Breaking Badness: Gary Jubelin goes face-to-face with prison inmates at Macquarie Correctional Centre

Former cop Gary Jubelin used to lock prisoners up and never thought about them again as he moved on to the next case. Now he has been granted full access to a maximum security jail and what he found shocked him.

Breaking news

Don't miss out on the headlines from Breaking news. Followed categories will be added to My News.

I walked into maximum security prisons hundreds of times in my career as a detective, but

I’d never felt this exposed.

During those previous visits I was kept separate from the crowd of prisoners because they hated the police and there was a real potential for violence.

This time I was going in as a journalist to record a new podcast called Breaking Badness. I’d been given permission by Corrective Services NSW to access all areas of the Macquarie Correctional Centre in Wellington in the state’s west, and to mix freely with the inmates.

Meaning, for the next couple of weeks, there would be no restraints. No fences between us.

And few prison officers around to help out if things started to go bad.

As I was being searched and scanned on the first day, the prison officers told me, ‘We just don’t know what these guys will do when they realise who you are.’

One of the producers I worked with on the Breaking Badness podcast later told me he was watching out in case somebody threw a chair, or worse.

PRESS PLAY BELOW TO LISTEN TO EPISODE 1 OF BREAKING BADNESS

Listen to Breaking Badness on Apple Podcasts RIGHT HERE and subscribe to CrimeX+ today

Nor was I sure anyone would talk to me. Crims hate coppers and there was every chance they’d turn their backs and refuse to engage.

So it’s fair to say I was nervous. But there was no way I was going to show fear.

The reason for me going to Macquarie was personal. After leaving the police, I’ve started to look at the world of crime and punishment differently.

My job as a major crime detective was to lock up the bad guys. I didn’t care what happened to them after.

Often, there wasn’t time to think about it. I just moved onto the next case.

That changed after I met a notorious crook called Bernie Matthews, a former armed robber and serial prison escapee.

Over his life, Matthews spent about three decades inside, which is as long as I was in the police.

In 1978, he was pictured on the front page of this newspaper under the headline ‘The brutes of Katingal’ after being locked up in Australia’s first super-maximum security prison.

Yet, shortly after his release a few years ago, we became friends.

I visited him in hospital before his death in 2021 and on his death bed he told me, ‘Gary, if they treat us like animals in prison, we come out like animals.’

That got me thinking about what occurs behind those high concrete walls and steel gates.

I found myself asking, what if prisons have become a place where people go in bad and come out worse?

I started looking more closely and discovered that half of those who are released from prison in New South Wales end up back inside it within two years.

Meaning prison isn’t working. Or at least the way we do it at the moment doesn’t work.

I got talking to some senior corrective service officers and was impressed by their passion.

They wanted to make a difference.

They told me about the Macquarie Correctional Centre and, at first, I couldn’t quite believe what they were saying: Allowing maximum security prisoners to live in dormitory accommodation, not locked in cells.

Giving them art classes, gym equipment and luxuries like shower products straight up, not making the prisoners work to earn these first.

Aren’t prisons there to punish criminals? I asked. It seemed like a recipe for disaster.

Those conversations led to an invitation to visit and have a look for myself.

On my first morning in Macquarie, I was shown to a room full of hardened prisoners.

These were men who had committed the worst crimes, including gang members, murderers and drug manufacturers.

At least one of them, I found out later, had been arrested by detectives I was supervising.

I told them I understood they might not like me. Slowly, they started to open up.

The conversation went backwards and forwards, talking about how the way they were treated with respect inside Macquarie made them feel more human.

And how that meant they’d be better able to reintegrate when they were released back into society.

Because one day, they are going to be released.

At one point, a prisoner asked me, ‘Do you think you would be walking out of here in another prison?’

I looked around and realised I was in the centre of the room surrounded by the prisoners.

There was one officer, standing against the back wall.

I understood the message – I was in their world now. It would be very easy for them to give me a flogging or worse. In another prison, that might have happened.

But in Macquarie, this prisoner was saying, respect is given to the prisoners and they give respect I return.

Afterwards, it still took a long time before I started to feel comfortable inside Macquarie.

Like any maximum security prison, it is an intimidating environment.

There are high walls covered with razor wire, clanging metal doors, thick steel bars and groups of big, tattooed men dressed in their prison greens.

There were some threats, and some black humour with me as the target.

But there was also something else. Something I couldn’t put my finger on at first.

Inside Macquarie, I experienced things I never expected.

Like sitting with a group of the prison heavies as one came close to tears talking about how coming here had helped him rebuild his relationship with his family.

Some of the other prisoners got up out of their chairs to comfort him. I started to see the person behind the prison uniform.

At other times, prisoners told me how the constant threat of violence in other prisons made them angry, dangerous and anti-social

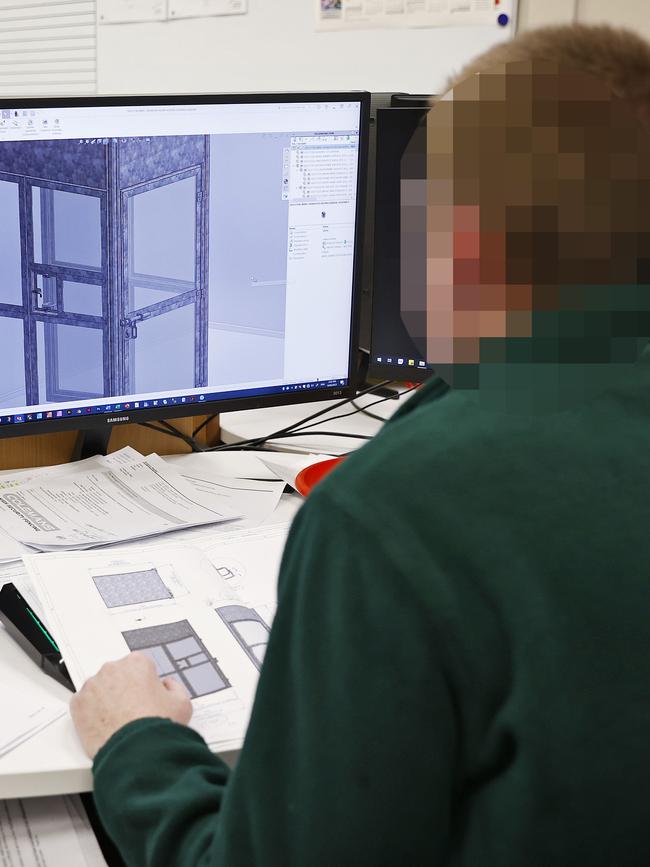

In Macquarie, the inmates work together for seven hours a day, study for another seven, resolve conflicts through discussion and socialise together, just like they would do on the outside.

Anyone who is violent risks being thrown out, back into the old prison system.

I realised what I’d been missing in Macquarie was that looming threat of violence I’d felt in other prisons.

It made me think about who’d you want living next to you, a prisoner who has been released from here or from the old system?

Because they’re going to live next door to somebody after being released.

That said, what they are doing in Macquarie won’t work for everybody.

Even the prisoners I spoke to accepted there are some criminals who cannot be rehabilitated and we need to protect society from them.

But I left the prison with a different view on incarceration to the one I had on the way in.

As a former homicide detective, people might think that means that I’ve gone soft but I haven’t.

If the system that we’ve got at the moment isn’t working, then surely it’s worth trying something else.

Looking back on my time at Macquarie, I think that revealing what’s going on inside that prison might be the most important thing I ever do in terms of crime and punishment.

Bigger than anything I did as a detective.

Bigger than leading the Strike Force Tuno investigation, which investigated multiple murders, shootings, armed robberies, drug offences and led to 14 people being convicted of over 100 different offences.

Bigger than the arrest of the paedophile and murderer Jeffrey Hillsley, who signed his own name ‘Walking Evil’ and had abducted a 10-year-old girl.

Because if what they are trying at Macquarie helps reduce the rate of re-offending, that means there will be less crimes.

Fewer crimes means less victims.

Everybody wins.

Subscribe here to listen to Breaking Badness.

More Coverage

Originally published as Breaking Badness: Gary Jubelin goes face-to-face with prison inmates at Macquarie Correctional Centre