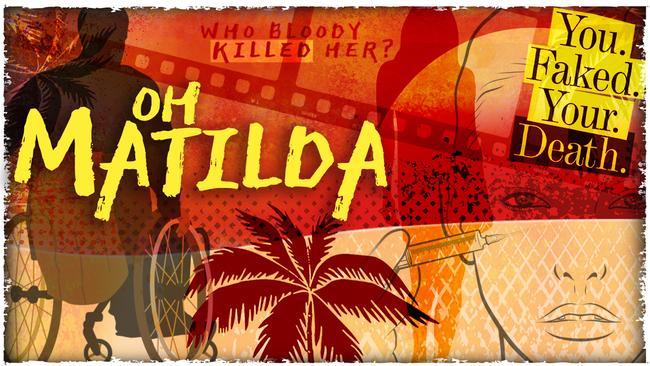

Oh Matilda: Who Bloody Killed Her? Chapter 16

Things are changing, and not in a way John McCredden likes. Author Carly Findlay takes up the story

This is ‘summer reading’ like nothing you’ve read before: a diverse field of writers collaborating on a novel that will captivate you through summer.

Each author had just three days to write their chapter, with complete freedom over story and style; it’s fast, fun and very funny.

Tune in over the summer to see how the story unfolds and click here to start from the beginning.

Today, Carly Findlay continues the story.

McCredden blinked.

Matilda Meadows wasn’t dead. She was standing in front of him, wearing cut off jeans and a black T-shirt with “Always Was Always Will Be” in yellow and red letters. Dark regrowth coming through her vodka-bleached hair. She was holding a ring-clip binder, filled with sheets of paper.

She had no obvious signs of injury, and certainly no obvious signs of death.

“Bloody hell. We’ve been investigating your death, Matilda. What’s going on?” McCredden asked, still stunned.

“McCredden, I’ve been working on a project. Needed some time to think.”

McCredden smacked his palm to his face, wiping beads of sweat. He had cuts on his body from the sharp leaves. He took a tentative step closer, nervously expecting Matilda to have company.

She sensed his apprehension. “It’s OK, I’m just here with a few mates. They’re harmless. But we want to talk.”

Matilda gestured McCredden to come inside.

He cast his eyes beyond Matilda. The squat building wasn’t as derelict as it looked from the outside. It was modern. He noticed nine people sitting around the table.

The people waved, greeting McCredden.

“Who are these people?” McCredden asked, feeling a bit intimidated.

“Oh, they’re The Australian Screen Industry Diversity Working Group.”

“Sorry? Where did they come from?” McCredden asked.

“They’ve always been here, mate. You’ve just overlooked them.”

The Working Group members waved, inviting him to a spare seat at the table. McCredden sat down and Matilda walked to the head of the table. She remained standing.

The group was a diverse looking bunch, McCredden thought. Black and brown people, people with foreign accents, someone in a wheelchair, a plus-sized woman in a hijab, someone with a large facial scar … he’d never felt so outnumbered.

Matilda cleared her throat.

“While you’ve been trying to solve the mystery of my death, I’ve been working with the top diverse actors in the country. We’ve put together a blueprint,” Matilda said, with all the confidence of a CEO.

She continued.

“I organised with the morgue to get a stunt double of my body. Made it look like my dead body. The morgue has rubber cadavers. It was a real likeness of me.”

“Faking your death?” McCredden spluttered, sweating even more now than he did walking through the jungle. “That’s a bit extreme.”

“What is extreme is the lack of diversity on Australian screens.”

McCredden looked at the Black man in the wheelchair. He was holding the remote control to the air conditioner. “Mate, can you turn up the cooling a bit, I’m boiling up?” he asked. He wondered if it was OK to call him mate – he’d never spoken to a person in a wheelchair before. They’d never been able to get on set.

He obliged, turning up the cooling, and introducing himself. “I’m Matthew Porter,” extending his hand.

Matilda interrupted.

“As I was saying, we need an urgent diversity overhaul. And so I created a decoy so we could focus on this. Oh and this concrete block, it was the most accessible place any Australian TV set has to offer,” she said.

“We’ve spent a solid amount of time here. It’s been productive.”

“You. Faked. Your. Death,” McCredden said, through his teeth.

“I’m just a girl, standing in front of a white male Logie-winning actor, asking him to think outside of his narrow lived experience for a minute.”

That line was familiar, McCredden thought.

“Who do you have to screw around here to get a diversity quota for film?” Matilda said cheekily, winking.

A small Indian-Australian woman with a facial scar ran her finger down Matilda’s back, curving around to her stomach.

“We’ve been working so hard, haven’t we?” Matilda said sweetly, picking up Nita’s hand to kiss it.

McCredden was puzzled. Why was Matilda quoting lines from Richard Curtis movies to him?

And why do things need to change? Home And Away has been going along just fine with an almost all-white cast since it began.

Matilda regained her composure. Be professional, she thought. This might be the only chance you have to influence the industry.

“Those Richard Curtis films haven’t aged well,” she said. “But do you understand the reason I had to fake my own death? Because no one was paying attention.”

Matilda handed McCredden the binder.

“This is what we’ve been working on,” she said. He opened it, as the others looked on, smirking to themselves. They knew this document had the power to create solid industry change.

The document’s cover page read: “Diversity plan for the Australian screen industry.”

McCredden cleared his throat. He admired Matilda’s bold decoy plot, he’d give her that. But he couldn’t wrap his head around this.

“Is there really a need for this, Matilda?” McCredden asked, irritated.

“Surely we could have just had a chat at the bar after filming one night, rather than interrupting the entire filming schedule and involving everyone on set to solve your murder.”

She drew breath.

“I’ve been typecast as an Aboriginal actor too many times, and so have my mob,” she began.

“Non-disabled actors get accolades for playing disabled characters. Culturally and linguistically diverse actors only ever get minor roles. Women are still expected to remain looking younger than their actual age, while men never have to get Botox. Hedwig and the Angry Inch was going to be played by a cisgendered man. And have you ever seen a newsreader with a facial scar?”

McCredden’s head was pounding – he had heard of some of these buzzwords, but switched off when the woke Millennials talked about Black Lives Matter and transgender rights.

I should have paid more attention, he thought. It was hard to learn this tolerant terminology at his age, especially when he’d had so many starring roles.

Matilda walked behind him, flipping the page to the executive summary.

There was a list of outcomes:

-There must be diversity quotas for screen actors and crew. The dominant white actor must not be the default.

-Each screen project will be overseen by a diversity and access team.

-Accessibility must be considered from the outset – everybody should be able to get on set.

-Actors from diverse backgrounds need not only address the discrimination they face – they are entitled to well developed, multidimensional characters.

-Blackface and disability mimicry will be outlawed – actors who do this will need to donate $1000 of their wage to the relevant diverse community they’ve hurt.

-Comedians aren’t allowed to punch down in their jokes – again, there’s a $1000 fine.

-People with different body shapes and sizes will receive priority in casting for reality love programs.

-Marginalised people’s trauma is not privileged people’s entertainment.

-A bonus will be paid each time a person from a diverse background has to perform emotional labour educating the privileged (budget for at least $100,000 per film)

He looked up. “I’ve been blind to this,” McCredden apologised.

“That’s an ableist slur,” Amani Yusef, the woman in the hijab, corrected him.

“I’m going to touch base with Bradley Champion,” McCredden changed the subject, reaching in his pocket. “I’ll let him know you’re alive.

Before he dialled Bradley’s number, McCredden thought back to Maya Churchill, walking past Matilda’s dead body. Not Matilda’s body. A rubber version of her.

“Maya Churchill. Was she in on this too?” he asked Matilda.

“She stepped over fake dead me. But she’s not that cold. She’s been overseeing this project, she connected me with the morgue. As an older screen goddess, she wants to see better inclusion of older people on screen. She wants to be the next Bachelorette.”

McCredden sighed. Those lyrics were so pertinent now.

I feel a bit fragile

I feel a bit low

Like I learned the right lines

But I’m on the wrong show

McCredden felt more bruised than when he’d arrived. He really hadn’t ever felt this outnumbered.

To join the fun, click here for Chapter 1 or go to ohmatilda.com.au

Carly Findlay is a writer, speaker and appearance activist who has written a memoir, Say Hello, and is editor of a forthcoming collection, Growing Up Disabled In Australia. It will be released on February 2.