William Tyrrell’s foster parents reveal grilling by Gary Jubelin

William Tyrrell’s foster parents have revealed how former detective Gary Jubelin interrogated them for three hours. It comes as Jubelin, who has been convicted of illegally recording conversations, defended his handling of the case.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Three years after her son disappeared from a quiet country street, William Tyrrell’s foster mother was asked to meet the lead detective at a police station.

She’d known Detective Chief Inspector Gary Jubelin since he took carriage of the case in early 2015.

She knew he had spent time assessing her and listening carefully to their discussions for any hint she knew more than she was letting on.

They had developed a mutual trust.

“He knows us inside out,” she says now.

But when Jubelin met them at Parramatta Police Station in 2017, he wasn’t smiling.

“You’re not going to like me after this,” Jubelin told the foster parents.

“I’m going to ask you questions that make you feel uncomfortable.”

The husband and wife were taken to different interview rooms. They were treated like suspects.

MORE FROM AVA BENNY-MORRISON:

More cops to crack down on COVID-19 quarantine

Richard Buttrose back dealing ‘bags of white stuff’

Jubelin asked William’s foster mother if she played a hand in the toddler’s disappearance. He asked if William’s foster grandmother was hiding anything.

“I was livid and really furious with Gary because of the trust,” William’s foster mother, who can’t be legally identified, says now.

“I remembered very distinctly being really affronted that he would ask the questions he asked and some of the scenarios he put to me,” she says.

“I looked at him in amazement. I was gobsmacked. I was indignant and taken aback that someone would even consider the scenarios he put forward.”

“We trust him implicitly and we knew we had been 100 per cent upfront with everything.

“If we had known we had to go there to be interviewed independently and we can’t talk to each other about it, we wouldn’t have.

“The last thing we want to do is say something that gets in the way of finding out what happened.”

Jubelin believed the foster parents had nothing to do with William’s disappearance from Kendall on the Mid North Coast in 2014 – one of the state’s most enduring mysteries.

But at the urging of other detectives, he personally took on the task of conducting a tough interview with the foster parents to categorically rule them out.

She walked out of the police station furious, unaware police had bugged their car to listen to their reactions afterwards.

All they got were a few disparaging remarks about Jubelin being an “arsehole”.

“He interviewed me as if I was a suspect,” she said.

“So if he is treating me like that he was to be treating other potential suspects in an even more focused way.

“That showed me he was all over this investigation and he wasn’t half hearted, he was fully invested.

“If someone is fully invested in looking for my child then I support them.”

In an extraordinary turn of events, on Wednesday William’s foster mother entered the witness box to give evidence of her belief that Jubelin is of good character.

The ex-police officer of 34 years, who led some of the country’s most high profile murder investigations, became a convicted criminal after Magistrate Ross Hudson found him

guilty of illegally recording four conversations with Paul Savage, a one-time suspect in the William Tyrrell investigation.

The magistrate labelled his evidence “unbelievable and untenable” and criticised Jubelin’s treatment of Mr Savage, a 75-year-old pensioner, in and out of the interview room.

For Jubelin, the conviction stings much less than Mr Hudson’s words from the bench: not just that his evidence was not believable, but that he had pursued Mr Savage despite “no DNA, no fingerprints”. Mr Hudson also dismissed as “spurious” Jubelin’s theories that Mr Savage or his wife, now deceased, might possibly have hit William accidentally with a car, or that William might have run into their backyard and drowned in the pool and then panicked and disposed of his body. Mr Savage has not been charged with any offence.

The character witnesses called by Jubelin’s legal team included former senior crown prosecutor Mark Tedeschi, Greens MP David Shoebridge and former police deputy commissioner Nick Kaldas, one of the state’s most decorated officers.

“I spent a career locking criminals up and now I am one,” Jubelin says grimly. It’s the reputational damage — and the Magistrate’s criticism of his homicide skill — that weighs most heavily.

Jubelin, who has lodged an appeal against the conviction and $10,000 fine, says in hindsight he wouldn’t have recorded the conversations with Mr Savage. But he struggles to find anything he would have done differently.

“I know people want me to be humble and contrite but it is hard when I believe in what I am doing,” he says.

“I could have been someone everyone liked, but I would have had to compromise my beliefs in what we should be doing in investigating a homicide,” he says.

“Maybe I should have stood up even harder and that is not what people want to hear.

“I could have taken an easier path and compromised my beliefs and values.

“But that is a price I wasn’t prepared to pay and I’m suffering the consequences.”

It is this conviction — often seen as arrogance — that has made Jubelin an enigma to the public and a royal pain to the police hierarchy.

Since graduating from the academy on April 24, 1985, he’s been shadowed by the phrase: “like a dog with a bone”.

The first homicide he ever worked on, “a man by the name of Kelly, found deceased in his home at Hornsby,” took 10 years to solve.

The victim had a pre-existing heart condition and the post mortem ruled he died from a heart attack.

It was put on the cold case pile for a decade until Jubelin looked at the case again and ended up charging two people with disposing of a body.

It wasn’t a murder charge but it was a small form of justice.

First Class Constable Jubelin’s refusal to let an unsolved case pass by would become synonymous with his policing style.

“He is pretty dogmatic in his approach,” Angelo Memmolo, a former homicide detective who retired from the police force last year, says.

“Where he puts people off is if he thinks this is the way to go then there is very little compromise in him.

“I mean that in the nicest way possible. The way he approaches things is: ‘I’m not compromising on victims.’ Sometimes that puts him at loggerheads with the bosses.”

Former Deputy Commissioner Nick Kaldas, who also gave character evidence for Jubelin, says Jubelin was often the first one in the office and the least one out.

“And you have to remember Inspectors don’t get paid overtime,” Kaldas says.

“You basically work because you care and he is one of the hardest workers I have ever seen in the NSW Police Force.”

Some of the investigations Jubelin has worked on have drawn out over decades; the murder of drug dealer Terry Falconer, the unsolved killings of three children in Bowraville in the 90s and the disappearance of Matthew Leveson.

With homicide victim families, he has unashamedly used the media, parliamentary inquiries and navigated legal minefields to get answers, even if that doesn’t mean an arrest.

Jubelin has his supporters but there are also detractors.

They point to his ego, inability to take no for an answer and public profile.

Mr Memmolo, who has known Jubelin since the 90s when they worked at the armed holdup squad together before moving into homicide investigation, suspects there was some jealousy around Jubelin’s media profile.

“He always uses his media presence for the betterment of victims well,” he said.

“He was able to push the Bowraville job because of the presence in the media. But some people didn’t like that because it was bigger than their own profile.”

From a management point of view, Jubelin can be difficult to rein in if he sees something worth pursuing.

The 57-year-old cut his teeth as a detective in major crime in the North West Region, from the “stick ups” to drug investigation.

He said he worked with great detectives who became mentors and many still support him today.

Several colleagues in the armed hold-up squad were disgraced at the Wood Royal Commission in the 1990s for under-the-table deals and outright corruption.

How did Jubelin, then a junior cop surrounded by some older, crooked and intimidating officers, keep his nose clean?

A combination of rat cunning and fitness, he says.

“If you want to come over the top of me then you better be prepared to fight,” he said.

“I think in that regard I was given some space. I was respected because I did lock up the bad guys.

“Even if they didn’t like me or I didn’t fit the mould they wanted, they respected me because I locked up bad guys.

“When it is all said and done, that is what it is all about.”

That is the tough-talking, defiant, furrowed-brow cop speaking.

But there’s also the yoga-practising, green tea drinking spiritual father-of-two (and grandfather of adored toddler Zion) whose idea of a holiday involves silent meditation in the Himalayas.

The families of homicide victims he forges close bonds with see both sides.

In 2015, 22-year-old Courtney Topic was shot dead by police outside a service station in southwest Sydney.

She was suffering a severe episode of psychosis and holding a knife in one hand and a soft drink in the other.

Having never dealt with police before, the Topic family didn’t know what to expect or how often they’d be updated on the investigation into their daughter’s death.

But after five months passed with no contact from police, Courtney’s grandfather marched in Cabramatta Police Station and demanded an explanation.

That afternoon, Jubelin, whose team was investigating the police’s actions in the shooting as a “critical incident”, turned up on the doorstep.

“He came in and sat at our table and we were still in shock and had no idea what was going on,” Courtney’s mother, Leesa Topic, says.

“Gary was up straight and honest. It allowed us to have faith in him, not in the police but in him.

“He took our wrath on a number of occasions when it got too much and we didn’t know what we were dealing with. But he took it on and explained everything for us.”

At the time, Jubelin had just taken over the Tyrrell investigation.

Child abductions, the kind where a three-year-old is snatched from his grandmother’s yard in broad daylight, are seldom heard of in Australia.

Stranger abductions are even rarer.

“I can say hand on heart it is one of the hardest investigations I have ever done,” Jubelin says.

It would also be his last.

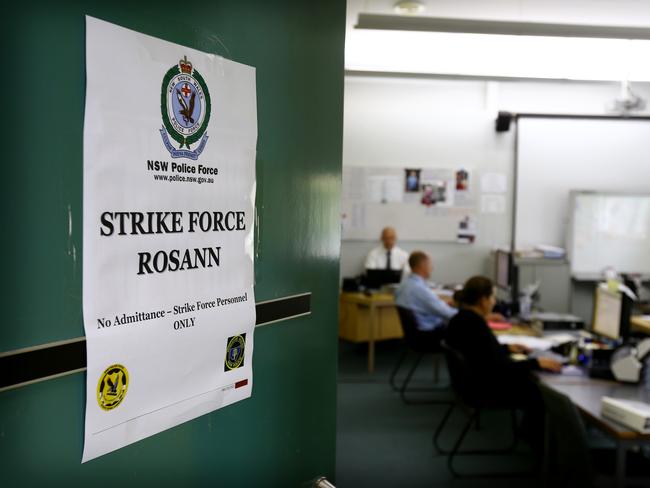

Cracks started to show in Strike Force Rosann, the team of detectives tasked with investigating William’s disappearance, in late 2017.

Resources were no match for the job’s enormity and detectives disagreed on leads and persons of interest, including Kendall local Paul Savage.

Differing views are healthy on any investigation but some members of Jubelin’s team began to question his judgment.

The discontent in the ranks culminated in an almighty argument between Jubelin and his second in charge, Detective Sergeant Craig Lambert in mid-2018.

When Lambert joined the team in 2016, Jubelin admired his kickboxing credentials — six times Australian champion — and his motivation.

Before they almost came to blows in the halls of the Homicide Squad office, Lambert, who is now on long term leave, had worked Jubelin’s corner at a police charity boxing fight.

“I don’t begrudge him — I think the pressure of that job got too much for him,” Jubelin said.

But the confrontation rolled into further dissent.

After being removed from the investigation in January, 2019, Professional Standards Command (PSC) detectives investigated a suite of allegations made against Jubelin.

Internally, complaints of bullying were sustained.

Jubelin denies bullying any staff and refers to evidence from his former boss, Mr Kaldas, that he got on “famously with his workmates”.

An officer on the strike force, Detective Senior Constable Greg Gallyot, had also made a statement that Jubelin directed him to illegally record a phone call in December, 2017.

PSC seized Jubelin’s phone and found three recordings of conversations between him and Paul Savage.

Last year, the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions ruled there was enough evidence to charge the officer.

But the final decision came down to senior police, including an Assistant Commissioner and Deputy Commissioner.

They mulled over it for at least a week before two PSC detectives knocked on Jubelin’s front door and handed him a court attendance notice for four breaches of the SDA.

Opinion is divided within the police force as to whether the decision to charge Jubelin was a good one given the very public fallout.

On one hand, there was evidence he had done the wrong thing — and police couldn’t treat him as “above the law”.

But Jubelin was never going to go down quietly — so the charges would inevitably result in an unpleasant public ordeal.

In Jubelin’s mind, police needed to justify their internal investigation.

“I was ostracised, humiliated and isolated,” he says.

“What has happened to me has changed me. I am no longer with the organisation I gave my life to and my mistrust of people has increased.

“I feel the pressure of all the people that have supported me. I feel I have betrayed them.”

Jubelin is sticking to the belief that he recorded the conversations to protect his lawful interest and sticks by his investigation.

“The way I led the William Tyrrell investigation, I won’t concede I have done anything wrong there,” he said.

“With Paul Savage, I won’t concede a millimetre.”

Jubelin has lodged an appeal against his conviction and $10,000 fine.

Originally published as William Tyrrell’s foster parents reveal grilling by Gary Jubelin