Pleasure and pain

David Foster captures Australia better than most and that makes his books challenging to read.

There is a wise Englishman I know who sells beautiful rare books and spends his weekends glued to the national rugby league. After many years based in Australia, he wrote back to his London-based compatriots via a group email, boiling decades worth of close cultural observation to its broth. “Australian humour,” he observed, “is essentially cloacal.”

His words returned to mind in the opening pages of David Foster’s 16th novel, The Contemptuary, where one Dudley “Dud” Leahy, senior assistant super of Goulburn Correctional Facility, zeros in on the central feature of each and every prison cell: an exposed toilet.

So when you’re inside you live in a dunny, you eat in a dunny, you sleep in a dunny and you share your dunny, for the most part, with a stranger who also lives in the dunny. That’s to remind you that you’re a piece of shit and what’s more, a bigger piece of shit than most. When Pico della Mirandola coined the phrase “the dignity of man” in the fifteenth century, he must have forgotten that he had an arsehole and he hadn’t completed his gender studies course.

Those who know and admire Foster as the pre-eminent Australian satirist of his generation — the smartest and most profane of his peers, the bitterest too — will recognise the method: sentences built from comic repetition and earthy patois; name-dropping some recondite grandee of European intellectual history to drive the baseness of our current moment home; and that final surplus to requirements politically incorrect swipe.

For all his dinkum locutions and mock-scholarly schtick, Foster has never felt more like our resident Jonathan Swift than he does in these pages: a High Tory moralist with a potty mouth who sticks it to foolish lefties and faux conservatives with equal vigour, his weapons ferocious smarts, vivid prose and crotchety common sense.

The passage above marks the beginning of a meditation on the dehumanising nature and weird anthropology of our carceral system. As it suggests, Foster is willing to go anywhere to describe what Italian philosopher Antonio Gramsci, no stranger to the prison cell, called the “spiritual deformations” invariably suffered by long-term inmates. But it is a novel simultaneously concerned with the decline and fall of organised Christianity in Australia (with special note given to the near-total extinguishment of monastic life), which Foster sees as the melancholy concomitant to the rise in popularity, if that is the correct term, of jails. Both are places of retreat from the world, of course. Both are run along rigid lines, strictly policed and built on surveillance.

But one set of communities grew up along principles of self-selection and self-discipline; monasteries and nunneries were dedicated to the greater glory of an ultramundane being — that, or ground-level care for her creations. The others are places of violence and despair, where addiction and abuse run rampant and God is entirely elsewhere.

What complicates this strict demarcation is the discovery in recent years that a significant minority of those involved with the church acted in ways that were anathema to central tenets of the Christian faith. They used their power over the laity, especially the young and the vulnerable — as well as the respect and deference accorded to them by the broader community — to commit and cover up horrific crimes, the scale of which is only now coming to full light.

The Contemptuary is an effort to come to terms with the point where the two worlds cross over and it does so by using an oddly appropriate genre: the whodunit.

Dud Leahy (yes, you read right; he’s impotent) our now-retired narrator, looks back at his long and not particularly impressive career in the NSW prison system as he attempts to solve the mystery of a handsome priest, jailed for acts of extreme sexual violence against children, who was eventually found dead in his cell. Leahy was the junior staff member first to the scene, one that bore signs of suicide and ritual killing. He has never fully recovered from the trauma of it.

Our narrator leaves the small farm where he had holed up in recent years, an ageing divorcee riddled with cancer, and sets out to haunt the old ground in the hope of expunging that memory. And that mainly means Goulburn jail, with its grand hand-carved sandstone gates and convict-designed buildings of brick, stone, slate and iron, built along a radial plan with the prison chapel at its heart, an architectural monument to the interrelation of punishment with redemption.

Indeed, for much of the life of the prison it was a place for young offenders, a site where quiet agricultural labour was designed to set first-timers back on the right path. Only in more recent decades were the “Supermax” components of the prison added at considerable expense. This is the prison the old employee returns to: a neoliberal testament to the privatising urge of the modern state, with its sterile bureaucratic nomenclature and retributive pettiness.

Foster makes terrible sport of this shift in the prison’s nature. Through the perspective of Dud and his dwindling cohort of lay and religious workers once associated with the jail, we trace a shift in the temper, not just of a correctional institution but also the wider culture.

The facility and surrounding town and country have always been economically and socially connected. As the local homes of various religious orders empty out and the village kirks fall into disrepair, in preparation to be sold off for tree-changer’s housing, the special section of the correctional facility fills with convicted sex offenders.

Dud, who lives on the region that Foster has called his own for many years, and who speaks with his creator’s tones of humour and world-weary asperity, remains finely balanced when it comes to the situation at hand. It is hard to work out whether he is more horrified by the historical crimes committed by those in the church, or the shrill and vulgar “feels” of the social media mob who decry them.

Mainly, he drives between interviews with former screws of his acquaintance who he presses for information about Brigid Poidevin, a beautiful young Irish nun who, in her role as pastoral support to her coreligionists in Goulburn jail, would have heard the confessions of Simon Bourke — the ruined Passionist priest who apparently necked himself in A-wing all those years ago — before herself dying in a car accident soon afterwards.

This is not a crime novel in the usual vein, however. It’s closer to one of those metaphysical mysteries by Joseph Conrad or GK Chesterton in which the revelation of wrongdoing expands to enfold all victims and all perpetrators.

Dud Leahy’s own failures as a man bind him in tragic loyalty to both sides of the moral ledger. After years spent in proximity to human error and human evil, he evidences a kind of survivor’s guilt.

The primary engine of Foster’s fiction has always been that of performative voice rather than that of psychologically centred subject, but here the gap between disembodied stylistic talent and individual subject begins to narrow.

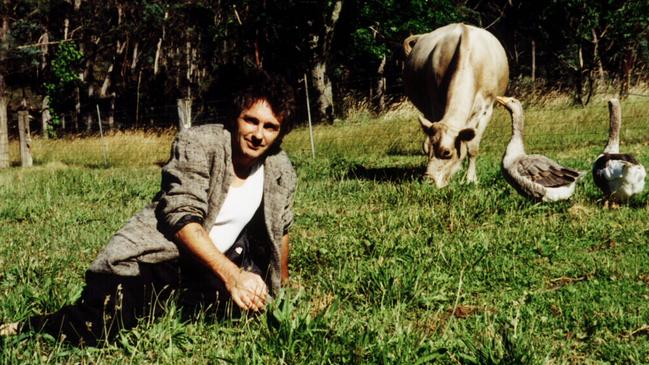

Foster, who won the 1997 Miles Franklin for The Glade Within the Grove, has written of Australia better than most. He has riffed on spirituality and spirit of place before with startling intellectual vigour. Yet in these pages he seems to admit some more personal connection with the material at hand. This feels like his patch of earth and this feels like his own residuum of idiosyncratic belief being shredded by the accumulated crimes of the local church.

There is, indeed, an almost Larkinesque plangency to the author’s descriptions of place: a sense of a world no longer infused with any saving sacral intensity or ordinary communal life. It is perhaps the demographic blind spot of every generation to feel that those who come after reflect some falling away; however, in Dud Leahy’s road trips through the empty hamlets of the southern highlands and central-western NSW — hot on the trail of an ancient crime that may or not have been committed — the reader is almost convinced that our sins will remain unforgiven for lack of any agent worthy to do the job.

There is no such thing as a Foster novel without the free and fertile play of an epic imagination. And typically, the author’s satire is laced with a rancour that often overwhelms its subject.

But there is a low moan running beneath all the intellectual buoyancy in The Contemptuary, a cold current of unillusioned despair and pain. It is, like all the author’s fiction, a pleasure to read for all the same reasons that others avoid his work. It is honest — jarringly, unsparingly honest — and no one emerges from its pages untouched by the general ordure.

Geordie Williamson is The Australian’s chief literary critic.

The Contemptuary

By David Foster. Puncher & Wattman, 174pp, $29.95