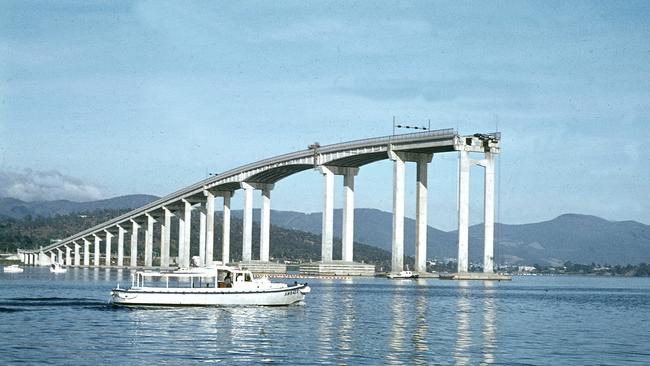

Incat’s Robert Clifford built his Incat empire from the ‘ferry boat shuffle’ which followed the Tasman Bridge disaster

After the Tasman Bridge disaster Hobart needed ferries. That’s where a young Robert Clifford stepped in. See how he went on to build an empire.

Tasmania

Don't miss out on the headlines from Tasmania. Followed categories will be added to My News.

For Robert Clifford the Tasman Bridge tragedy spawned the start of his international ferry empire.

But he vehemently rejects it was a money spinner for either himself or his Sullivans Cove Ferry Company.

“People think we made a fortune,” Mr Clifford said.

“The reality is that we built three boats but by the end of the service, the third boat wasn’t paid for.

“I started off the business with no overdraft, and in the end, I had a bloody massive overdraft to pay for the last boat.

“I eventually sold the boats to North Queensland.

“But for six months or so afterwards, we were really crying poor, trying to find enough money to pay the banks and pay our creditors.”

In 1975, he was 31 and enjoying making “quite a reasonable living” running two ferries across the Derwent with most of the income from daylight and evening charters and lunch time cruises.

“But of course, all that went by the board when we had to run a 24 hour service,” Mr Clifford said.

He’d been to a party on Sunday January 5 and was driving along Sandy Bay Rd when he came across a road block but was waved through when the police officer realised who he was – but he still wasn’t sure what was happening.

He got to his office and when an acquaintance told him about the bridge accident: “I didn’t believe him.”

His two ferries helped search for survivors and the next day his round the clock ferry service began in earnest.

“People were queued for half a mile up the road in Bellerive and we had to tell them ‘no children’ because we needed to get essential people to work first.

“We didn’t charge anyone for the first few days because we just physically didn’t have the ability to take people’s money and maximise the number of people we could get on board as quickly as we could.”

Mr Clifford was reimbursed the fares later by the government but locked horns with the head of the then Transport Commission because he wanted him to charge half of the regular return ferry fare of 50 cents.

“I said ‘like bloody hell’. If that’s the case, well we’ll stop at midnight.

“I rang the Mercury and said, ‘we’re going to stop at midnight’.

“It was about 40 minutes later, and the Premier (Eric Reece) was on the wharf when I got back and said, ‘you can charge what you like, you’ve done a great job’.”

Mr Clifford’s ferry service provided a vital lifeline for the 45,000 people who then lived on the eastern shore – which at the time had few essential services - and faced a long drive to get to the western shore.

The ferries ran on a 40-minute schedule, six minutes apart and “it was busier than ¬Sydney Harbour”.

The 24 hour service was draining for his team of 16 - which grew to 64 – and included his late father as a relief skipper.

“We were exhausted working the long hours and of course at 1am in the morning, when you’d try to get go home to go to bed, and there’s still another 50 or 100 people waiting at the wharf, you couldn’t just leave them there.

“At six o’clock in the morning we had to have three boats in operation because of the aircraft leaving the airport at seven o’clock.”

Ever the astute businessman a week after he began the 24-hour service he told his boat building friends to get the materials for another boat.

“We had one built within six months, a second within 12 months, and a third within two years and then we started on the catamaran to double the work of the other boats at twice the speed,” he said.

“It was all about faster, more efficient boats.”

When he had five boats operating on the River Derwent he estimates he transported more than 9 million people in the more than two years after the bridge collapsed.

The need for more ferries led to the creation of now internationally renowned Incat.

When the bridge re-opened in 1977, ferry patronage plummeted so he turned to building and selling boats.

On the 50th anniversary Mr Clifford said: “One of the overriding memories and thoughts I’ve got now is that out of the 16 crew, and those involved with the company, most of them are now bloody dead. I’m a survivor.”

More Coverage

Originally published as Incat’s Robert Clifford built his Incat empire from the ‘ferry boat shuffle’ which followed the Tasman Bridge disaster