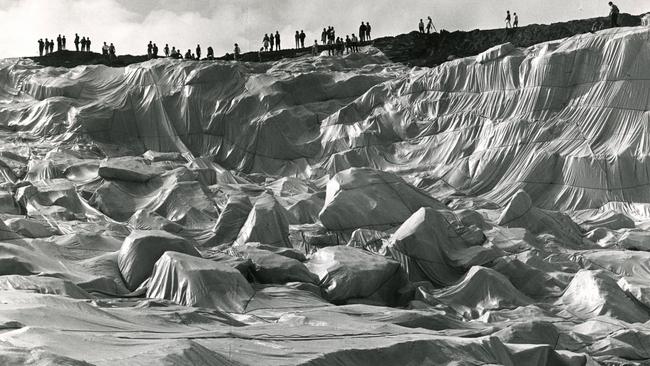

Christo’s giant packages of industrial fabric and rope have caused millions of people worldwide to wonder what it all means, but for the artist the motivation to create temporary monuments such as Wrapped Coast and Wrapped Reichstag can be summed up in a single word. Freedom.

Barely a decade before he and his partner, Jeanne-Claude, land in Sydney to cover 2.4km of sandstone coastline at Little Bay, Christo is a refugee fleeing from Eastern Europe. He settles first in Paris, then in New York, and starts devising ever more ambitious — some may think insane — ideas for public art.

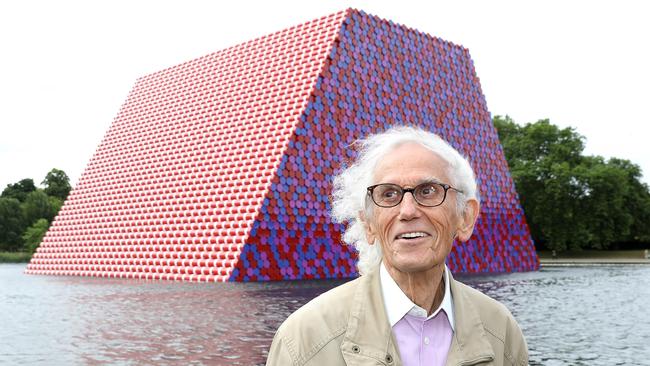

In the years that follow, he’ll wrap the Pont Neuf bridge in Paris, surround islands in Florida with pink polypropylene, build a floating pedestrian bridge on an Italian lake, and erect a mastaba of 7506 oil barrels in London’s Hyde Park. Next year he’ll return to Paris to wrap the Arc de Triomphe, fulfilling a long-held dream. As with all his projects, he will finance it himself. But why?

“You have to understand who I am,” he says via Skype from his studio in New York.

“I was born behind the Iron Curtain in a small country called Bulgaria. I was oppressed by the huge communist regime. I am also Czech — one-quarter Czech — and I escaped from the Soviet Bloc, from Czechoslovakia, when I was visiting my relatives, to the West in 1957 when I was 21 years old …

“I escaped only to be a free artist. And I will not give one millimetre of my freedom for anything. Anything. I do the things we like to do, not always when we would like to do them, and we fail to get many permissions, but it all comes from our idea, our desire, to do the things we like to do. I will not change, I am 84, I am still doing the things I like to do. Totally free. It’s my money, it’s my decision.”

Christo is a highly engaging conversationalist, and for the half-hour of this interview, he speaks in an almost constant state of excitement.

On the Skype video, I can see he is wearing a striped blue business shirt, and when he leans forward towards the camera, as he often does, I have a view of the top of his head, radiating wiry grey curls that have been described, not unreasonably, as Einsteinian.

He is speaking on the 50th anniversary of Wrapped Coast in Sydney in 1969. It was not the first of his and Jeanne-Claude’s major wrappings (in simultaneous projects in 1968, Christo wrapped the Kunsthalle in Bern, and Jeanne-Claude monuments in Spoleto); or the most controversial of their projects (that would be Wrapped Reichstag, or The Umbrellas); or the most prolonged (approval for The Gates in New York took 26 years).

But Wrapped Coast — involving 95,600sq m of environmental fabric, secured with 56km of rope — galvanised Sydney, opened the eyes of thousands to the idea of environmental art, and changed the lives of many, not least John Kaldor, who had brought Christo and Jeanne-Claude to Australia.

As Kaldor recalls the story, in 1968 he had seen photographs of another of Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s projects, 5600cu m Package — it looked like a giant inflatable sausage, installed at Documenta IV in Germany — and approached them in New York about the possibility of doing something in Australia, perhaps an exhibition or a lecture. He met them at their studio, where Christo still lives and works, and shared a lunch of stale sandwiches.

“Christo said: ‘No, I don’t want to lecture, I don’t want to do an exhibition — I want you to find a coastline to wrap’,” Kaldor recalls. “I took that seriously, and it literally changed my life.”

Christo and Kaldor are roughly the same age — Christo is a year older — and both were post-war refugees from Eastern Europe (Kaldor from Hungary). Christo, Jeanne-Claude and Kaldor were in their early 30s when they embarked on the scheme of wrapping the Sydney coastline, and remain firm friends.

When Kaldor married Melbourne businesswoman and arts patron Naomi Milgrom, Christo and Jeanne-Claude were guests at the wedding. (Jeanne-Claude, whose birthday is the same date as Christo’s, died in November 2009, at age 74.)

Wrapped Coast may have remained in the too-hard basket had Kaldor not persuaded the administrator of Prince Henry Hospital to let him have a piece of Little Bay. “The project of the coastline — they are not difficult projects technologically, it’s not like building a skyscraper,” Christo says. “The greatest luck is that John discovered this incredible, marvellous site, simply beautiful, Little Bay, very close to the international airport and Prince Henry Hospital. That was the greatest luck, that the project was so close to Sydney.”

Thus was Kaldor Public Art Projects born 50 years ago. An anniversary exhibition called Making Art Public opens this week at the Art Gallery of NSW, featuring photographs, videos, documents, correspondence, artefacts and in some cases partial recreations of the 34 projects assembled during the past half-century. Kaldor prefers not to call it a retrospective — “I didn’t want something that is static and dry,” he says — and for this reason he has invited an artist to produce it, as if it were another of the public art projects.

Britain’s Michael Landy was the artist of project 24 in 2011, Acts of Kindness, and he has returned to create Making Art Public (dubbed project 35).

I have joined him for a guided tour of the exhibition-in-making as it is being installed.

It has been devised as a series of walk-in boxes, each housing one of the projects. In one box is a sample of Gregor Schneider’s 21 Beach Cells, with a wire cage similar to those installed on Bondi Beach in 2007. Another box has no entry but from it emanates the sound of Gilbert and George singing: they were the third project in 1973. Jeff Koons’s Puppy from 1995 is represented with a bed of plastic flowers, and Jonathan Jones’s barrangal dyara (skin and bones) from 2016 is remembered with a bed of Aboriginal shields.

Most of the Kaldor projects were temporary and do not exist except in documentary form. To prepare the exhibition, Landy says he spent 10 days absorbed in the Kaldor archives: a slightly strange experience for him, given that he destroyed his own archive, and all of his carefully catalogued 7227 possessions, in his 2001 London performance called Break Down. “I don’t like archives,” he declares. “I said: ‘If I can destroy my archive, I can destroy anything.’ ”

Each of the Kaldor Public Art Projects is allocated a floor area of identical size in Landy’s exhibition, but one project is evidently more equal than others. Wrapped Coast, being the first and largest, is recalled in several places at the AGNSW. On the ground floor are a mural photograph of Wrapped Coast and Christo collages of the project, as well as other of his works from the Kaldor collection.

Artists Imants Tillers and Ian Milliss, among the volunteers who worked on Wrapped Coast in 1969, have made new works inspired by it. And in the gallery vestibule — which Christo and Jeanne-Claude wrapped in 1990 — is a wrapped bunch of plastic roses, displayed in memory of Jeanne-Claude.

Christo was hoping to be in Sydney for the 50th anniversary of Wrapped Coast but he is tied up — what other phrase can be used in the circumstances? — with his next project, L’Arc de Triomphe, Wrapped. The venture will cost up to €14m ($22.8m), which he will raise by producing and selling original drawings and collages related to the project.

It came about this way. An exhibition is being organised at the Pompidou Centre about Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s Paris projects, including Pont Neuf in 1985. Christo says he was invited to produce an artwork for the Pompidou forecourt but, with characteristic alacrity, he says he told the museum’s director: “I will not do anything except wrap the Arc de Triomphe.”

It happened that the Pompidou’s president and director have connections with French President Emmanuel Macron and, voila!, in September next year the Arc de Triomphe will be wrapped in silvery blue polypropylene fabric and 7km of red rope.

The project will, in a sense, return Christo to his first years in Paris when, as a political refugee, he conceived of an idea of wrapping the monument at the top of the Champs Elysees. But Christo is an artist forever looking forward, never looking back.

“Each of our projects is like a journey in our life — unforgettable, you cannot return back,” he says. “That is the most exciting part of all the projects.”

Making Art Public is at the Art Gallery of NSW, from Sunday to February 16.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout