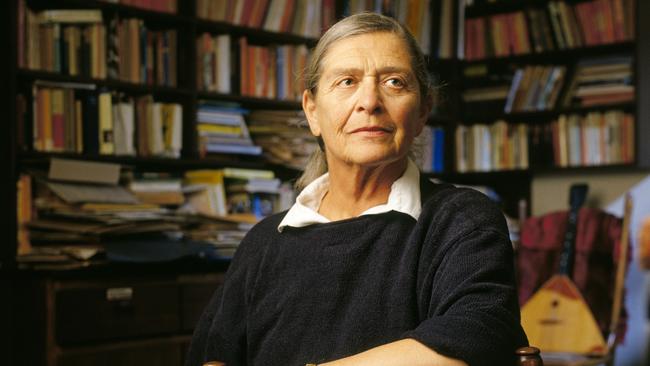

Obituary: Fay Zwicky, leading West Australian poet

WA poet Fay Zwicky has died, aged 83.

Fay Zwicky embodied several spheres of artistic endeavour, each of which she held to implacably, striking notes off a template that was soundly her own: a kind of unified musical field made of her being as a pianist, poet, critic and teacher. To each she devoted hardworking years that were leavened, you might say, by her life as a wife and a mother.

This ensemble of vocations rendered her a major poet, and a powerful intellect in Australian letters, unique among women of her generation. In a grand, edgy way, she thrived among the achieving men she mostly found wanting.

She affirmed an aristocratic cognisance of tradition as well as a democratically receptive attitude towards creations that were open-hearted and strongly new. She had a reputation as a stern, uncompromising figure, but she could be as generous and as compassionate as she yearned for the world to be. Even her savage ironies played off the melodies of love. She was as beautiful as she was intelligent and could be remorseful at any abuse of her own power.

Her intellectual preoccupations were laid out in 1985 in The Lyre in the Pawnshop. The essays were impressively, conspicuously cosmopolitan, a gust of fresh air at the time. The reader became aware that she was an Australian Jew whose defining interests in American and European writing were inseparable from the events of World War II. She read literature as a moralist. Her interests in American preoccupations with identity, authenticity and sincerity she treated incisively and personally, according to her own commitment to the truth-stakes of literature.

Over-archingly, whether she was considering George Eliot, Sylvia Plath, Thomas Hardy or Paul Celan she encompassed the relationship (or lack of) between “Love and Language”. In her essay of that title she has an epigraph by Karl Kraus: “Speech is the mother, not the handmaid, of thought.”

Her essays cast her as a matriarchal custodian of language. This was especially true when she ran her eye over the work of Australian writers who were embedded in their own stray speech habits on their vast continent. Rather like de Tocqueville in America, Zwicky set them against a neo-colonial canvas of what was at stake in a fledgling democracy.

In The Lyre in the Pawnshop, no one gets off lightly, except perhaps Rosemary Dobson, whose work is praised for its “reclusive grace”. Yet against this praise for a spiritual quietism, Zwicky regular affirms the gusto and the embrace of Walt Whitman, and the delicate perspicacity of DH Lawrence. Both writers were “vulnerable to experience”: they were alive to “living contact” with others, the very thing that should inform a teacher, Zwicky argued, which comes down to the joy and wonder involved in taking others as seriously as one might take oneself.

Zwicky expressed a sense of her life as a bid for freedom, a self-shaping out of the conventional cultivations of her Melbourne, middle-class family. From girlhood, her mother, a musician, had seen to her daughter’s musical performances. Zwicky was a professional musician until she was 32, playing with her two sisters as the Rosefield Piano Trio, and then as an international soloist. She excelled, but the demands of the concert halls were “agony”. So she turned back to the seedbeds of her progressive education at Merton Hall and her studies at the University of Melbourne, where she’d published her first poems as an undergraduate even before becoming a tutor in English.

“I’d always been a literary child,” she told the committee that judged her the winner of the Patrick White Award in 2005. “Even when I was supposed to be practising, I had a novel or a book of poems encaged behind the music.”

The “encaged” may have also referred to her urge to escape from the conservatism of Australia’s politics. Even as a 12-year-old at school, the news of the atomic bombs dropped on Japan in 1945 had a profound impression on her. She absorbed the leftism of the postwar period: for several decades she was prepared to see herself as “fellow traveller”, albeit “a sceptical one”.

She loved Australia with its democratic ethos, but she wanted it to be as awake to the life of the mind as the best of the older cultures. In a spirit of optimism, in 1972 she took up her appointment as a senior lecturer at the University of Western Australia (she had been living in Perth since 1960, when her first husband, a zoologist she had met in West Java, had taken up a teaching appointment).

Her first of seven books of poems was Isaac Babel’s Fiddle (1975), an exciting title for a woman to put out: Babel, a soldier in the Red Army, was the most vivid, direct of writers, unforgettably clear-eyed and the most complicated of partisans. The book was “spring-loaded”, as one critic said.

The same could be said of her next collection, Kaddish (1982). The title poem expressed her stormy resistance to family forces after the death of her father, a medical doctor and war veteran who died at sea in 1967. In its tidal articulations she took a leaf out of Kaddish by Allen Ginsberg, “old courage-teacher”. The poem works like a musical composition, shuttling inward and outwards, opening to the universe and its archetypes.

Ask Me (1990) is funny, defiant and down-to-earth about most things, including death. The Gatekeeper’s Wife (1997) is similarly witty, wide-ranging, argumentative, and unforgettably poignant with regard to the classical place of a woman striving to love a man whose strength/weakness is destined to be different to her own. “The gateposts of the house tremble”: the poem aches with the woman’s yearning and faltering with what was in the absent man’s character.

Picnic (2006) was a quieter collection, yet the most political of her books, and often set in China (responding to the terracotta army at Xi’an, and the slaughter on Tiananmen Square). The language is plumb-weighted with meaning, and as plain as WB Yeats his late years.

Zwicky got around. In America, to which her poet’s ear was constantly tuned, she taught in New York and in Illinois. But her vocation to teach young people in Australia kept bringing her back to Perth. Mature younger poets sought her out, sat at her feet. She was flattered, they were instructed and honoured in her poems.

She did good deeds for writing: editing collections (Journeys) and helping with literary journals (Westerly). She had a lot to give and she gave it readily. Incessantly she applied herself, worrying on behalf of us all.

Right until the end she had poems in the good anthologies. The 2016 Contemporary Australian Poetry closes with two of her best poems. One is called Losing Track, the last line of which expresses her state of mind towards the end: “You might say getting close to God without God”. The other poem is an elegy to the dead in war. It is called The Young Men and it ends: “Young men, you dear young men, I’m listening.”

Zwicky was a great listener and the sustained, complex quality of her work will long be calling us to listen back, as well we might when her journals, which she left with the National Library, see the light of day.

She kept them up for almost half a century. “Secular humanism and does it work? Does it matter?” she asked her journal recently. “We speak of the death of God and the loss of faith. Why don’t we speak of the birth of reason and the liberation of truth?” The journals were designed to be the best of her candid self, a woman who chronically felt in herself to be, in her last decades, short of peers as our “culture and character” went into its nosedives.

Among her accolades was her 2004 award as a West Australian State Living Treasure — an honour, no doubt, but it should not be idealised.

The Caller (one of her toughest poems) was to the bronze statue of the German expressionist sculptor Gerhard Marcks, which stands on the forecourt of the Art Gallery of WA. “Bronze brother …” it begins, “instruct me in your wordless patience, stilled ferocity … in this land of garish failure.”

Zwicky judged herself harshly for such lacerating tendencies, but to her credit she could hardly, artistically, help herself.