One of the Northern Territory’s longest-running inquest has wrapped up for the year. Read what the court has heard so far and why the wait for justice will continue.

Territory Coroner Elisabeth Armitage was always going to take months to digest the evidence and deliver her lengthy findings, but the 19-year-old Warlpiri-Luritja man’s family was supposed to have been able to do the same.

Instead, after legal challenges and other delays, what is already one of the Northern Territory’s longest running inquests goes on, now due to resume in February, and for the people of Yuendumu, the three-year wait for justice continues.

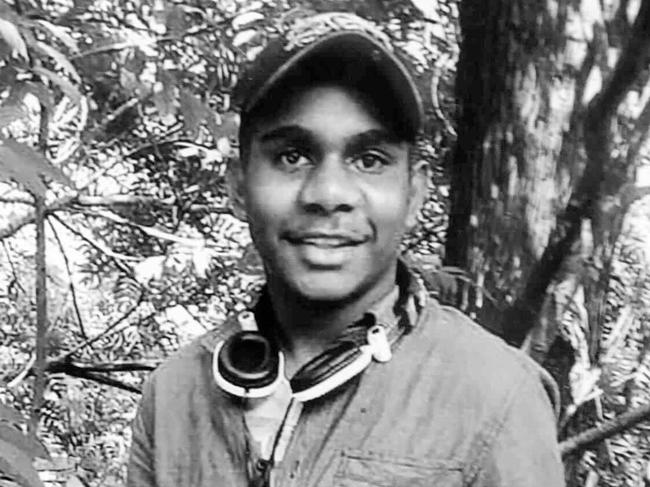

At 19 years of age, Kumanjayi Walker was on the cusp of what, despite his brushes with the law, could have been a long and happy adult life, when officers from NT Police’s Immediate Response Team bailed him up inside house 511 on November 9, 2019.

The litany of mistakes and systemic failures that led them there have now been laid bare for the world to see, along with the blatant racism that ran rampant through the force’s ranks at the time.

But the one man from whom Kumanjayi’s family are most desperately seeking answers, the man they feel owes them answers, the man who killed their beloved relative, is still yet to account for his actions.

Constable Zach Rolfe was acquitted on all charges in the Supreme Court in Darwin in March, more than 1000km away from the small room in Yuendumu where he fired the fatal shots in a poorly planned arrest more than two years earlier.

The not guilty verdict came after Constable Rolfe voluntarily took the stand in his own defence, telling the jury he had acted in self-defence when he shot Kumanjayi three times as he tried to stab Constable Adam Eberl with a small pair of scissors.

From the witness box, Constable Rolfe exuded confidence, appearing eager to tell the world his side of the story, which he would go on to repeat in a series of softball interviews with sympathetic media outlets in the days that followed.

But after evidence emerged that had been ruled inadmissable at the trial — and then some — including text messages downloaded from his phone that included vile, racist slurs against Aboriginal people he was policing, that all changed.

When Constable Rolfe returned to the stand last month, this time in Ms Armitage’s Alice Springs Coroner’s court, he was considerably less forthcoming.

Gone was the man offering extended explanations to Crown prosecutor Philip Strickland SC as he deftly batted away questions about how he “shot Kumanjayi Walker twice in quick succession”.

“Do you want me to explain the difference between a double tap and a controlled pair, for the jury?” he had asked, prompting a curt “No, thank you,” from the thwarted barrister.

This time, a visibly chastened and downcast Constable Rolfe would offer clipped, evasive answers as he grumbled about having been “banned from all police stations” after returning to desk duties from “a government building in Darwin”.

He had joined the army because he “wanted to be a soldier”, he told counsel assisting, Peggy Dwyer, and left because he “wanted to move on”.

“Why?” Dr Dwyer asked: Because he “felt like moving on”.

It was while he was in the army that Constable Rolfe was “taught to show respect, regardless of culture” he said, but only “some aspects” of it, “aspects that should be respected”.

Then after joining the police force in 2016, Constable Rolfe said he completed “Respect, Equity and Diversity” training.

“Do you recall anything about that?” Dr Dwyer asked. “What did that involve?”

Constable Rolfe said it was “pretty self-explanatory”.

“It was teaching us about elements of respect, equity and diversity in the workplace and in the public, I believe,” he said.

“To be honest, the cultural training that we did, I haven’t found the specific use of that in the job, because I’m responding to humans — human problems of humans asking for help and then humans breaking the law.

“I have not been presented with a problem, a cultural problem as a police officer. In saying that, I was in Alice Springs.”

Dr Dwyer: “I appreciate you’re trying to make a point about something, what is it? Do you want to explore that? Do you want to expand on that?”

Constable Rolfe: “No, I’m just saying that, like as a police officer, I’m responding to a job where someone has called for help or someone has broken the law. I have not been called to a cultural issue.”

Constable Rolfe said he was “taught how to respect everyone” and “Aboriginal people are included in that”.

But when Dr Dwyer asked if it had been “obviously racist” when he texted another officer, referring to Aboriginal people as “c**ns” and “grubby f***s”, the trickle slowed to a stop.

“I wish to exercise my right and claim the penalty privilege on the basis my answers might tend to expose me to a penalty,” he replied.

Members of Kumanjayi Walker’s family have spent much of the past three months gathered on the lawns across from the Alice Springs Local Court, or sometimes watching proceedings from the public gallery inside.

Among them has been Samara Fernandez-Brown, Kumanjayi’s cousin, who drew the ire of Zach Rolfe’s legal team last month for calling out his “cowardice” in refusing to answer more questions.

Now, speaking out again from a seat on the grass after the court adjourned for the final time for 2022, Ms Fernandez-Brown says she remains frustrated by the continued delays as the wheels of Western justice turn ever on.

“Every time you think there is an ending, like with this inquest, it’s been extended this year but then also next year and then we’ve still got to wait the six months for the report, and then wait to see if those things are implemented,” she says.

“So in a sense it really feels like it’s never ending, but I think at the same time you’ve got to acknowledge and appreciate that that is required, and really important if we do want some changes that are going to come out, to make sure that this doesn’t happen again.

“It feels overwhelming but at the same time really surreal — really surreal — but there is a sense of relief for a lot of information that has come out, and feeling somewhat heard, you know, community and family are actually feeling a bit more heard this time around, which is a positive aspect for sure.”

With Constable Rolfe now due to resume his evidence in February, pending a legal challenge to a Coroner’s ruling compelling him to do so, along with NT Police deputy commissioner Murray Smalpage, Ms Fernandez-Brown says she is still hopeful that some form of justice will be done.

“I think there just needs to be a level of accountability held for him and his actions, and for me that would look like him being fired by the police force,” she says.

“I think that would show an acknowledgment for Warlpiri and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, but also just to acknowledge that racism isn’t accepted.”

For that to happen, Ms Fernandez-Brown says there needs to be “clear systemic changes within the police force” and an acceptance that systemic racism “does exist”.

“There needs to be that acknowledgment and then further steps to ensure that that racism and violent behaviour isn’t accepted, and that people don’t need to accept that behaviour by the police, and that there are going to be consequences for this behaviour, because up to this point there hasn’t been and so why would they change?”

The NT News was one of only two media outlets to report on every day of the inquest from inside the courtroom and was among those invited to Yuendumu when the court travelled there in November.

But some other journalists were specifically excluded from that invitation after what many in Yuendumu saw as one-sided reporting that glorified the acquitted police officer while condemning a teenager who was no longer around to defend himself.

With several weeks of hearings still to come, Ms Fernandez-Brown says one of the major lessons to be learned from what has emerged so far is for there to be more sensitive reporting on issues affecting Aboriginal people by outsiders.

“In the murder trial, Kumanjayi was really vilified and Rolfe was painted as a hero and the media really pushed that narrative, well at least a lot of outlets did, there were a small number that we trusted and that weren’t pushing that narrative but the bulk of media were,” she says.

“It’s now come out in the inquest that that’s not the truth and that’s not the reality and it was very dangerous to be pushing that narrative.

“So I think the ability to critically think about situations and to have that empathetic lens for the bigger picture and, again, in Australia that’s that historical picture to how Kumanjayi got to where he is as an individual.”

In the meantime, Ms Fernandez-Brown says Kumanjayi’s family will continue to mourn for a young man who was “loved so deeply by his community” and loved them deeply in return.

“I think as a society it’s so easy to hold yourself at arms length from somebody because you don’t want that to be your reality,” she says.

“But I think it’s really important to sit in our shoes and to think about how deeply he is missed and how much of an impact he’s had on our community, and to really humanise him, and to remember that this was a 19-year-old man whose life was taken away from him.”

The inquest will resume in Alice Springs on February 27 while Justice Judith Kelly is expected to hand down her ruling on whether to uphold the Coroner’s order compelling Zach Rolfe to testify next week.

‘It’s a coup’: ‘Terminated’ Alice Springs principal’s explosive allegations

The former principal of troubled Alice Springs school is alleging he was sacked after standing his ground over a proposal which is going to be ‘a sh-t show’.

Gaps in Darwin maternity services highlighted through stories of loss

Darwin families are making plans to leave the NT as shocking testimonies reveal gaps in maternity care, with some mothers seeking help four times before tragedy struck.