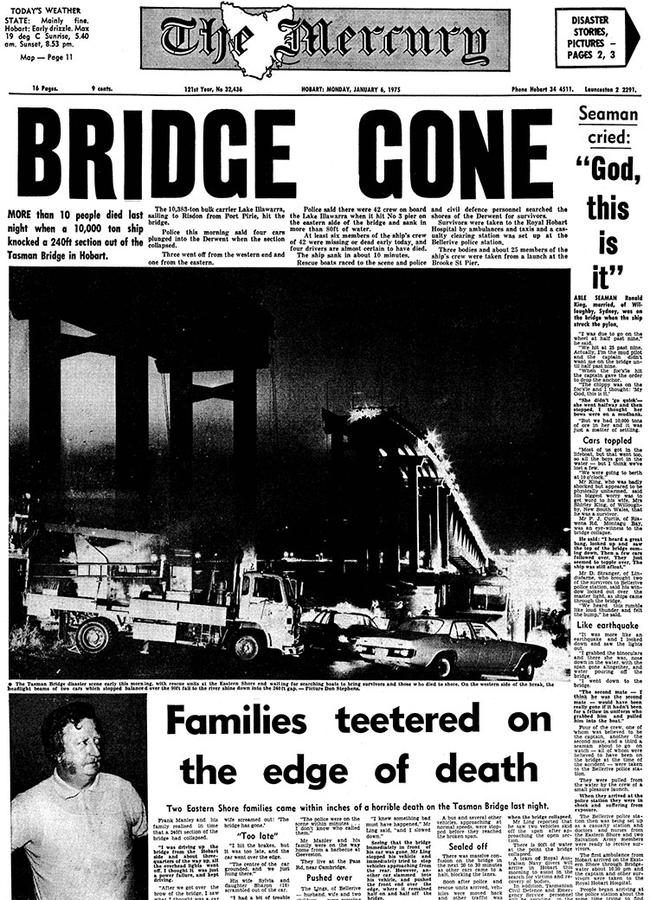

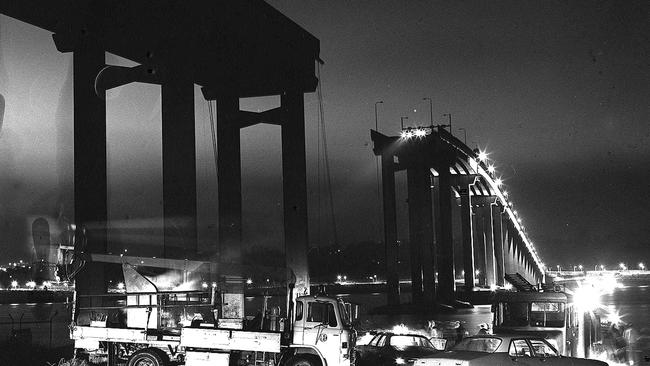

Thousands heard the almighty crunch when the bulk ore carrier Lake Illawarra collided with the Tasman Bridge on the night of Sunday, January 5, 1975.

Some had seen the ship making its way upstream to the zinc works, unusually close to the eastern shore, but few if any would have imagined the scene that was about to unfold.

Attempts to correct the ship’s course had a dire outcome, rendering the vessel uncontrollable as it headed for – and crashed into – pier 19 at the eastern end of the bridge at 9.27pm, bringing down a section of the roadway from high above.

The ship sank in about 10 minutes and still lies at the bottom of the River Derwent, 50 years later. Twelve people lost their lives, including five motorists and seven members of the ship’s crew.

The first responders on the night of the disaster were local residents with their own boats. Thanks to these efforts using a number of small craft, many members of the ship’s crew were rescued from the water.

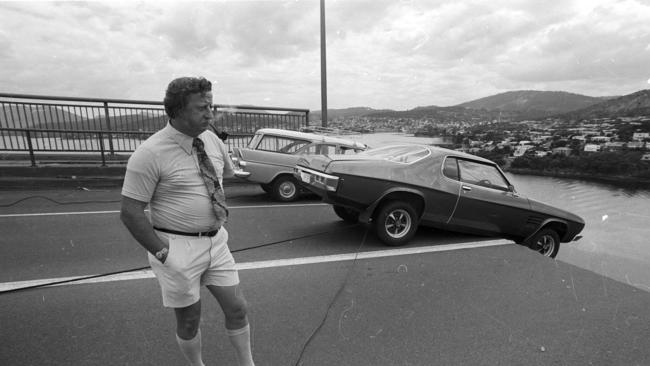

Police and other emergency services were soon on the scene, with much attention focusing on the deck of the bridge where two cars were hanging over the edge.

The stories of the occupants of those vehicles were first told by Mercury reporters Ross Gates and Ross Game, with photos by Barry Winburn and Don Stephens that would become world-famous.

One of the Mercury’s first reports about the disaster was headlined “Families teetered on the edge of death”, and told how they “came within inches of a horrible death” on the bridge.

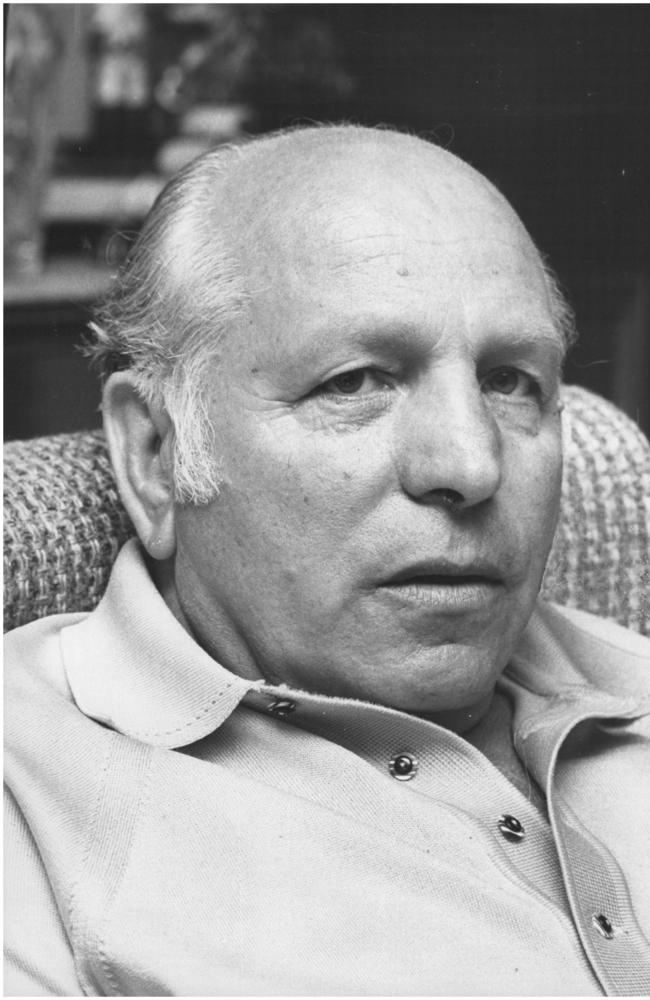

Frank Manley (right) and his family realised in time that a section of the bridge had collapsed, the report said.

“I was driving up the bridge from the Hobart side and about three-quarters of the way up, all the overhead lights went off. I thought it was just a power failure and kept driving,” Mr Manley told Mercury reporter Gates as the pair ran down the bridge to safety with wife Sylvia and 16-year-old daughter Sharon.

“After we got over the brow of the bridge, I saw what I thought was a car broken down on the side of the bridge. I slowed down and then, all of a sudden, my wife screamed out: ‘The bridge has gone.’

“I hit the brakes, but it was too late and the car went over the edge. The centre of the car grounded and we just hung there.”

Murray Ling and his wife Helen and two children were driving over the bridge in the eastbound lanes when the span lights went out.

“I knew something bad must have happened and I slowed down,” he told reporter Game.

Mr Ling stopped when he realised part of the bridge was gone. Another car slammed into his Holden station wagon and pushed the front end over the edge, where it remained half on and half off the bridge.

Mr Ling and his family scrambled from the car and moved to the footpath.

NATIONAL DISASTERS

Coming less than two weeks after Cyclone Tracy had struck Darwin, the bridge disaster stunned Tasmanians and those further afield.

Prime minister Gough Whitlam was overseas and was no doubt in shock when he declared: “It is beyond my imagination how any competent person could steer a ship into the pylons of a bridge … but I have to restrain myself because I expect the person responsible for such an act would find himself before a criminal jury.

“There is no possibility of the government guarding against mad or incompetent captains of ships or pilots of aircraft,” Mr Whitlam said from The Hague.

Protests by the Merchant Service Guild of Australia – and the threat of a nationwide stoppage on Australian ships – led to a full apology from Whitlam the following day. “I unreservedly withdraw any imputation against the captain of the Lake Illawarra and apologise,” the PM said from the Netherlands.

A change in public opinion has not been so quick, with many still believing the ship’s master must have been drunk. Captain Boleslaw Pelc was among 38 members of crew hospitalised after the collision and no trace of alcohol was found in his blood.

A Court of Marine Inquiry would find that Pelc had not handled the ship in a proper and seamanlike manner, and his certificate was suspended for six months.

The Lake Illawarra had been off course as it neared the bridge, partly due to the strong tidal current but also because of inattention by Captain Pelc.

Initially approaching the 10-year-old bridge at eight knots, Pelc slowed the ship to a “safe” speed and attempted to pass through one of the eastern spans rather than the central navigation channel.

Despite several changes of course, the ship proved unmanageable due to having insufficient steerage way. In desperation Pelc ordered “full speed astern” (reverse), at which point all control was lost.

The disaster left many with a fear of using the bridge, and an ongoing temporary closure each time a large vessel passes underneath.

A CAPITAL CITY DIVIDED

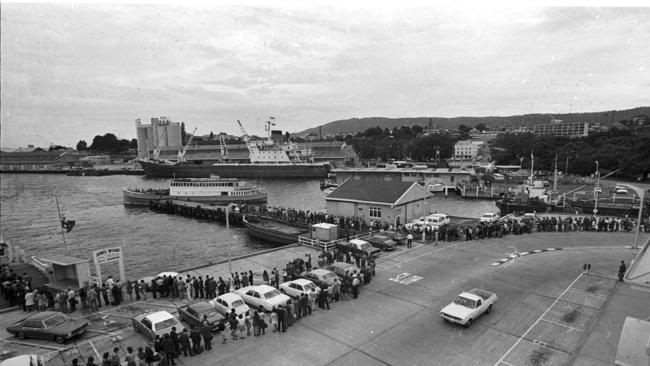

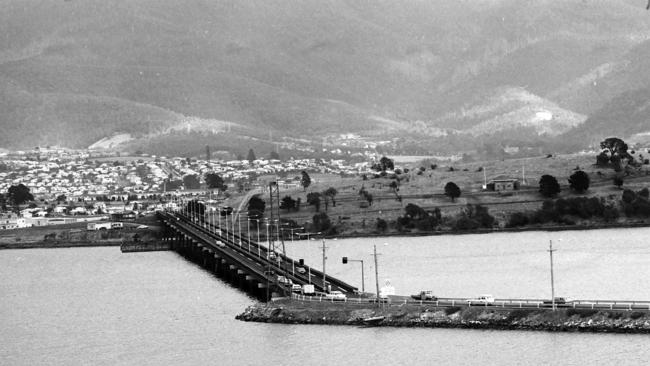

The disaster left Hobart divided. The population of the Eastern Shore’s Clarence municipality had boomed – nearly tenfold – from about 4400 prior to the opening of the two-lane floating arch Hobart Bridge in 1943 to 28,000 when the four-lane Tasman Bridge opened in 1964, and nearly 41,000 in 1974.

Despite the massive increase in population, the district remained largely a dormitory suburb with few local services and a large labour force that had to cross the water every day to workplaces on the western shore.

As the full impact of the disaster hit home, ferry services were massively increased and a hospital ship-style launch was provided to take sick and injured people from the Eastern Shore to the Royal Hobart Hospital.

This sudden revival of river transport was immortalised in a best-selling song titled Ferry Boat Shuffle and popular cartoons by the Mercury’s Kevin Bailey that were eventually published in two compilations titled How to Play Bridge.

SCRAMBLE FOR ALTERNATIVES

The next closest access to the Eastern Shore was a 50km trip via the Bridgewater Bridge, complicated by an unsealed “goat track” through Old Beach.

Two days after the bridge disaster, the Mercury reported that it had been decided that the “suspension-shaking” Old Beach Rd would be rebuilt and sealed.

“Tasmania has been given an almost blank cheque offer by the Commonwealth of help to resolve the problems created by the Tasman Bridge disaster,” the newspaper reported.

“The Premier (Mr Reece) – already faced with liquidity problems which have drained state finances – said yesterday he had ‘very specific’ assurances from the Prime Minister (Mr Whitlam).”

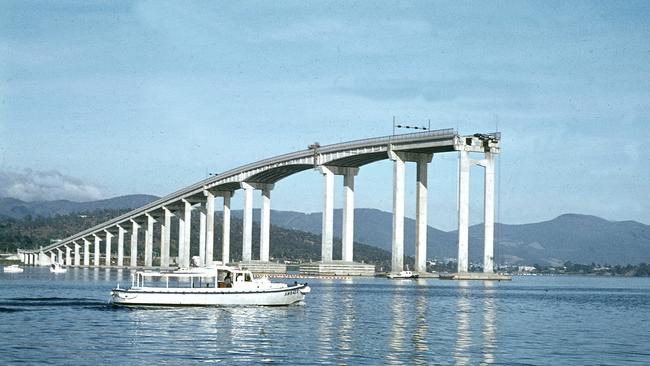

A temporary Bailey bridge was built between Dowsing Point and Risdon by the end of 1975 and there were calls for another permanent crossing, as well as rebuilding the Tasman Bridge.

At 788m, the Bailey bridge was the longest of its kind in the world and it remained in use until the opening of the $49m Bowen Bridge nearby, in 1984.

The temporary bridge was built with “fenders” in place to withstand a glancing blow from the tugboats and lighters used to transport newsprint from the Boyer paper mill to export markets.

The Tasman Bridge reopened in 1977 after a reconstruction program costing about $44m ($291m today), which exceeded the original $14m ($233m) cost of construction.

SALUTE TO BRAVERY

On November 9, 1976, bravery medals were awarded to Lake Illawarra crew members Royse Davies and Graham Kemp (posthumous) for their actions during the disaster.

They, along with police rescue officers, the crews of tugboats and people who lived near the bridge and had rendered assistance, had been praised by the Court of Marine Inquiry chairman Sir John Spicer in handing down his findings in May 1975.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

‘Roads are unsafe’: Councillor struck by car in scary city incident

A Hobart councillor has spoken of a frightening experience where he was struck by a car while jogging in the city recently, as he pushes for further pedestrian safety upgrades across the capital.

Lucky Tasmanian quickly retires after $900k lottery windfall

After learning they had won more than $900,000 on a winning TattsLotto entry over the weekend, a Tasmanian resident has quit their job and is now busily considering new life opportunities.