Archibald Prize finalists are revealed at Art Gallery of NSW

The handful of competent paintings in the Archibald Prize are merely foils to the spectacle of excess, exaggeration and identity fetishism.

April, as TS Eliot wrote, is the cruellest month. He was of course referring to the rebirth of lust and longing in the spring after the long cold of winter.

For the critic, the cruelty of April lies in the obligatory carnival of the Archibald Prize, in which all the usual standards we take for granted during the rest of the year are turned upside down in a kind of grotesque danse macabre of the end of painting.

The trustees of the Art Gallery of NSW have selected 57 portraits as finalists for this year’s Archibald Prize, with the winner to be announced next week.

The carnivalesque vortex is so strong that even criticism is carried along in the intoxication. The most searing excoriation simply becomes part of the burlesque entertainment, like a court jester mocking the king with impunity. Ultimately, we all become complicit in the media circus, playing our various parts as breathless spruikers or as sardonic hecklers.

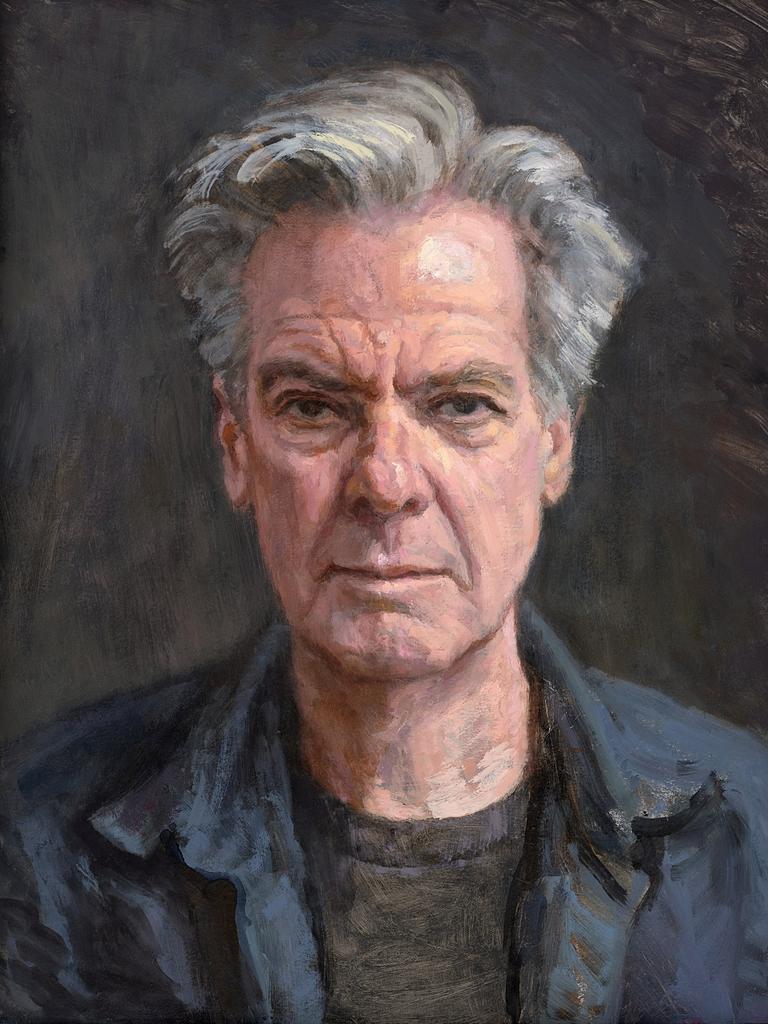

This year, however, I am in the novel position that my wife, Michelle Hiscock, perhaps better known as a landscape painter, is included with The Songwriter, a portrait of Don Walker, who embarked on a solo career after achieving fame writing for Cold Chisel, and who happens to be launching a new album next week.

Her portrait of Walker is a small but direct and intense picture, with an unmistakeable sense of connection with the sitter and his living character. But, of course, a painting like this would be most unlikely to win the prize, because it is straightforward, free of gimmicks, and of a middle-aged white man, which implicitly disqualifies it in an age of identity fetishism.

This picture is among the small group of solid portraits that are selected each year to set off the farcical ones included for the entertainment of the punters.

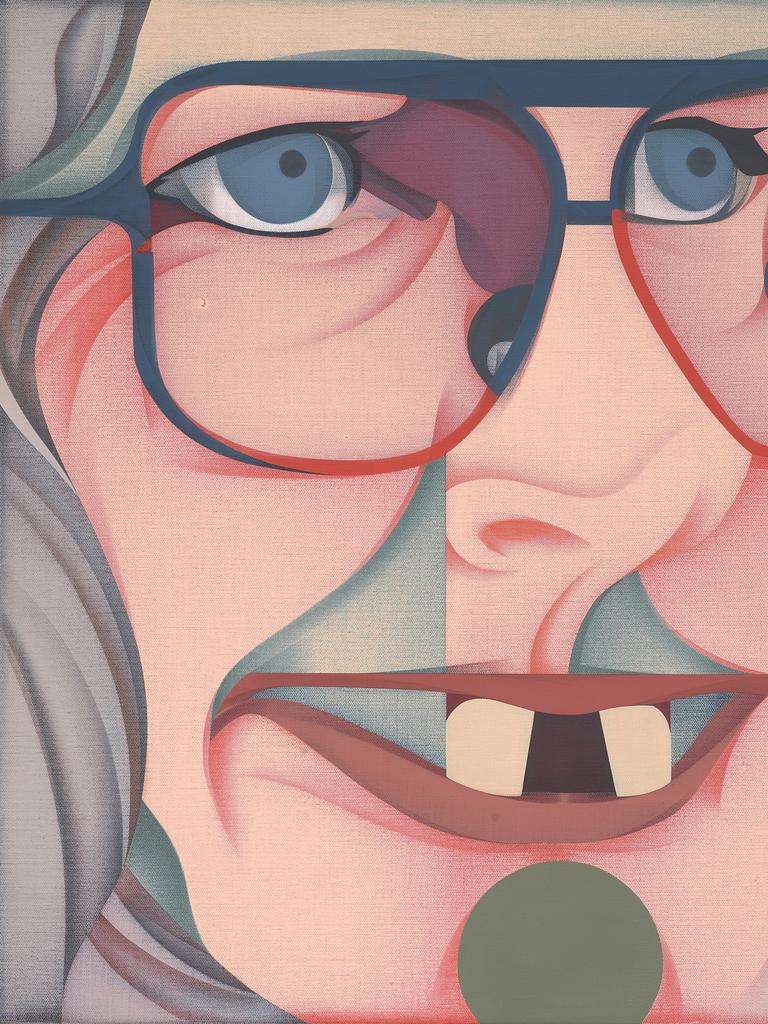

The gallery trustees know that the average visitor pays for the pleasure of gasping at the provocative distortion of Mitch Cairns’ Elizabeth Pulie, or at the excess of David Griggs’s self-portrait titled The Melanoma and the Stitches, and that they won’t be able to see how extreme these aberrations are, and enjoy them to the full, unless there is also some benchmark of accomplished painting in a picture such as Paul Newton’s portrait of John Symond.

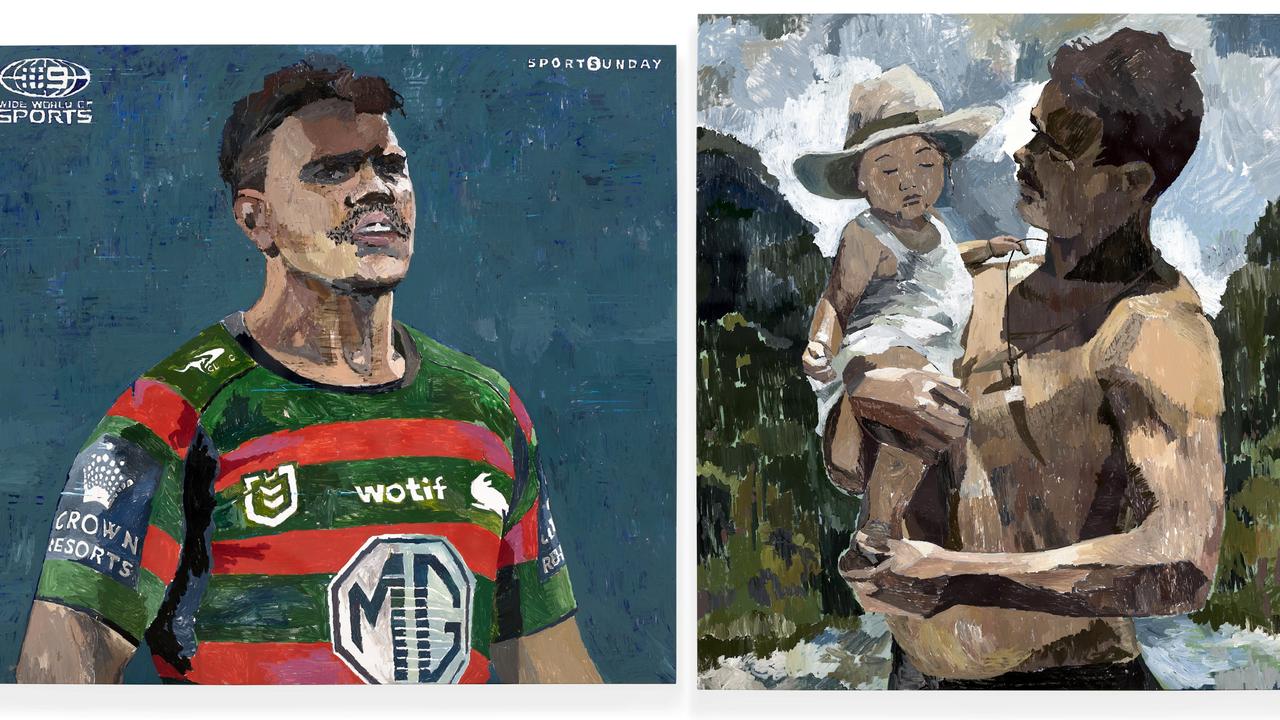

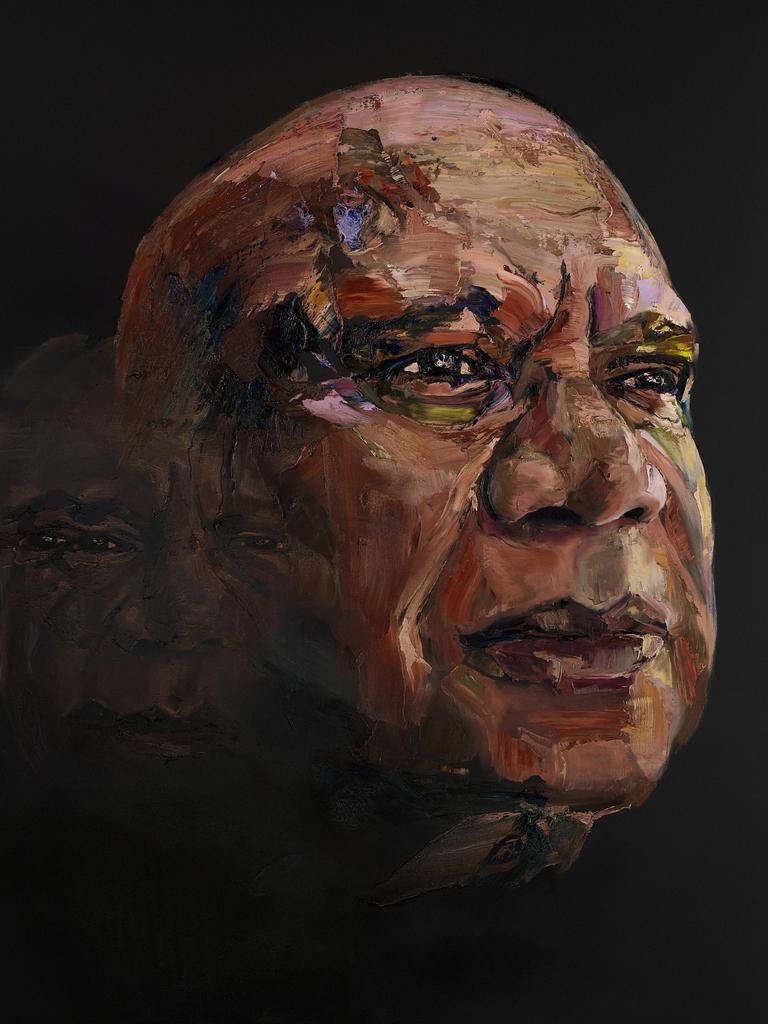

On the whole, this year’s exhibition is almost free of the colossal heads that once haunted it – one survivor is Anh Do’s huge painting of Archie Roach – and even of the hyper-photographic pictures that have been common more recently and have tended to carry off the Packing Room Prize.

There are of course still a few pictures such as Matt Adnate’s oversized portrait of Daniel Johns and Jaq Grantford’s portrait of Noni Hazlehurst, Through the Window, with its suspicious water droplets.

Among the better pictures are Keith Burt’s Sam Leach in his Studio Chair, David Fenoglio’s Christopher Bassi, Tsering Hannaford’s Nanna Mara, Marie Mansfield’s Ronni Kahn, Lewis Miller’s self-portrait and Sally Ryan’s Year of the Rabbit, a portrait of Claudia Chan Shaw. There is also a small but intriguing double portrait by Marcus Wills.

In contrast, why do people think, like Melissa Clements with In the Driveway, 40 degrees, that it’s a good idea to turn a frowning, half-shadowed image of one’s features seen through a car windscreen into a formal portrait?

And why do famous people allow themselves to be painted in pictures that do not do them justice, like Sydney MP Alex Greenwich in the portrait by Jason Jowett – it’s never a good sign if you walk past the painting of someone you have met without recognising him – or Claudia Karvan in an oddly green portrait by Laura Jones?

And why would one of the most intelligent women in Australia, Michelle Simmons, allow herself to be painted as an oversized figure in lurid red and blue and in a literal but mediocre likeness?

Famous people are often approached by artists looking for a likely subject for an Archibald portrait, but they should study the artist’s work carefully and consult knowledgeable friends before entrusting their image to someone who could caricature it.

As for which picture will win the prize, that is not something I ever try to guess or predict; when you think that the same people who made this selection will be also choosing the winner, it should be clear that no result could be too unexpected or perverse.