The case to change the name of Mount Kosciuszko, Australia’s highest peak

The real-life Kosciuszko never even set foot in Australia, let alone climbed our highest peak. Is it finally time to call it by a name Indigenous people have used for tens of thousands of years?

Australia’s highest peak – Mount Kosciuszko – is named after a man who never stepped foot on this continent. Should we change it, maybe to something approved by the Ngarigo people, who still live nearby?

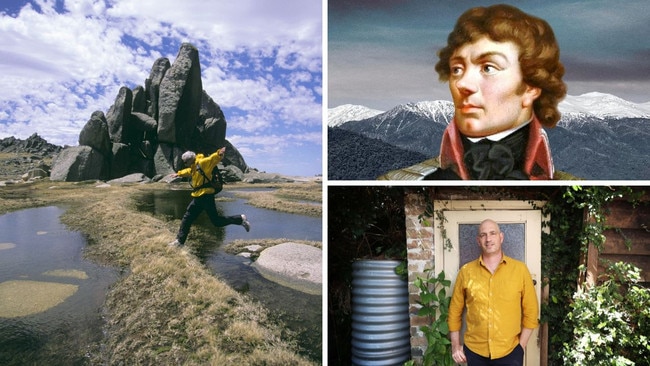

Writer Anthony Sharwood considers this question in his new book, Kosciuszko: The Incredible Life of the Man Behind the Mountain (Hachette), out this week.

“There’s certainly an appetite for change, but it’s not going to be easy to find a new name that everyone agrees on,” says Sharwood.

“Australians like the name Kozzie, even if Aboriginal people call the mountain by other names. The other problem is, many Aboriginal people were pushed off country, and there is no way many of them can afford to live (near the snowfields) anymore, and so there are disputes as to whose name to use.”

Sharwood, whose two previous books are also set in the Australian Alps, says he decided to write a book about Tadeusz Kosciuszko after waking one morning, thinking: “wait, who is this person?”

“I was so familiar with the mountain, and I didn’t really know anything about the person it is named after,” he says. “After I started researching him, I fell in love with him, because how could anyone not? This was a man who tried to free the enslaved of Thomas Jefferson. He’s unblemished, he’s uncancellable. He was saying ‘black lives matter’ two hundred years ago. You couldn’t find a better person.”

While there is debate about how the mountain came to be named for him, Sharwood says “the big lie” is the way Australia has ignored the fact that “for tens of thousands of years, the mountain had other names”.

“In speaking to Ngarigo people, it became very clear to me that while some of them admire (Kosciuszko) and have wonderfully sympathetic things to say about him, they do have their own stories about the mountain, and their own names for it.”

The Ngarigo nation is broken into several clans, or family groups, each of whom traditionally occupied different parts of the mountains or nearby foothills. They would meet in the region now known as “the Snowy Mountains” for the Bogong moth migration.

“They’d feast on them,” he says. “And these different groups, different mobs, have no single spokesman.”

For his book, he spoke to Aunty Rhonda Casey, an elder of the Monero-Ngarigo people, who called the mountain “Kunama Namadgi.”

He also spoke to elder Iris White, also of the Monero-Ngarigo mob, who told The Weekend Australian that she uses a different name, “but the elder who carried the traditional name has passed, and we are reluctant to share that information … I am part of her extended clan and we have to come together as a family, and as a people, and decide where we take it”.

“But you know, it’s been difficult for us as a people. We have lost our voice in that country. We will always claim sovereignty over that country, but we no longer live on country … you’ve got to remember, the history of our people is being pushed off that land, being removed from country.

“It’s the playground of the privileged up there these days, and we only get engaged when some agency needs to feel like they have ticked a box and engaged with us, government agencies, particularly, want to be seen to be engaging with us, but how meaningful that engagement is, I don’t know, and there are other groups claiming sovereignty as well, there is a lot of Aboriginal identity fraud, so behind this story is the bigger story, dispossession.”

The difficulty in finding a suitable name acceptable to the many Indigenous mobs is compounded by the fact that many Australians quite like the name as it is.

“When people say Mount Kozzie … I mean, I think the first sign of acceptance in Australian life is having an abbreviated nickname,” says Sharwood.

“It’s become part of our culture. It’s right there in The Man From Snowy River, it’s in a Midnight Oil song. We love the sound of it.

“And this guy – Kosciuszko – he fought for the dignity of indigenous people, the poor, the enslaved, the indentured, his whole life. As long as there are divisions, keeping Kosciuszko may well end up suiting everyone, as long as Australians understand that yes, he was never here, but you could not have a better human being to remind you of what in life is important.

“Were it to be altered or removed entirely, many would rage against the change. Rightly or wrongly, it’s become a quirky Australian name, far removed from the correct Polish pronunciation.”

Kosciuszko – the man – was born in 1746 in what is now Belarus, but he travelled widely, and he was a war hero in three countries. The Australian mountain is not the only place in the world named for him (for example, there is a misspelled Kosciusko in Mississippi, whose most famous daughter is Oprah Winfrey).

Kosciuszko’s name was bestowed upon Australia’s highest peak by a Polish explorer, Pawel Strzelecki, who climbed – and named – it for him in 1840.

If the name were to change, it wouldn’t be the first time: while Strzelecki correctly named the mountain “Kosciuszko”, it soon became “Kosciusko” on the Geographical Names Board of NSW, and for half a century it was spelled incorrectly. The missing “z” annoyed a Polish-born Australian called Marian Szuszkiewicz-Landis, who campaigned for the name to be corrected.

The group received support from no less than the Polish-born pope John Paul II. Miraculously, as it were, the “z” was reinstalled.

Sharwood says that’s “as close to divine intervention” as he’s ever seen.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout