Artists aid mine town to dig deep

A COMPANY is backing art's ability to change the fortunes of Riotinto, as they did for Broken Hill.

BROKEN Hill photographer Robin Sellick describes the landscape with an artist's eye and the breathless ebullience of a romantic.

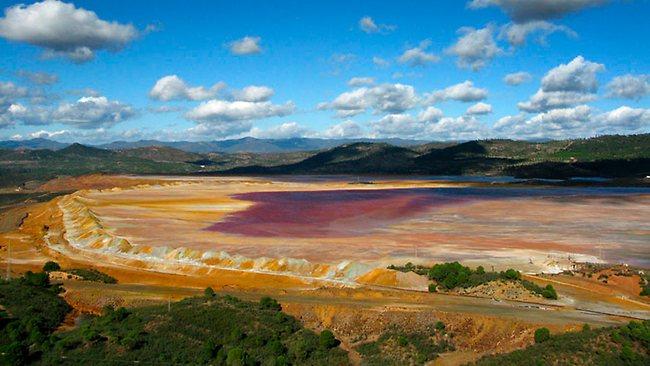

"It's like a master landscape," he says. "Enormous man-made sculptures loom over a river that runs the colour of red wine. Add to that the pinks, the greens, the blues. And the mine, well, the mine is beautiful . . ."

But the 44-year-old former Vogue photographer is not talking about his home town in NSW's northwest, famous for its once-thriving mining industry and as the home of BHP. He's describing the little-known Spanish hamlet of Riotinto, population 4500 and home to the largest mine -- albeit an inoperational one -- in Europe.

Sellick has just returned from a month-long visit to the Andalusian town, about an hour northwest of Seville, in his capacity as co-ordinator for the EMED Mining Cultural Alliance, an artists' program, backed by an Australian mining company, that links the towns from which the world's two biggest miners take their names.

"BHP started here (in Broken Hill), and now the company has nothing to do with the place," he says. "The same thing happened in Riotinto: the company took its name from the mine and now it has nothing to do with the town . . . We're unofficial sister cities."

The brainchild of Harry Anagnostaras-Adams, the Australian chief executive of EMED Mining, the cultural alliance program is unique, Sellick says.

The program, which celebrated its first anniversary in October, involves residencies and collaborative artistic programs between Australia and Spain (the program also now extends to the silver town of Banska Stiavnica in Slovakia). While the program is still in its infancy, Anagnostaras-Adams hopes to expand it to include exhibitions and residencies on a far grander scale.

Riotinto's mayor Rosa Maria Caballero Munoz was in Broken Hill recently for the program's latest incarnation, the unveiling of a series of rare Francisco Goya etchings at the Broken Hill Regional Art Gallery, which were on show throughout last month.

The works -- including an early edition of Los Caprichos, a set of 80 etchings by the Spanish artist from 1799 -- were hung alongside paintings by Broken Hill landscape artist Eric McCormick, who spent two months in Riotinto last year as part of the alliance program. "There are a lot of strange similarities between the towns of Broken Hill and Riotinto," Sellick says. "The mayor of Riotinto, Maria, herself was saying that when she was here. Walk into the bush in Riotinto, and you'd swear you were in Broken Hill, and vice versa."

Anagnostaras-Adams says the program represents an investment by the company of about $13,000 a month, which covers airfares, accommodation and materials for visiting artists, as well as visits by dignitaries.

He adds the partnership is about facilitating cultural and social renewal in the towns.

"We recognised similar heritage, opportunities and weaknesses in the mining communities," he says. "We put the artists up at company lodgings and meld them into the community interchange activities. They give their time and leave artwork behind -- that is the immediate contribution in physical terms. But the real penetration is social."

Riotinto is one of seven villages that comprise the Cuenca Minera de Riotinto, a "mining bowl" of 20,000 people -- incidentally the same population as Broken Hill -- that surrounds the copper mines, which purportedly have been in use for thousands of years.

The towns share a burgeoning, vibrant arts industry: a natural by-product, Sellick says, of their working-class sensibilities.

"There really is a strong arts community in Riotinto," Sellick says. "In the Cuenca Minera, there are probably 20 to 30 working artists. In Broken Hill there are close to 100, and 20 or 30 of those are taken seriously. So those synchronicities are how this program came about."

The only main difference, then ("other than the language") is money. The tiny town of Riotinto, just off the popular Iberian peninsula tourist route, is struggling.

Since the open-cut copper mine -- which measures 1.2km across and is 360m deep -- closed a decade ago because of a drop in metal prices, unemployment in the region has skyrocketed to 50 per cent. Sellick says the cultural alliance program is a way of helping the town carve itself a new niche, just as Broken Hill has done during the past 20 years.

"Riotinto is where Broken Hill was two decades ago," Sellick says. "The mine is very close to being operational again, but in the meantime this is a chance to rebrand itself, to move into tourism and art, just as Broken Hill has."

The red-dirt NSW town that spawned outback artist Pro Hart -- whose son, John, is part of the cultural alliance program -- once boasted 72 hotels. Now there are just 18. "Broken Hill now has more art galleries than pubs," Sellick says. "There are 100 working artists and 30 art galleries in the town. The arts are now such an important part of the culture and everyone understands that. It saved the town."

The next phase of the program takes place in February, with Broken Hill artist Peter McGlinchey travelling to Riotinto to work with local artist Pepe Pepereo on a project.

The artists will source discarded materials from the Riotinto region to erect a giant welcome sign, like Hollywood's calling card, that will read "Cuenca Minera de Riotinto".

McGlinchey will stay on site for two months working on the project, which will take various artists 12 months to complete.

"Peter and Pepe will work on a few letters, then more artists will come in later until the name is done. It will be a year-long process," Sellick says. "It will be a permanent artwork that will attract tourism (and will be something) for the residents to take pride in, to restore their faith in their home."

Sellick knows all about homecomings. He is a Broken Hill boy, born and bred. He left for the big smoke as a 20-year-old to forge a career in photography, admitting he was "happy to see the back of the place".

He moved to Sydney, then Melbourne, where he shot for Vogue and Rolling Stone, among others, before moving to New York to shoot alongside Annie Leibovitz and Mark Seliger. After establishing himself as an award-winning portrait photographer in this country, Sellick found himself gravitating towards the red, red dirt of home.

"This was the last place on earth I expected to come back to," he says. "I'd been away for about 20 years, and I just needed a break from work. I'd been living in Melbourne. So, about three years ago, I went back to Broken Hill to see my father. I said, 'I'll stay another week.' After that I stayed another week, then I just stayed."

The town has changed dramatically in the two decades he had been away.

"Twenty years ago, Broken Hill was still a rough mining town, and the reason it is what it is today is because of the arts," he says.

It has also become a popular film location. Mad Max 2 was filmed there, and the fourth instalment of the franchise had been slated to be filmed in the town this year. Reportedly, however, recent rains, which turned the desert into a "flower garden", mean the film will now be shot in Namibia. But Broken Hill is not a town for the broken-hearted. Sellick calls it a town full of eccentrics. (He chronicled them in Life and Times in the Republic of Broken Hill, a book of portraits of Broken Hill locals featuring an essay by Jack Marx, released last month.)

"There are some very, very unusual people here. But in Broken Hill that's seen as normal. Everyone accepts it. It's very inclusive. Very unique. I love it," he says.

It's a quirkiness of character Sellick says is yet to reveal itself in the town's Spanish sister city. "There is still a lot of depression there," he says. "People, really, are not their full selves. It's quite sad."

But he's nothing if not sanguine about art's ability to change the fortunes of Riotinto. "That's what this program is all about: rebranding the town, recapturing the light in people. Finding the colour in the landscape and restoring the town to its former glory."