WHEN Zach Rolfe walked into Courtroom 2 in the Supreme Court in Darwin each day during the five weeks of his trial for the alleged murder of 19-year-old Kumanjayi Walker, he was all but forced to stride across the Milky Way Dreaming mosaic that takes pride of place on the building’s floor.

Three decades before the young lives of Constable Rolfe and Mr Walker collided violently on that fateful evening in 2019, Warlpiri artist Norah Napaljarri Nelson, had sat down in the same red dirt in the Central Australian community of Yuendumu where the teenager died, to complete the painting that would be the mural’s inspiration.

At around the midway point in the trial, just on the other side of the Milky Way Dreaming, Chief Justice Michael Grant presided over a ceremonial sitting of the court, marking the 30th anniversary of the mosaic’s unveiling at the opening of the new Supreme Court building in 1991.

In her speech marking the occasion, Attorney-General, Selena Uibo, noted that the installation created “a link between this building and beautiful Central Australia”.

“The work depicts the Dreamtime legend of the seven Napaljarri sisters who turned to fire and placed themselves as stars in the night sky in order to avoid pursuit,” she said.

“Their pursuer, a Jakamara man, also turned himself into a star but by reason of ending up in the morning sky was unable to complete his pursuit.”

Meanwhile, across the way, another less auspicious link between the institutions of colonial Australia and the ancient people of Yuendumu was being forged, the ripples from which are also set to echo through the decades.

AS February ticked over into March and the trial entered its fourth week, the Crown called its final witness, Detective Senior Sergeant Andrew Barram of NT Police’s Professional Standards Command.

Sergeant Barram’s testimony in front of the jury was among the most damning – including that it was neither “reasonable” nor “necessary” for Constable Rolfe to have fired the fatal shots – as well as the most controversial.

For his trouble, and as a reflection of his key role in the prosecution, Sergeant Barram would end up being one of the focal points of defence barrister, David Edwardson QC’s closing address.

The real villain of the piece was the NT Police “executive”, who had collectively “thrown everything at Zachary Rolfe because of a decision that should never have been made”, Mr Edwardson said.

But Sergeant Barram was its unflinching, human face, “deployed to justify these charges”.

The “flawed prosecution” was, Mr Edwardson said, “all about the executive of the Northern Territory Police force attempting to justify what was the unjustifiable”, parroting Crown prosecutor Philip Strickland SC’s words from a day earlier.

“As of Wednesday last week, when the Crown closed their case, they had 841-plus days since the decision was made to charge Zachary Rolfe, to actually produce a case,” he said.

“The Crown produced 40 witnesses to support the narrative that Rolfe, a police officer, is guilty of murder – we say, they have not come close.

“In fact, with the exception of Senior Sergeant Barram, each police witness only confirmed the truth of the matter – what Zachary Rolfe did was, not only what he was trained to do, but his response by firing all three shots was reasonable and proportionate in the circumstances.”

Mr Edwardson said the man he had dubbed an “armchair, so-called expert” was “undoubtedly, the most controversial witness” in the trial and “the cornerstone of the prosecution case” that Constable Rolfe was unjustified in shooting Mr Walker three times as he wrestled with his partner, Adam Eberl.

“He expresses his opinion, after having the benefit of pushing the pause button, to try and identify in 2.6 seconds, whether there had been such a change of circumstance that there was non-compliant training and an unjustifiable response,” he said.

“We say, that Senior Sergeant Barram is neither credible, nor reliable, he is simply a mouthpiece for the executive and has, no doubt, been wheeled in here in justification for this investigation, which took place after Zachary Rolfe had been arrested, you might think, in dubious circumstances, where no proper investigation, or meaningful investigation, had occurred.”

Mr Edwardson said unlike Sergeant Barram, Constable Rolfe “did not have the luxury” of assessing tactical options, “frame by frame”.

“He had been stabbed, his partner was locked in mortal combat with an armed assailant with a predisposition for violence,” he said.

“Zachary Rolfe, as we’ve said, could not push the pause button, he had to make a split-second, intuitive decision, based on his training, and ladies and gentlemen, it required, we suggest, only one course of action.

“Tragically, he had no choice – he had to pull the trigger, or risk the real possibility, that Constable Eberl would or could be, fatally stabbed.”

Then Mr Edwardson asked this pointed question: “Who would you rather have watching your back in this volatile exchange? Constable Zachary Rolfe, or the armchair expert, Senior Sergeant Barram?”

In his closing address, Mr Strickland said Sergeant Barram had reached his opinions based on watching the body-worn footage, both in slow motion and in real time.

“His critical opinion is included in his report that is now before you, is based upon the real time video and his opinion, (is that) the second and third shots were neither reasonable nor necessary,” he said.

“And that is because that things had changed substantially from when the first shot was fired.”

But it wasn’t just Constable Rolfe who was a victim of the bogey man of the top brass, officer in charge at Yuendumu, Sergeant Julie Frost, had also been “thrown under the bus by the executive”.

While Sergeant Frost’s testimony that she had told Constable Rolfe’s Immediate Response Team they were to arrest Mr Walker at 5.30am was unhelpful to his case, she too was “a victim of this appalling investigation”.

Mr Edwardson said an incident in which Mr Walker was seen rushing at police armed with an axe three days before his death would have been “terrifying for her”, and doubly so given one of those officers was her partner, Christopher Hand.

“She recognised the potential for a conflict of interest, but in truth, she probably should never have been put in the position of being officer-in-charge of the members of the IRT team, and the dog handler, when they were deployed on 9 November 2019,” he said.

In his closing submission, Mr Strickland said Sergeant Frost knew her partner was involved in the axe incident and regarded it to be “very, very, serious”.

“But from the get-go, she was intent on trying to achieve a peaceful resolution to the situation,” he said.

“She tried her best to get Kumanjayi Walker to surrender himself without the use or necessity of force.”

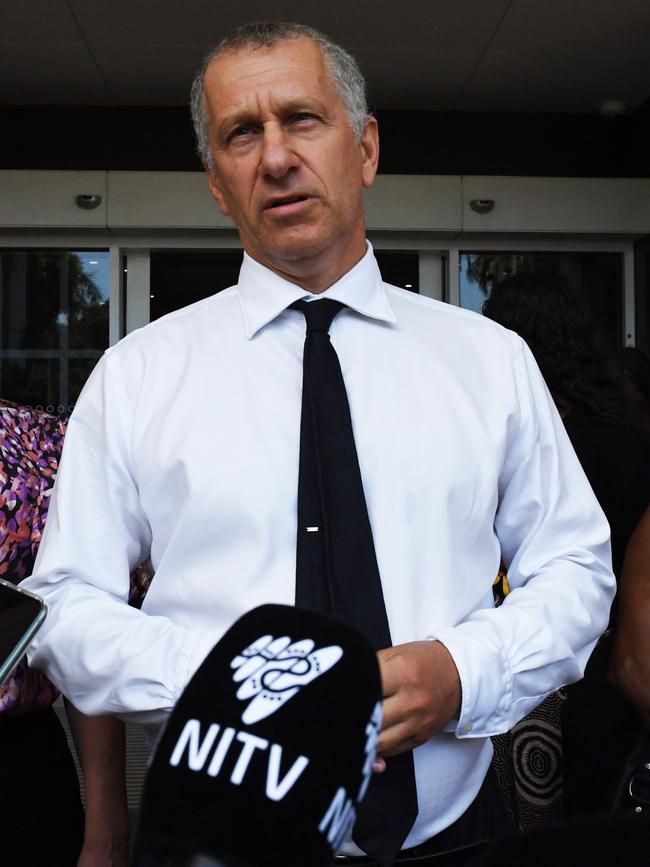

The closest Mr Edwardson got to going toe to toe with his bête noire during the course of the trial, was when Assistant Commissioner Travis Wurst took the stand on February 17, and he didn’t hold back.

Mr Wurst, he said was right at “the top of the chain of command in this case” and “it must be said that he had absolutely no idea what he was doing or what was involved”.

“After all, he has told you that he didn’t even know what the IRT were capable of doing, he didn’t know what IRT stood for, and what capacity they had at the time of their deployment on 9 November 2019,” he said.

“What does that tell you about the executive?”

In his evidence, Mr Wurst said the deployment he approved “wasn’t necessarily the IRT as it was understood”.

“It was the members within, to provide additional support,” he said.

“So the IRT, as I understood it, was just a collection of frontline officers from within Alice Springs.

“And the explanation provided to myself was that the people attached to that unit or were linked to that unit, whenever there was a requirement for extra duty, they were responsive.”

IN THE end, the prosecution itself may have helped seal Zach Rolfe’s fate.

In taking the stand to give jurors his side of the story on March 2, Constable Rolfe had exposed himself to cross examination by Mr Strickland, a significant risk for any defendant.

But it also gave him a chance to tell jurors his side of the story, what he said he saw, what cannot be seen on the body-worn camera footage from the day in question.

“I could see Kumanjayi’s right arm, with the blade in it, still moving and stabbing Constable Eberl on the ground … I was still in fear for Eberl’s life,” he said.

“I then fired two more rounds into Kumanjayi’s centre of mass, at which point, I observed his right arm stopped trying to stab my partner, at which time I holstered my Glock.”

It was that account, Mr Strickland would later tell jurors in his closing address, that could be the key to the whole case.

If they believed Constable Rolfe was telling the truth, he said, they “must find him not guilty”.

AFTER finalising his summing up of the evidence for the jury on Thursday, Justice John Burns invited the parties to suggest anything he might have left out and Mr Edwardson did not hesitate to revive Mr Strickland’s “extraordinary – but perfectly proper – concession”.

“Ladies and gentlemen, let me make this clear, if you believe as a reasonable possibility that that evidence is true, you must find him not guilty of all three counts, no question about that,” Mr Strickland had said, he reminded the court.

“I don’t think, with respect, your honour specifically directed the jury at all in those terms and it seems to me, with respect, it’s such an absolutely critical and proper concession made by my learned friend that – and it’s a complete answer to all three charges – that the jury must be directed, and reminded specifically of the concession that was made by my learned friend in express terms,” Mr Edwardson said.

Justice Burns agreed.

JURY verdicts are by their nature, inscrutable.

Jurors do not have to explain how they reached their decisions or give reasons for them and, unlike in the United States, their identities are protected by law from nosy journalists.

But the fact remains, despite all the complex legal issues raised in the case, some of which made it all the way to Australia’s highest court in Canberra, it may have ultimately boiled down to just one question.

Did they believe beyond a reasonable doubt that Zach Rolfe was lying when he told them he could see Mr Walker stabbing his partner and that as a result, he feared for his life, when he shot him three times in house 511 on November 9, 2019?

As per Justice Burns’ directions, that was the first question they needed to ask themselves, and if they found the answer was no, the trial was over.

WHEN Warlpiri elder, Paddy Japaljarri Sims, was asked if it would be disrespectful for people to walk on the Milky Way Dreaming mosaic on the floor of Darwin’s Supreme Court building, he is said to have replied that it would be alright “as long as people don’t wear muddy boots”.

By the time Zach Rolfe’s path crossed with that of the Seven Sisters in February 2022, he had long since traded his red dirt stained police issue boots for a spotless pair of elastic sides, so there was no danger of disrespecting the artwork.

After the jury handed down its verdict of acquittal on Friday, now too, in the eyes of the law, his hands are clean.

In commemorating the mosaic’s 30th anniversary during week two of the trial, former Attorney-General, Daryl Manzie, remarked that it was self-evident that “all communities must have a justice system that resolves conflict and passes judgement”.

“Because without such a system we’d live in anarchy, the strong would overwhelm the weak and it certainly wouldn’t be a very safe and comfortable existence,” he said.

While justice has now officially been done, it will likely be some time before the friends and family of the slain Kumanjayi Walker will be able to return to anything approaching a comfortable existence.

JUST to the right of the Milky Way Dreaming mural, sit the Larrakitj mortuary poles that were gifted to the court by the Territory’s Yolngu people in a Wukidi ceremony in 2003, commemorating another fateful clash between a Territory cop and the NT’s original inhabitants.

The poles serve as permanent memorial to Dhakiyarr Wirrpanda, who faced trial in Darwin for the spearing death of Constable Albert McColl in 1931, and was convicted and sentenced to death by hanging.

Dhakiyarr’s conviction was later overturned by the High Court but on the night he was released from Fannie Bay Gaol, he vanished without a trace.

The aim of the Wukidi ceremony was to finally lay Dhakiyarr’s spirit to rest in what then Solicitor-General Tom Pauling QC described as “undoubtedly the most powerful act of reconciliation in Australia, ever”.

Members of Constable McColl’s family also attended the ceremony, some of whom afterwards travelled to Arnhem Land to stay with their Yolngu hosts.

Now, almost two decades later, any such reconciliation between the families and communities of the two men whose stories became inextricably entwined in a small room in Yuendumu on November 9, 2019 still feels a long way off.

NT man ‘must be punished’ for sick act against niece

The offender watched on as another man raped his niece. After witnessing the horrific act, the man made a shocking decision. Warning: Disturbing.

Fatal hit and run delivery driver sentenced

A Darwin delivery driver was sentenced for running over three people sleeping on the street — one of whom later died from their injuries — before fleeing the scene. Read the details.