Shark coughs up gruesome clue in bizarre 1935 murder case

THE crowds had gathered for the thrill of a close-up view of the aquarium's new tiger shark. Instead they witnessed a horrifying event that triggered a murder probe.

Our Criminal History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Our Criminal History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

EVEN a one-tonne shark can bite off more than it can chew.

Or so it seemed to the horrified crowd that had gathered to see a Sydney aquarium’s newest attraction on Anzac Day, 1935.

As the spectators watched on, the frenzied 3.5m Tiger shark began to whip up and down its Coogee pool.

Suddenly the creature regurgitated a human arm.

The tattooed limb still had a rope tied around its wrist.

The shark had been caught after it ate a smaller shark already hooked by the Coogee Aquarium owner’s brother and professional fisherman, Bert Hobson.

Last rites: How a cop faced off with a hitman and survived

Shooting horror: Little girls lost in suburban slaughter

The police were called in and it soon became clear from the knife incisions on the arm that this was no shark attack victim.

But with only the severed arm as evidence, they faced the daunting task of trying to work out who the victim was and how they met their grisly end.

The investigation would lead police on a trail of blackmail, murder, fraud – and a bizarre pursuit across Sydney Harbour.

To work out the identity of the “arm”, the latest forensic advances of the day had to be employed.

Using a technique that had only been tested once before in Australia, the fingerprints were delicately cut off the bloated hand and made into a human glove so they could be properly inked and lifted.

Only two prints were able to be used, but police were hopeful the victim’s prints would be in their files.

After comparing countless records against these prints, police managed to match them to a small-time criminal, James “Jim” Smith.

Edwin Smith, Jim’s brother, also came forward to give a positive identification when he recognised the arm’s distinctive tattoo of sparring boxers in a Sydney newspaper.

Jim Smith was known to police for his involvement in insurance fraud, illegal gambling, and drug trafficking.

He was also a police informant, but this fact would not be made public until many years later and long after the police investigation and coroner’s inquest had concluded.

Two very different characters emerged as key figures in the investigation: master forger, Patrick “Paddy” Brady; and Reginald Holmes, a well-off churchgoing businessman who ran a family boat-building business at Lavender Bay.

Brady and Smith were long-time friends and had been seen in a Cronulla pub on April 8 – the last time Smith was ever seen.

On April 9, according to a taxi driver, Brady had made a suspicious 30km taxi trip to the house of Holmes, looking nervous and carrying a small kitbag.

Brady had been renting a cottage in Gunnamatta Bay, and the cottage’s owner would later complain a mattress and trunk had been replaced, the walls cleaned and a rowing boat appeared to have been scrubbed.

Holmes was a dubious figure himself, with reputed links to drug smuggling and insurance fraud.

He also was connected to Smith through at least two frauds – a building scam in 1929, and a botched insurance claim in 1934. In the latter case, a witness spotted Smith rowing away from a burning yacht that was owned by Holmes.

Brady became the prime suspect in what police now believed was a murder. But they still did not have a complete body, had no clue as to a motive, and no-one willing to give up information.

When quizzed, Holmes denied knowing Brady. And Brady, his wife and young son remained mute through hours of police interrogations.

Police finally tried to make Brady talk by arresting him on May 19. But when Brady was charged with the murder, it was Holmes who would eventually crack under the pressure.

He responded to the news by driving his speed boat – one of the fastest in the country at the time – into Lavender Bay and trying to shoot himself in the head.

But he only succeeded in wounding himself. Then his arm became entangled in a rope as he tumbled from the vessel and hit the water.

Holmes, possibly revived by the unexpected dunk in the briny, climbed back aboard and spent the next four hours speeding around Sydney Harbour.

After weaving through mid-morning ferry traffic with police on his tail for hours, Holmes surrendered and was admitted to hospital under police guard.

He was now ready to reveal what he knew of Smith’s murder.

Holmes told police that Smith and Brady had been blackmailing him for some time.

On April 9, Brady had arrived at his house, showing him Smith’s severed arm in a brown leather kitbag.

He said Brady had later thrown the arm into the sea at Maroubra Bay.

Holmes also agreed to give evidence against Brady at a Coroner’s inquest.

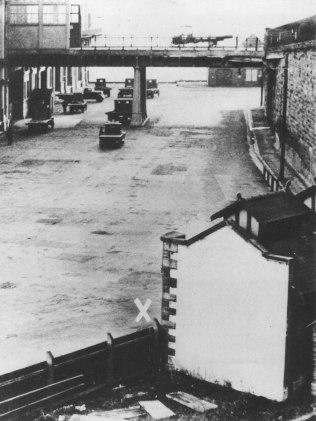

But on the morning of the inquest, Holmes’ body was found slumped over the wheel of his car at Millers Point docks, with three bullet wounds to his left side.

Investigators would come to believe it was not another murder, but a suicide.

Holmes’ death derailed the case against Brady over the murder of Smith. He was set free, and the case left unsolved.

The rest of Smith’s body has never been found. Some believe it to be in a metal trunk at the bottom of Gunnamatta Bay.

But there are those who doubt Brady was the killer.

Renowned legal historian Professor Alex Castles, who probed the case in his 1995 bestseller, The Shark Arm Murders, didn’t think there was a persuasive case that Brady killed Smith.

Prof Castles found no evidence Brady was a violent man and doubted he was physically capable of single-handedly killing Smith, an ex-boxer.

And above all, he had no motive for killing his long-time friend.

In another twist, he believed Holmes actually arranged and paid for his own murder – paid for with the 500 pounds he withdrew from a bank account on the afternoon before his death.

What only a few people knew at the time was that Smith had been a police informant, and had caused the arrest of a violent bank robber, Eddie Weyman.

Brady lived for 30 more years, and continued to claim his innocence.

Whatever knowledge he had of the mysterious shark arm murder, he took to his grave.

- This is an edited version of a story first published in September 2012

Originally published as Shark coughs up gruesome clue in bizarre 1935 murder case