Partnership forged in the jungles of wartime Borneo

Tales of heroism from World War II keep coming and in hindsight they seem more incredible than ever. Semut is one of those stories, untold until now.

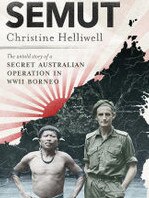

Semut: The Untold Story of a Secret Australian Operation in WWII Borneo

By Christine Helliwell

Michael Joseph, 562pp, $34.99 (PB)

-

Tales of heroism from World War II keep coming and in hindsight they seem more incredible than ever. What strikes me in this age of risk averseness is the courage of so many under duress. Semut is one of those stories, untold until now.

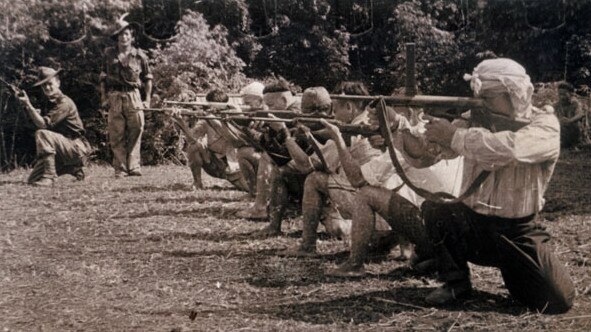

It involves an operation in late March 1945 when eight Allied operatives, in two groups of four, most of them young Australians, parachuted into the Japanese-occupied island of Borneo. In mid-April 1945 another eight operatives parachuted into Borneo, which the Japanese had invaded in December 1941.

Thus began the ultra-secret Operation Semut. Its aim was to recruit indigenous, mainly Dayak, people to help defeat the Japanese.

Some Dayaks previously had never encountered Europeans, while most Allied soldiers previously had never met indigenous people. The soldiers didn’t have any local language skills and knew little about the Dayaks other than that they had been, and possibly still were, headhunters.

Semut is a riveting history of the covert Australian military operation of that name launched deep behind Japanese lines in Sarawak. It was conducted by a shadowy organisation codenamed Services Reconnaissance Department, often known to the troops as Z Special Unit.

Christine Helliwell is a distinguished anthropologist with nearly 40 years first-hand knowledge of Borneo and its indigenous people. As she explains, Semut is the Malay word for ant.

To piece together this remarkable story, Helliwell not only read a cache of military documents, archival material and newspapers, including the Sarawak Gazette, but she also interviewed Dayaks with intimate knowledge of the Pacific war, including one or two who confirmed that in 1945 Semut operatives had encouraged them to headhunt the Japanese.

Helliwell has interrogated almost all surviving Semut operatives and some of their families. In particular, she has drawn on the memories of her friend, Jack Tredrea. In civilian life he was a tailor from Adelaide. At 24 he led a troop of local Dayak tribesmen in a jungle war against the Japanese. Promoted from sergeant to warrant officer class 2 in July 1945, he was also the party’s medical orderly

It was Tredrea who told Helliwell that, in naming the operation Semut, they were likening the operatives to ants: tiny and largely unseen but also able to sting.

Focusing on Allied activities in the jungles of Borneo and along its great river systems, including the Baram, the Rejang, the Tutoh and the Tinjar rivers, this fine military history provides a detailed account of a brutal guerrilla campaign that succeeded only with assistance from the Dayaks.

Helliwell evokes the realities of life in the cavernous, noisy Dayak longhouses and especially of the lush and fetid jungles in which the Allies were embedded. At times the men of Operation Semut were unsure whether the jungle or the Japanese posed the greater threat.

Helliwell’s meticulous research results in a fascinating account of the highly effective combination of two extremely different cultures in what ultimately proved to be the common cause of defeating the Japanese.

Of the 120 Allied operatives who participated in the overall operation not one was killed. It is not surprising that, for the rest of their lives, Semut operatives exhibited an enduring grateful admiration of the Dayaks. As Tredrea put it, “None of us would have survived more than a day or two without them.” And as signaller Bob Long said in 2014, “The Dayaks were our saviours, really.”

Helliwell writes: “The Dayaks took the operatives in, cared for them, fed them, and taught them how to survive a seemingly deathly environment. They also ate, slept, fought and died beside them. And finally, they ensured that every one of them returned home.”

Semut is superbly illustrated, well indexed and lucidly written. As well as canvassing the pivotal role of a rich variety of Dayak groups in Allied military operations against the Japanese, this brilliant book also highlights the wanton destruction of Borneo’s jungles that has occurred since the end of World War II.

This, Helliwell says, has been caused “by rampant logging and the establishment of vast palm oil plantations”. She has been trekking through the jungles of Borneo since the mid-1980s, and preserving what remains of them is a cause close to her heart.

Ross Fitzgerald is emeritus professor of history and politics at Griffith University and the author of 42 books, most recently the memoir Fifty Years Sober (Hybrid).

Semut: The Untold Story of a Secret Australian Operation in WWII Borneo

By Christine Helliwell

Michael Joseph, 562pp, $34.99 (PB)

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout