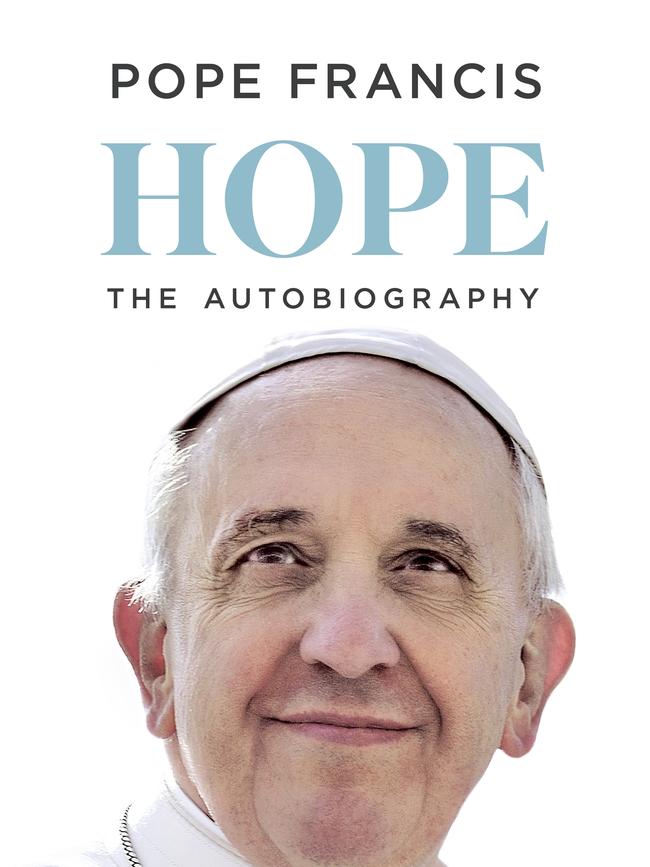

The Pope on faith, hope ... and girls

Pope Francis is the first Pope to publish a memoir during his lifetimes, writes former priest, Michael Costigan

Hope is the only autobiography released by a living Pope. Yet it is far from the incumbent’s only innovation. At the very outset of his pontificate, the former cardinal became the only Pontiff to choose the name Francis. He made his choice after being prompted by close friend, the late Brazilian cardinal Claudio Hummes OFM, who had reminded him to give priority in his mission to the poor, whose model and example had always been the 13th century’s St Francis of Assisi.

Pope Francis’s book has been published just ahead of the 12th anniversary of his election on 13th March 2013, as part of the Pope’s celebration of 2025 as the Jubilee Holy Year (the 2025th anniversary of the Incarnation of the Lord, which he has described as a time for Catholics to renew themselves as “Pilgrims of Hope”.) By chance, it comes just as Conclave, the Oscar-nominated film, is showing. Readers who have seen the film may be intrigued to know that Jorge Mario Bergoglio (the Pope’s name when he was still the Argentinian cardinal) received the required majority of votes in the Conclave’s fourth ballot. On formally accepting the result, he succeeded the retired Pope Benedict XVI – formerly the eminent German cardinal Joseph Ratzinger – who had surprised the Catholic world by his decision to step down.

It may also be worth noting that Bergoglio had been the runner-up to Ratzinger at the Conclave of April 2005. Many of the cardinals voting in the fourth round would have remembered how he had been a prominent candidate for election eight years before. He firmly denies that he came to the new Conclave with an expectation of success. A query from a Spanish-speaking cardinal about a reported missing lung was the first sign he was in the running again. He minimises the lung issue, recalling the successful removal of three cysts in the upper lobe in 1957, just before he entered the Jesuits Order.

Unprepared for election, he recalls his unintentional failure to abide by some of the usual procedures. He made world news with his friendly “Buon giorno” greeting from the central balcony of St Peter’s Basilica to the large crowd below.

Other early actions were also reported by the media, like his insistence on accommodation in the clergy’s Casa San Marco guesthouse next to the Basilica instead of in the much larger private papal suite; his preference for car transport in a humble small vehicle instead of a limousine; and his return to the lodgings in the Via della Scrofa where he had been staying, to pay the bill. It was a fellow guest and friend there, Archbishop Agostino Marchetto, who later remarked that Bergoglio “never laughed” but “now he does it all the time”.

Numerous similar examples of the positive, optimistic and often humorous approach of Pope Francis are in these pages. They are balanced, of course, by his serious, critical and even angry response to events within the Catholic Church and the wider world. One of the many faults, mistakes and personal “sins” that he acknowledges repeatedly in the hope of self-improvement is his tendency to impatience.

He acts with haste when grave episodes like the Russian attack on Ukraine occur. He went straight to the Russian ambassador, telephoned the Ukrainian President and did what he could, unfortunately without success, to try to bring about a compromise.

Early critics of Hope have observed that it really has two halves – the first about the Bergoglio family background, the second consisting mainly of Francis’s reflections on a host of issues. In everything, however, he advocates calm and charitable dialogue.

The future Pope was born on December 17, 1936 in his parents’ single-room apartment in Flores, Buenos Aires. His father, Mario Bergoglio, had migrated from Piedmont, Italy. His mother, Regina Mary Sivori, was a second generation migrant whose ancestors had also lived in parts of Northern Italy not far from Piedmont and Liguria. The chapters about the lives of the Pope’s parents, with two sets of grandparents living not far away from them, are full of interest. We learn that his mother wanted him to become a doctor. He lived with four younger siblings in a large house, without what we would regard these days as necessities. There is real charm in the way the Pope describes what he calls the “roots” of what lay ahead for him, the Church and the world.

He admits being attracted to a few girls, but he says it’s wrong to say that he was ever officially engaged. He confirms that it had never occurred to him to marry but he did find himself infatuated by a girl from a tango-dancing group, and another “beautiful girl” he met at his uncle’s wedding.

“For a while, yes, she turned my head,” he writes.

He struggled with his affection for her, but was able to “choose the religious path once again” and, after a bout of surgery, decided to join the Jesuits. Exceptionally positive are the chapters Francis has written on the formal education he received, from kindergarten to university, in philosophy and theology schools; and the education he imparted, as a high school teacher of the humanities, literature, art and psychology.

In another chapter, the Pope discusses his favourite sport, soccer, and the fortunes of San Lorenzo, his beloved Buenos Aires side. He believes that sport can be “a wonderful training ground in life”. However, a vow he made in 1990 not to watch TV has prevented him from watching San Lorenzo on the screen for 30 or more years. Deeply offended by a sordid scene that appeared unexpectedly in a program his community were watching, he made his anti-TV vow to Mary, the “Virgin del Carmen”. A Swiss guardsman leaves the soccer scores and statistics on his desk so he can stay in touch with the team. He also says “the most beautiful football matches are those played in a local square, on a cobbled street, on a garden lawn or on a sunbaked dirt road”.

“Let’s see who’s coming into the team with me,” writes Francis. The invitation from this talented papal wordsmith could apply to the whole of his instructive memoir, if one is willing to pardon trivial defects, presumably caused by the haste with which it has been published, which were, in turn, presumably so it could play its proper part in Francis’s Holy Year. The difficult virtue of forgiveness surely remains a favourite with him.

With his unqualified denunciation of every war in principle, making particular reference to those in Israel, Gaza and now so many other countries, the Argentinian Pope also speaks of our having “pillaged, polluted, exploited natural resources without restraint, to the point of threatening our own existence and that of our brothers and sisters”.

In his eyes, one of the great emergencies of our time is to honour “the divine mandate to protect our common home”. Political leaders of all persuasions should take note.

Michael Costigan is a writer. He was formerly a priest who lived and studied in Rome, and then a journalist. He was a founding director of the Australia Council’s Literature Board under its first chairman, Geoffrey Blainey.