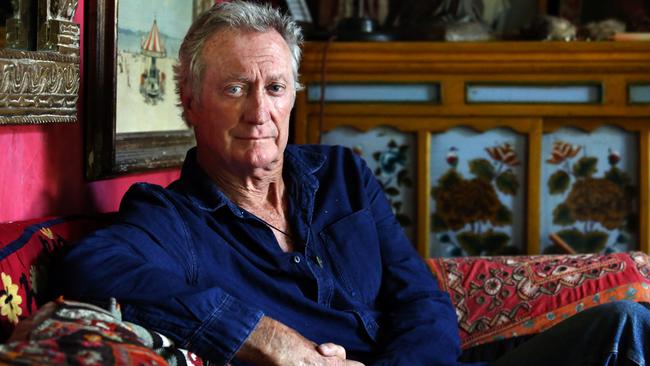

Bryan Brown receives Longford Lyell Award for lifetime achievement

Some actors lose themselves in their characters, ‘but I find myself in them’, says Bryan Brown.

Some actors lose themselves in their characters, “but I find myself in them”, says Bryan Brown. Yet the desire to be an actor took him by surprise. He was a young man from Sydney’s western suburbs, working in an insurance company, when he discovered what it was like to be performer and decided that was what he wanted from life.

Brown, 71, is the recipient of this year’s Longford Lyell Award, which will be presented next week at the Australian Academy of Cinema and TV Arts Awards ceremony. It’s a recognition of a lifetime of achievement, of a career as an actor and producer that spans decades and more than 90 screen credits. He’s happy to receive what he calls the “You’re Still Around Award”, and to marvel at how he managed to become an actor in the first place.

“There are certain sorts of character that I like to play,” he says. They may seem self-assured or archetypally masculine, but their assumptions are often challenged. “People are complex. The ones who struggle with who they are, I enjoy them.”

An example is Sergeant Fletcher, the police officer in Warwick Thornton’s Sweet Country, “a real man, a man who finds the world is a bit different to how he thought it was. Good stuff to play.”

He was happy with his job in insurance. “I didn’t mind going to work, I could earn money, buy a beer, pay my own way around, have a surf, life was good.” One day he was asked if he wanted to take part in a one-off revue. After the quick tryout, something changed.

“I was told, ‘Yeah, you can join, come to rehearsals tomorrow’, and I remember the strange thing was there was an excitement about going to work the next day that hadn’t happened in all the four years I’d been working.”

He then joined a local theatre group. A teacher recognised something in him. “I remember one day she said to me: ‘You want to be an actor, don’t you?’ I did, but I wasn’t game to say that to anyone. How did she know I had that deep desire?

“I think maybe you need shows. When it all comes down to it, and without being wanky, I think I had a need to act. I think I wasn’t going to be a satisfied person until I did this thing. Whether that was simply because I ‘needed to express myself’ and I’d stumbled across a way to do it. I certainly wasn’t going to do it through painting or writing, but I’d somehow stumbled across a way to say who I was, or something.”

A couple of years later, he took a bigger step. “I made this really strange decision to resign, sell my car, buy a ticket to England and start knocking on doors telling everyone I wanted to be an actor. Or that I was an actor.”

He left Australia because it never occurred to him that he could have a career here. “Whenever I looked around, all there was were American or English plays, I never saw anything with people I recognised on stage.

“I thought: ‘I’ll go to England, I’ll become an Englishman and I’ll act in English theatre.’ And 18 months later I had a year’s contract at the National Theatre.” Peter Hall had just taken over as director, and in that first year Brown had small roles in Frank Wedekind’s Spring Awakening, and in Romeo and Juliet and The Tempest. “When I did The Tempest with John Gielgud as Prospero, I mean, I was a fairy, a tree, a sailor, I was all sorts of bits and pieces, and that was so fantastic — as fantastic as him playing Prospero.”

There was something nagging at him, however. “I stood backstage watching John Gielgud a few times and I remember thinking one time: ‘You’re really good at what you do and I couldn’t do it. But I can play a bloke from Bankstown, and you can’t.’ ”

He came back to Australia for a few weeks’ holiday, and found that much had changed in his absence. “David Williamson was writing plays with Australian characters,” he says. “And Peter Weir was doing Picnic at Hanging Rock.” Here was now a place for “boys and girls from Bankstown”, in theatre and in cinema.

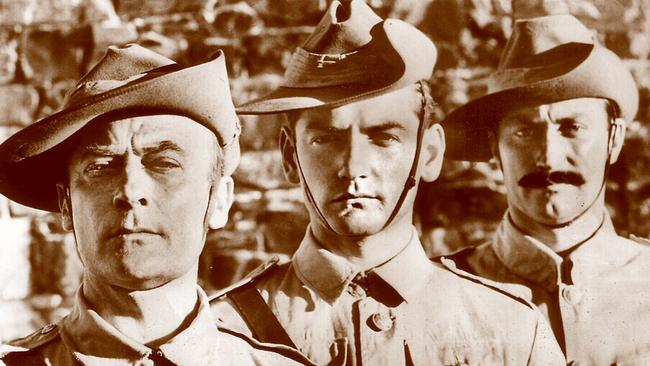

He hadn’t thought about movies before, but it quickly became apparent that it was the place to be: “Because in those days, how could you not want to be?” The roles came, in films such as The Love Letters From Teralba Road, The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith and Newsfront. His breakthrough role was in Breaker Morant, Bruce Beresford’s Oscar-nominated drama about three soldiers executed by firing squad for killing Boer prisoners of war. “I almost think we made too many good movies too early,” Brown says. “We should have held a couple back. My Brilliant Career, Breaker Morant, Mad Max, The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith … so many good things. We should have done it over 10 years instead of three.”

International attention meant film and television offers from overseas. For Brown, the two projects that got him the most attention were Breaker Morant and the TV series A Town Like Alice.

“Suddenly, there was the opportunity to do things on a bigger scale. The task is the same; when they say ‘action’, you better be real. But now I had the opportunity to have an adventure worldwide, to go to India, Hawaii, Jamaica, Rwanda — it was pretty cool.”

His first international production was The Thorn Birds, the 1983 miniseries based on Colleen McCullough’s novel, set in Australia but filmed in California and Hawaii. This was where he met his wife, English actress (and, later, director) Rachel Ward, also a cast member. He was nominated for a Golden Globe and an Emmy for his role as opportunistic shearer Luke O’Neill.

In Cocktail, as cynical barman Doug Coughlin, he inducted a young Tom Cruise into the tricks of the trade, and starred opposite Sigourney Weaver in Gorillas in the Mist: spending time among the mountain gorillas was an experience he treasures. Another was being at the Venice film festival last year, watching the rapturous reception for Sweet Country.

“The biggest thing I faced at one stage was whether I would do Australian movies any more,” he says, “and I thought: ‘That’s more important than anything else, I’ve got to work out how to do that.’ ”

There are things you learn to expect on a set after years of working in the industry, yet nothing is ever the same. “There’s a structure that goes into making movies, but the personalities of the people come through,” he says.

In a recent film, The Light Between Oceans, he recalls filmmaker Derek Cianfrance shooting hundreds of hours of film, and never using the words action or cut: scenes had no explicit beginning or ending. “He was very much about actors having their space, it was almost like rehearsal all the time, which was really lovely.”

No one else has been like Cianfrance, Brown says: as an example of a very different approach, he cites Beresford. “He once said to me: ‘I can see my movie in my head.’ His experience was great to be around. He’s wonderful on the set. His great strength is that he can communicate with each actor in the way they need it. With me he’d be flippant, with someone else he’d be serious, whatever it was to help you get what you needed that day.”

Whatever the movie, Brown says that as an actor it’s always about giving yourself over “to this piece we’re trying to create”.