Booker Prize draw a novel way to cause an upset

The Booker Prize judges were told to decide between the novels of Margaret Atwood and Bernardine Evaristo, but they stood firm.

As usual, Margaret Atwood is right: rebellion is in the air. The Canadian writer shared the £50,000 ($93,000) Booker Prize with Anglo-Nigerian author Bernardine Evaristo on Tuesday after the judges defied the prize organisers and broke a longstanding rule prohibiting joint winners.

The surprise decision, announced at a black-tie dinner at London’s Guildhall after last-minute deliberations by the five judges, also set precedents.

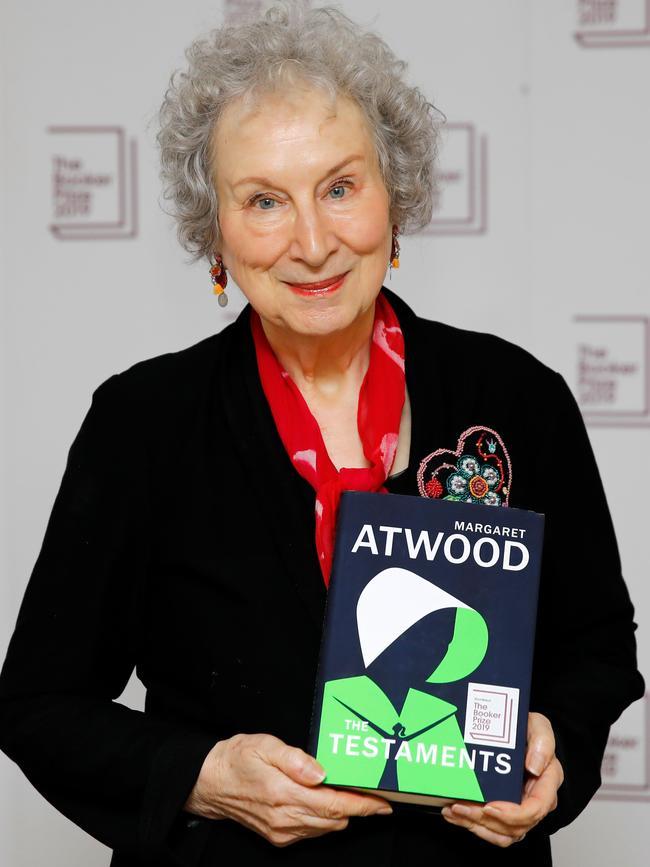

Atwood, who won for The Testaments, a sequel to The Handmaid’s Tale, became the fourth dual winner and, at 79, the oldest recipient of the award.

She said she was pleased to share the prize as “being a Canadian, we won’t do famous, it’s not a good look”.

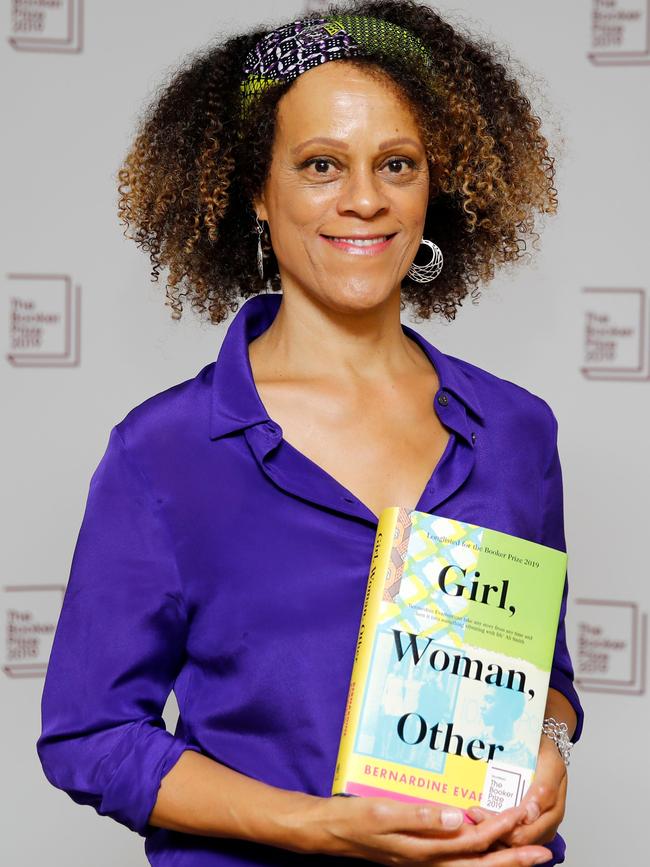

Evaristo, 60, who won for Girl, Woman, Other, a novel centred on marginalised women, became the first black woman to win the Booker, which was first awarded in 1969. She said she hoped “that honour doesn’t last too long”.

As the two writers took the stage, Atwood lifted Evaristo’s arm in a victory salute. She noted, with her characteristic humour: “We both have curly hair.” Evaristo said it was “incredible to share this with Margaret Atwood, who is such a legend”.

In The Testaments, set 15 years after The Handmaid’s Tale, cracks are starting to emerge in the totalitarian state known as Gilead. Rebels, within and without the ruling patriarchy, are gaining ground.

Girl, Women, Other considers the lives of 12 women, most of them black, across three generations. Evaristo was born in London to an English mother and Nigerian father. Both books offer glimpses of hope in dark times.

Head judge Peter Florence said Evaristo made “the invisible visible”, and Atwood’s dystopian Gilead “might have looked like science fiction back in the day … Now it looks more politically urgent than ever before.”

He said when he advised the Booker Prize Foundation chairwoman, baroness Helena Kennedy, that the two novels could not be split, he was told to go back to the other judges and sort out a winner. But the judges stood firm, despite “being poked with something like a cattle prod”.

Florence said: “We tried voting, it didn’t work, a metaphor for our times.

“This 10-month process has been a wild adventure. In the room today we talked for five hours about books we love. Two novels we cannot compromise on, so we decided the only course of action was to flout the rules. They are both phenomenal books that will delight readers and will resonate for ages to come.”

Florence noted that Guildhall was circled by Extinction Rebellion protesters. “We found the rules inadequate to the problem of how to privilege one book over the other. There is rebellion in the air and we were a little moved by that. If it is a rebellious decision, it’s also a joyful one.”

There have been two previous split decisions: in 1974 (Nadine Gordimer and Stanley Middleton) and 1992 (Michael Ondaatje and Barry Unsworth), at which time the Booker Prize Foundation instituted the one-winner-only rule. The foundation accepted the judges’ refusal to follow that rule. Its literary director, Gaby Wood, suggested the judges might not be paid. However, she added that their decision was “generous” rather than ‘‘aggressive”.

The other shortlisted novels were Quichotte by previous winner Salman Rushdie; An Orchestra of Minorities by previously shortlisted Nigerian writer Chigozie Obioma; the 1000-page epic Ducks, Newburyport by American-born, Scotland-based Lucy Ellmann; and 10 Minutes 38 Seconds in This Strange World by Turkish-British author Elif Shafak.

Atwood’s success sees her join JM Coetzee, Peter Carey and Hilary Mantel as a dual Booker winner. Her previous win was for The Blind Assassin in 2000. She has been shortlisted six times, including for The Handmaid’s Tale in 1986.

Some commentators see the split decision as a weak-willed compromise between awarding the prize to a popular bestseller (Atwood) and a more obscure but important writer (Evaristo). Without being in the judges room, it’s hard to know if that’s true.

However, it does seem that the sort of vote that denied Carey a unique third Booker in 2010 — 3-2 in favour of Howard Jacobson’s The Finkler Question over Carey’s Parrot and Olivier in America — was not possible. Florence said there was an “absolute consensus” that the prize be shared.

One imagines the controversy would be greater if the judges, unable to pick one winner, had decided to break the other post-1992 rule and withheld the prize.

The Booker is not the only literary award causing rebellion. The Nobel prizes in literature for 2018 and 2019, jointly announced after the award was held over last year because of a sex scandal in the Swedish Academy, prompted acclaim and alarm.

While the 2018 recipient, Polish writer Olga Tokarczuk, was well-received, bestowing the 2019 prize on Austrian writer Peter Handke was condemned by PEN America and individual writers such as Rushdie. Their complaint focused on Handke’s purported support of former Serbian president Slobodan Milosevic and former Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadzic.

“We are dumbfounded by the selection of a writer who has used his public voice to undercut historical truth and offer public succour to perpetrators of genocide,” novelist and PEN America president Jennifer Egan said. “We reject the decision that a writer who has persistently called into question thoroughly documented war crimes deserves to be celebrated for his ‘linguistic ingenuity’. At a moment of rising nationalism, autocratic leadership and widespread disinformation, the literary community deserves better than this.”