How a cop survived being shot by an underworld hitman during a bank heist

NOT many people survive receiving the Last Rites from a priest. Even fewer face a stone cold underworld killer’s gun and live to tell the tale. But Melbourne cop Michael Pratt did.

Crime in Focus

Don't miss out on the headlines from Crime in Focus. Followed categories will be added to My News.

NOT many people survive receiving the Last Rites from a priest. Even fewer remember the experience. Then again, Michael Pratt isn’t an ordinary guy.

More than 40 years ago, he took on a gang of three armed robbers without a gun of his own and almost died when he was shot in the back trying to prevent two from escaping back in 1976.

His survival is all the more amazing considering the man who shot him would later go on to become a hitman during Melbourne’s infamous gangland war, gunning down several key players in that conflict.

WINNERS AND LOSERS OF BANK ROBBER FASHION

UNSOLVED MELBOURNE CRIME THAT BAGGED MILLIONS

Mr Pratt became one of Australia’s most highly decorated policeman when awarded the George Cross — Australia’s highest award for civilian bravery.

An extraordinary day

Michael Pratt was a young constable at Heidelberg police station. He joined the force as a cadet in February 1973, and was posted to Heidelberg after stints at Russell Street and on CBD traffic duty.

The most extraordinary day in his life — Friday, June 4, 1976 — started out quite mundane.

“I was off duty and going to my uncle’s. He was a barber in Queens Parade, Clifton Hill. I was going to get my hair cut,” Michael says.

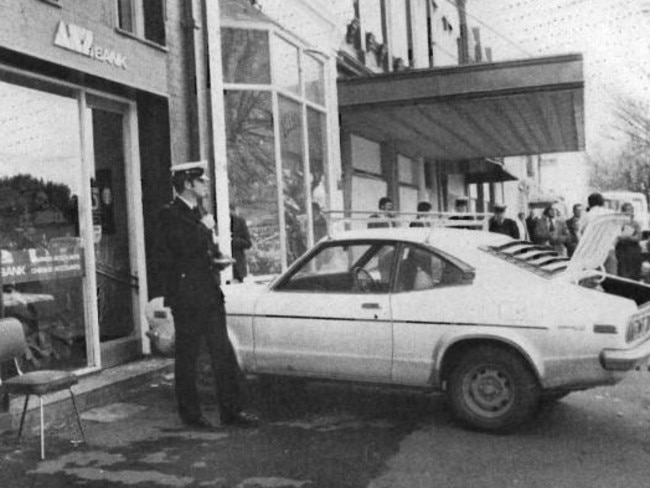

He spotted three men with scarves, balaclavas and handguns entering the ANZ Clifton Hill branch as he waited to turn right from Heidelberg Road into Queens Parade.

Michael, 21 and married to Dianne for just three months, reacted immediately.

“I thought, ‘Oh well, these blokes are obviously going to rob the bank, so I’ll do something about it’,” he says.

He drove his Mazda 808 across the intersection, mounted the kerb and blocked the bank entrance, grabbing a jack handle for protection and ordering a nearby worker to phone police.

“I’m standing beside the car. There’s one inside the bank door, and he’s got a silver .22 pistol. He’s pointing it at me to move the car, and I thought, ‘Well, stick it up your arse’, you know,” he says.

“Another bloke is up on the bank counter fanning the gun over the people. The manager and a customer he had in his office ran to the back of the bank. (The gunman) has let one go (fired), and it hit the woodwork around the door at head height.

“The other one was in the tellers’ cages and he’s yelling out to the bloke in the door, ‘Shoot him! Shoot him! Get him out of the way!’ about me.”

Michael stood his ground. “They’ve then decided to come out. The bloke on the counter thought, ‘I don’t like this’. He’s jumped down and ran out the back door,” he says.

Michael’s car wedged the front door shut as the two remaining robbers tried to flee.

“Next thing you know, a leg has come through the glass and smashed it, and that freed up the frame. One’s come across the bonnet of the car, and I’ve grabbed hold of him,” he says.

“Quite a violent struggle ensued. I got a few good ones in, and so did he, but he’s gone down in front of me, semiconscious on his knees, and the other one is standing with his arms stretched out with a .38 Wembley, saying, ‘Don’t move, or I’ll shoot’.

“The bloke I tackled was starting to get up. I grabbed him in a bear hug thinking the bloke with the gun won’t shoot for fear of hurting his mate, but he (the gunman) got behind me and let one go into my back from about six feet.”

Michael says the pain was unbearable. “It was like a sledgehammer in the back and I went down face first. They ran off to a car. I could hardly breathe. It felt like somebody standing on my back and jumping up and down.”

‘I’m drowning in my own blood’

The bullet entered around Michael’s left shoulder blade, missed his heart but brushed his aorta, leaving a burn scar on the artery wall.

It punctured his left lung, ricocheted off his sternum and struck his spine, leaving a neat hole in the thoracic section, before it stopped inside his right lung.

The bandits fled with just shy of $5000 — later ruined by a dye bomb.

Michael was rushed to St Vincent’s Hospital. He was drifting in and out of consciousness, but he remembers one doctor’s life-saving intervention.

“Their top surgeon comes down with his team, and they’re doing all the vital signs and everything. Next thing I knew, one of his young doctors is up on the trolley, kneeling over me, and he’s got a scalpel.

“He’s gone (Michael motions incisions in his upper chest) and all this blood came out all over my shoulder and everywhere. A tube was put into my lungs and they pumped out a pint and a half (750ml) of blood from my left lung. The young doctor’s realised I’m drowning in my own blood.”

Michael says a priest visited him. “He had all the gear on and he was giving me the Last Rites. And I thought to myself, ‘I think I’m in trouble here’,” he says.

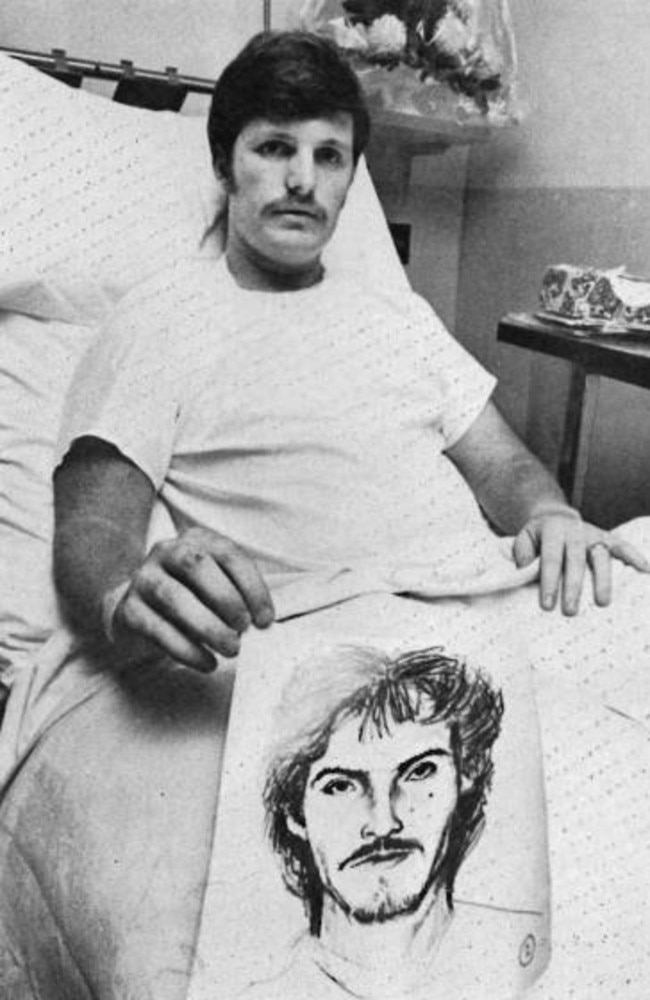

The following morning, after five hours of surgery, detectives from the Armed Robbery Squad arrived.

“From the camera stills from the bank, they had a rough idea who it was. They produced a photo board, and straight away I pointed to the man that shot me because his disguise had fallen down a bit and I got a good look at him,” he says.

“They took a dying deposition from me just in case I didn’t bloody make it, because I found out later I wasn’t expected to last beyond Saturday night.”

Shooter arrested, but little justice

Miraculously, Michael was moved from intensive care to a general ward at St Vincent’s four days after shooting, then to the police hospital in South Melbourne by the weekend.

Six days later, he went home and returned to a desk job in Heidelberg the following month, although crippling back pain forced him to take leave soon after.

“The best thing for me was that the bullet was a flat-nosed practice round, not a jacketed round, and it didn’t get a chance to mushroom out. If it did, it would have torn my aorta out. It just left nice, neat holes on the way through,” he says.

Members of the gang were rounded up little more than a week after the robbery, hiding out the garage of a house in Coburg. They escaped with about $4900 but a dye bomb ruined the loot.

The robber who shot him, who can’t be named, had already killed a man in the month before the robbery. In prison after his arrest, he killed another.

He was given jail terms for manslaughter — and when he was sentenced for the crimes committed during the robbery including the wounding of Mr Pratt, he received only a few extra years in jail.

When he was released from jail he became a key figure in Melbourne’s underworld conflict between drug kingpin Carl Williams and members of the Moran crime family, taking part in several executions.

The George Cross

Michael returned to work again in February 1977 but the pain remained. A specialist, Jonathan Rush, found the cause — that hole in Michael’s spine. It was hard to spot without the CAT scan technology we have today, but was found using a composite of X-ray images.

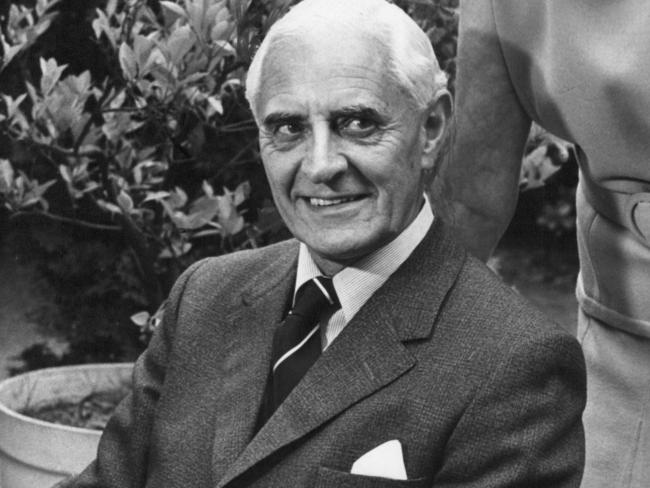

Rush referred him to a man with great experience in similar wounds, Sir Edward “Weary” Dunlop.

“He said he hadn’t seen an injury like that since the war. He was a wonderful man. He sat down and spoke about the power of the mind. I get a bit upset about this,” Michael says, becoming emotional.

“He said, “I had men in Changi with no morphine or anything. They beat the pain with the power of the mind. I tried the things he said, and I got over it.”

As Michael grappled with his injuries, he was recommended for the George Cross, an honour granted by Queen Elizabeth — a civilian equivalent to the Victoria Cross.

Sir Henry Winneke, Victoria’s Governor, presented the award to him at Government House in November 1978.

“It was a privilege to get the George Cross. It was totally unexpected. On the day, you did what you did. You don’t do it for medals. You’ve just got to be in the wrong place at the right time,” he says.

Michael again returned to work in the force’s public relations unit, struggling with pain and emotional issues following the shooting.

The Police Medical Officer forced his retirement in July 1979. “I was only there I reckon less than 30 seconds and he said, ‘You’re finished son, you can’t be a policeman’. It wasn’t well received by me,” Michael says.

Michael appealed directly to then-Chief Commissioner Mick Miller, without success. “I think he relied on advice. Doctor knows best,” he says.

While there was little official support from the force, his police mates kept him close. “If I had a dollar for every police car that stopped in my driveway or every phone call over the years, I’d be a very wealthy man,” he says.

‘The pressure doesn’t change’

In the ensuing years Michael worked as a delivery driver, a TAB security consultant, a communications officer for Intergraph (a private firm that once ran Victoria’s emergency service communications) and ran his own pizza shop before returning to the force in a supporting role in 1996.

Michael became a police administration officer, working in police stations. These days, he works at his local station on Melbourne’s outer fringe.

“I quite like what I do. Some people say that I’m inside all the time, doing the admin, but I’m pretty close to the action without being there,” he says.

“I get on well with the young coppers. I can give them a bit of advice here and there and I listen to what they think.”

He’s also a peer support worker, helping them to seek support when the job overwhelms them and drawing on his own police experience.

“That side of it is quite rewarding, helping out. I worked with a lot of blokes over the years. You saw things go wrong, and the pressure they were under. The pressure doesn’t change from then to now. Car accidents, family violence, suicides, or dead bodies. It takes its toll.”

Michael and Dianne had four children — Stephen, Danielle, Amanda and Michelle — and now have 11 grandchildren.

He also stays busy with official duties as part of the Victoria Cross and George Cross Association — a group of people bonded by their incredible bravery in life-threatening situations.

He speaks often at public and private functions, in schools, at meetings of services clubs and at police events with a message of leadership, personal responsibility and the element of bravery he says can be within all of us.

He has visited England at least 16 times since he was awarded the George Cross for official reunion events with other members of the association.

He, Dianne, their three daughters and his parents have met the Queen and most members of the royal family. He speaks warmly about them — like old friends.

Michael says the George Cross has afforded his family rare opportunities.

“It meant quite a bit, but it meant a lot more when I went across to London for my first Victoria Cross/George Cross reunion in 1981 to see all the medal holders,” he says.

“I met all the VC and George Cross holders. I admired all of them, and they’re saying to me, ‘I admire what you did’. I didn’t think I was in their company at first, but they put everyone on the same level there.

“Stephen hasn’t ever chosen to come over with me, but it was the making of my girls. Seeing all those people and the confidence they got from meeting the Queen and the Queen Mother and all those wonderful people.”

KILLERS WHO THOUGHT THEY GOT AWAY WITH MURDER

THE SAVAGE MURDER THAT SHOCKED VICTORIA

Originally published as How a cop survived being shot by an underworld hitman during a bank heist