How corrupt cop Roger Rogerson led to birth of Undercover Branch

The shooting of former drug squad officer Mick Drury is well known. What isn’t known is how his shooting — allegedly organised by corrupt colleague Roger Rogerson — led to the birth of the NSW Undercover Branch. EXCLUSIVE AUDIO

True Crime

Don't miss out on the headlines from True Crime. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Previously in Undercover, we revealed how operatives infiltrate gangs and pose as criminals to elicit confessions and damaging evidence. Now, in Part III, we reveal the untold history of the NSW Undercover Branch, and how it all started — with Roger Rogerson.

Undercover operations are a relatively recent tactic in law enforcement. Until the late 1980s, there was no formal training program or dedicated branch. There were no welfare checks or debriefing sessions, psychologists or supervision. The work was ad hoc; operatives winged it. “We learned on the streets,” said Mick Drury, the former operative who was nearly killed because of his undercover work.

“The excitement of it was that you didn’t have to chase them for the evidence. They brought it to you.”

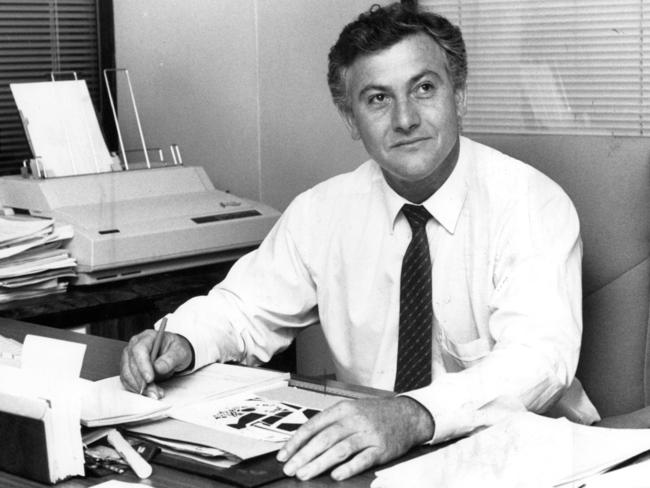

Drury made his name as an honest cop in a Force full of corrupt, dishonest men. He is a large man with a gentle smile and small, stylish eyeglasses that lend him the look of an art critic, rather than a “substantial underworld figure”, the role he played during his years undercover. That was during the 70s and 80s, long before the formation of the Undercover Branch he helped establish.

“Occupationally, you are very isolated,” he said. “It’s a very tough vocation.”

Drury became the architect of Australia’s modern undercover policing program through what he calls a “serendipitous circumstance” with a man his exact opposite: Roger Rogerson, the deeply-corrupt former police officer, then a colourful, decorated detective sergeant with hero status among colleagues.

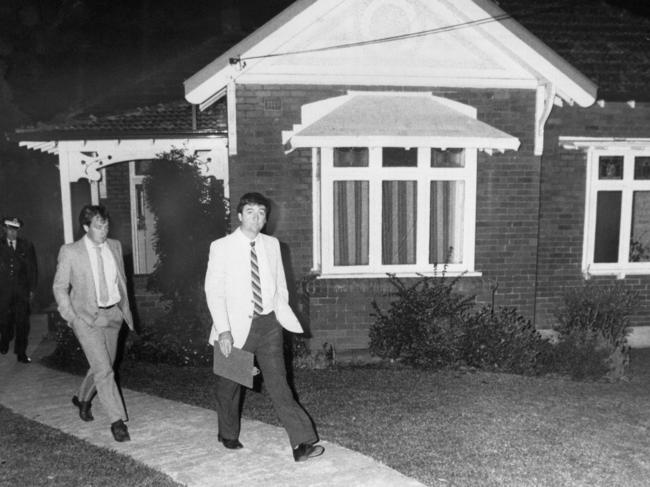

On the night of June 6, 1984, the undercover Drug Squad officer was in his kitchen washing dishes when a gunman appeared through the window and shot him twice in front of his family.

Few people expected him to live. Twelve days later he woke from his coma and gave a dying deposition to detectives, naming Rogerson as the brains behind the shooting.

Drury said Rogerson had offered him a bribe to change his evidence in court against a heroin dealer, Alan Williams, and his refusal to do so became the motive for the shooting.

“They tried twice and they missed,” is all Drury will say about the matter, referring to a second assassination attempt that followed, which he prefers not to speak about.

(Rogerson was acquitted of the Drury shooting in 1989 and is currently serving a life sentence for the 2014 murder of a drug dealer, Jamie Gao.)

Realising the threat to Drury’s safety, the Police Commissioner, Jack Avery, arranged a job for him at the Australian Consulate in Los Angeles to get him out of the country.

“My life was in danger and a decision was made to send me overseas until they got on top of it,” Drury said.

He’d been in his new role barely three months when, one day, his desk phone rang; it was his old boss at the Drug Squad, Jim Willis. Willis had become concerned about the quality of his unit’s undercover operations, saying they had no oversight, no accountability, and little duty of care for the staff. At the time, undercover work was piece-meal; many units did the work, but there was no formal training, information or co-ordination.

“We taught ourselves, it was madness,” said Drury, who returned to Australia in 1988 armed with the latest techniques from the world’s best: the FBI, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, the LAPD, and the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency. He went on to adapt the techniques and wrote the first formal pilot program for undercover operatives, teaching it to police forces around the country, along with the AFP, the Royal Hong Kong Police Force and ASIO. (The Undercover Branch’s current commander, Henry, confirmed that he was one of Drury’s students.)

For the next few years Drury acted as a kind of consultant on undercover operations; cops would come to him for advice and direction. Most memorably, he was asked about a serial killer dumping bodies in the Belanglo State Forest. Detectives working the case approached him with an idea to send two operatives down the Hume Highway dressed as hitchhikers, hoping to entice the killer to abduct them. A helicopter, the detectives assured him, would follow the operatives overhead to keep them safe.

“It was too dangerous,” Drury said, pointing out several problems with the plan. First, the killer was immobilising multiple victims at once and no one knew how he was doing it; it was either at gunpoint or using a gas, possibly when he stopped to refuel the vehicle. “We didn’t know if (he) was just taking them in the car and shooting them.” Second, no one knew what time the victims were being abducted, or where along the highway this was taking place.

And third was the helicopter itself. “It runs out of fuel,” he said. “A two or three minute delay would be enough to kill the operatives.”

The operation ultimately didn’t proceed, but the serial killer — Ivan Milat — was eventually caught using old-fashioned techniques. (A significant breakthrough occurred when an Englishman, Paul Onions, who’d escaped the cab of Milat’s truck and ran to safety, saw a news report about the murders from the United Kingdom, and contacted NSW Police with crucial identifying details.)

Undercover policing grew out of this heady, sepia-tinged era, a time of endemic police corruption, external reviews, and a royal commission set up to expose the root causes. Operations were slapdash at times, leaving operatives exposed to extreme risks and near-death experiences. In Kings Cross, a female operative survived a drug-rip when a .357 pistol, pressed into her skull, miraculously malfunctioned and wouldn’t fire. In a separate case, an operative working on the NSW/ACT border was kidnapped by drug dealers, gaffer-taped and held for ransom until colleagues eventually got him back alive. “That’s all it takes,” said Drury. “One question, one remark, one wrong move.”

Disasters of this kind are far less likely to occur today, but drug-work remains undeniably fraught with danger for operatives around the country. “I subscribe to the theory of continual improvement,” said Henry, the Branch’s commander, when I asked him about one case in particular. “We need to learn from cases that didn’t go well,” he continued. “Like Tapiola.”

Strike Force Tapiola. A 2007 drug buy at Wetherill Park for $28,000 worth of PMA. The targets were known to be extremely dangerous; a few nights earlier they’d raided a house, fired a shotgun, and pointed the barrel at a child. The operative would have this same gun shoved into his face. As the men demanded his cash, he uttered a distress code and hit the deck as heavily-armed officers stormed the scene, firing ferret rounds into the getaway car.

This is one aspect of drug-buying that cannot be removed from the risk equation — the leap of faith required between dealer and buyer, the target and police; neither will ever know if they’re being set up for a robbery, an arrest, or something more sinister. “They’re not scared of being arrested,” said Andy MacFarlane, the former operative. “They’re scared of you coming to rip off their drugs.” But for operatives, the risk is the same, he warned. “They (the dealers) know we’re turning up with $500,000,” he said. “You can’t get that out of an armed robbery anymore.”

THE CANADIAN METHOD

One tactic remains controversial, a Canadian invention developed in the 90s that still draws intense scrutiny around the world, including in Australia.

It’s a technique with many names, but to preserve its effectiveness only bare details will be laid out here. Put simply, an operative poses as a criminal, works for months to gain their target’s trust, and if the investment pays off, the mark will confess the full details of their crime. It’s a risky, time consuming, and expensive tactic, but without it some of the country’s most high-profile homicides would remain unsolved, including that of six-year-old Kiesha Wieppeart, reported missing by her mother in 2010, and 13-year-old Daniel Morcombe, who disappeared from the Sunshine Coast in 2003.

Australian courts, unlike Canadian courts, are deeply-protective of this technique, so it’s difficult to know how many times it’s been used successfully.

It’s been deployed at least 12 times nationally since 2003, but in some cases, judges have refused to allow the confessions. In one case a NSW woman with a mental illness, Patricia Gallagher, was found not guilty of murder in 2013, in part because of how operatives gleaned her admissions.

Another young man, Tony Simmons, was found not guilty of murder because his confession was ruled to be no more than ‘big-noting’.

Canadian police have used the technique hundreds of times, but the country’s High Court recently revised its position on the tactic, sending shockwaves through the worldwide fraternity of undercover operatives. Confessions must now be considered “presumptively inadmissable” in Canada, unless the state can prove the target wasn’t under duress, or big-noting at the time. For now, Australian courts are not applying this same standard, though some argue it’s strengthened the technique and led to stronger convictions. “The sky hasn’t fallen in,” said Emma Cunliffe, Associate Professor at the University of British Columbia School of Law. “This technique has value, but it should be used with care, and it should not become a basis on which the police engage in activity that could bring them into disrepute.”

‘I HELPED HIM GET RID OF THEM’

Unsurprisingly, some criminals who’ve fallen for this technique are scathing of how police use it. One such critic is Terry Mark Donai, currently serving a 40 year sentence for the murders of Pamela and William Weightman on January 9, 2000.

“Everything about my case stinks,” Donai wrote to me from prison.

“The police didn’t care if I was innocent or not — they were only after a conviction.”

The Weightman case was originally ruled a car accident. Their bodies were discovered inside a Mitsubishi Magna that crashed down an embankment in the Royal National Park at Heathcote. Family members urged a review and, upon reflection, the pathologist revised his ruling on the cause of death, calling it ‘undetermined’. For years, the case remained shut.

Then in 2004, almost four years after their deaths, a relative desperate for answers confronted the Weightmans’ adopted son David. Asked if he killed his parents, the 20 year old blurted out a confession and named Donai, an acquaintance, as the person who carried out the crime. (In exchange for his co-operation, David received a 22 year sentence, which he is still serving.)

Donai soon became the target of a lengthy undercover investigation. A man named ‘Jack’ suddenly entered his life, offering him menial jobs in private security where Donai was trying to get a foothold. Simple surveillance jobs soon developed into more complex, dangerous tasks. Jack made it clear he was involved with dangerous people, a gang of well-connected individuals, almost like a mafia family. “By this time I believed I was in too deep after some of the things I had seen,” Donai wrote. “I feared for my safety, my family’s safety.”

Seven months after the operation started, Donai met with ‘John’, the supposed head of this syndicate. “Is there anything you wouldn’t be prepared to do with us?” John asked. “Like, where would you draw the line?”

“I’d never kill a child,” said Donai. “That’s about as far as I’d draw the line.”

John approved, but told Donai there was a problem: he was too hot. There were rumours about police attention, about the Weightman murders. He’d have to come clean if he was going to be accepted to the brotherhood.

“I helped him get rid of them,” Donai uttered. “That was it,” he said, though a jury doubted this story, convinced he was severely underplayed his role in the crime.

He was handed two life sentences for, but these were reduced on appeal to a 40-year maximum sentence. His third appeal, to the High Court, failed in 2017. “The jury got it wrong,” he wrote.

Originally published as How corrupt cop Roger Rogerson led to birth of Undercover Branch