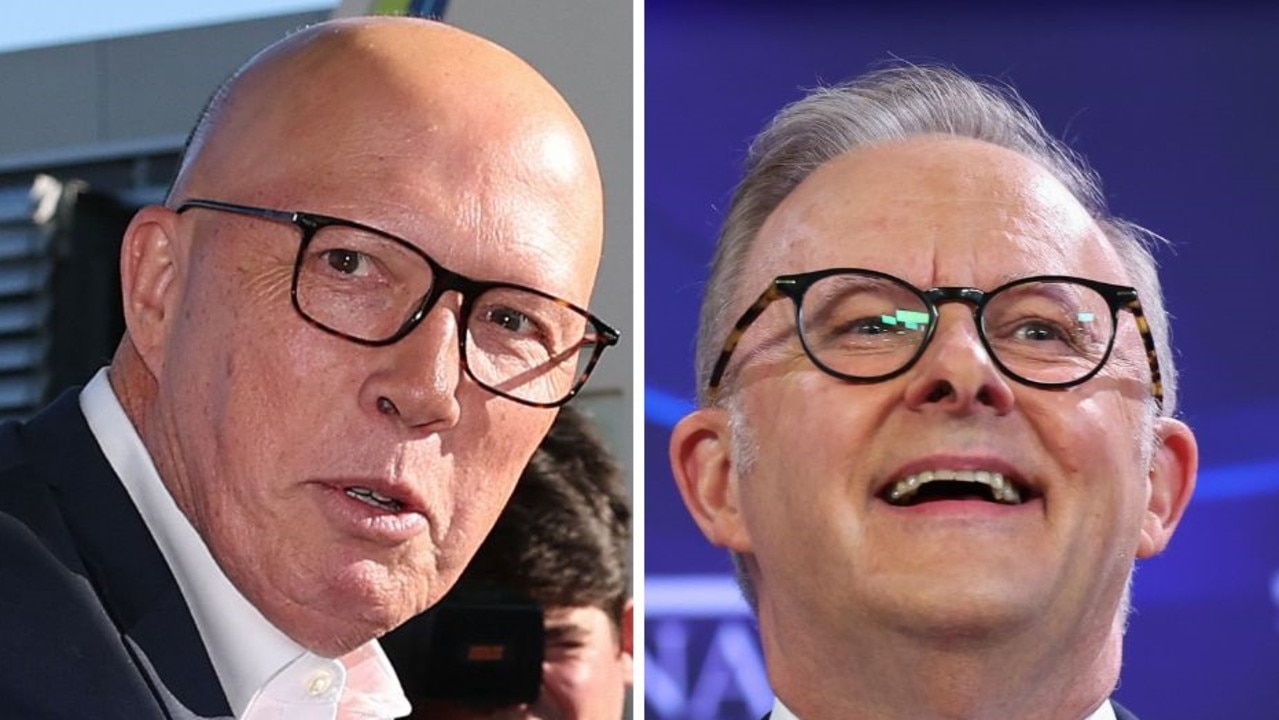

‘Struggles, triumphs’: Key moments of Indigenous Australians’ history

Indigenous Australians have a rich history, one which Aboriginal elder Uncle Peter Williams is proud to share with the next generation. See the key history moments.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

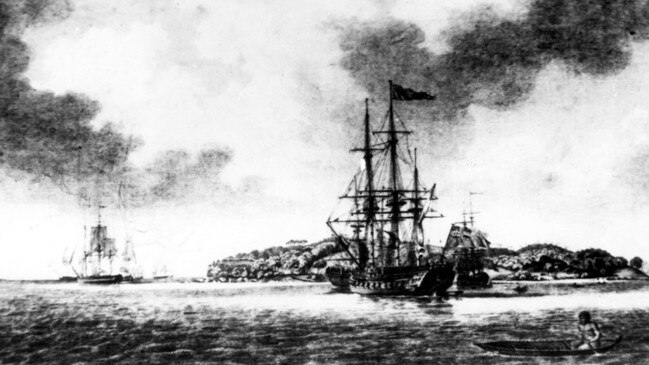

As we edge closer to the Voice referendum, we take a look at some of the key struggles and triumphs of our nation’s first peoples — one of the oldest living cultures in the world — following Captain Cook’s arrival in the now Kamay Botany Bay National Park on April 29, 1770.

FIRST FLEET’S ARRIVAL

British settlement of Australia started in January 1788, when the First Fleet arrived in Sydney Cove. Having been isolated from the world for thousands of years, Aboriginal people had no resistance to viruses such as smallpox, syphilis or influenza.

MASSACRES

According to University of Newcastle research, massacres of Indigenous people (more than six people at one time) spread from southern Australia from 1794 to 1860, with peaks in the 1820s in Tasmania, and the 1840s in New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia. From the 1860s to 1870s the killing spread north into Queensland, then from 1880s to 1930 smoved to the Northern Territory and northern WA.

STOLEN GENERATIONS

The Stolen Generations refer to the thousands of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children who were forcibly removed from their families and placed into institutional care or with non-Indigenous foster families, as a result of laws or policies. The 1997 Bringing Them Home report, based on the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission’s Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from their Families, found between one in 10 and three in 10 children were forcibly removed between 1910 and 1970.

INDIGENOUS RIGHT TO VOTE

Prior to 1962, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were not given the right to vote in federal elections.

The Commonwealth Electoral Act 1962 granted all Indigenous Australians the option to enrol and vote in federal elections – but it was not compulsory, as it was for other Australians.

The states followed and compulsory enrolment for Indigenous Australians was eventually enacted in 1983.

Under the Victorian, New South Wales and South Australian constitutions, Aboriginal men over 21 had the right to vote in the 1850s. Tasmania followed a few decades later in 1896, but laws denying them the vote were enacted in Queensland in 1885, WA in 1893 and NT in 1922.

INDIGENOUS REFERENDUM 1967

On May 27, 1967, almost 91 per cent of Australians voted Yes to change the Constitution so Aboriginal people would be counted as part of the population and to acknowledge them as equal citizens, and granted the federal government power to make laws on their behalf.

As a result, Section 127 of the Constitution was deleted and Section 51 (xxvi) was amended.

BEING COUNTED IN THE CENSUS

The 1967 Referendum paved the way for Aboriginal people to be counted as part of the nation’s population.

The Census had been running for some time but the 1971 count included Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as citizens of the country.

The question relating to race allowed people to choose which they identified with most. About 116,000 Australians identified themselves as having Aboriginal (106,000) or Torres Strait Islander (10,000) origin, which was 30,000 more than those who identified themselves as being greater than 50 per cent Indigenous in the 1966 Census.

There was a further increase to 160,000 Indigenous Australians in the 1976 Census.

MABO DECISION

In 1992, the High Court of Australia recognised native title in the Mabo legal case. The decision was a step forward in recognising land rights of Indigenous Australians.

When Captain James Cook claimed ownership of Australia on behalf of Great Britain, it was done on the basis of terras nullius, or “nobody’s land”, according to British law – meaning Australian Aboriginal people had no claim to the land on which they had lived for tens of thousands of years.

In 1835, John Batman used a treaty to buy land around Port Phillip Bay, now Melbourne, from local Aboriginal people. Later that year, NSW Governor Richard Bourke made a proclamation aimed at preventing people dwelling on land without government approval and if so, they would be considered trespassers.

In May 1982, a group of Merian people from the Eastern Torres Strait, led by Eddie Koiki Mabo, lodged a case with the High Court for legal ownership of the island. Over 10 years, evidence presented showed eight clans of the Mer (Murray Island) people had occupied on the island for hundreds of years.

On June 3, 1992, six of the seven judges agreed Meriam were the traditional owners of the lands of Mer.

PAUL KEATING’S REDFERN SPEECH

Then-prime minister Paul Keating delivered an impassioned speech on December 10, 1992 on the eve of the International Year of the World’s Indigenous people. “Isn’t it reasonable to say that if we can build a prosperous and remarkably harmonious multicultural society in Australia, surely we can find just solutions to the problems which beset the first Australians, the people to whom the most injustice has been done,” he said.

“ … We took the traditional lands and smashed the traditional way of life. We brought the diseases. The alcohol. We committed the murders. We took the children from their mothers. We practised discrimination and exclusion. It was our ignorance and our prejudice. And our failure to imagine these things being done to us,” he said.

NATIVE TITLE ACT

The Mabo High Court ruling led to the passing of the Native Title Act 1993, which provided the framework for Indigenous Australians to make native title claims.

The Native Title Tribunal was established and the Act gave the Federal Court jurisdiction to manage Native Title application and future access of land claimers.

To succeed, Indigenous people had to prove continuous connection to that land, which was challenging given many were forced from their lands.

Native Title gives the right to share the land with other parties with an interest in the land. It does give the applicant exclusive rights to the land, and can be superseded by the rights of private owners or leaseholders.

NATIONAL APOLOGY

On February 13, 2008, then-prime minister Kevin Rudd delivered a formal apology speech in parliament to the Stolen Generation on behalf of the Australian government.

It was close to 10 years in the making, following the Sorry Book campaign and the first National Sorry Day on May 26, 1998, which was described as “the people’s apology”.

Between 1997 and 1999, states and territories apologised to the Stolen Generations before the federal government followed in 2008.

ULURU STATEMENT FROM THE HEART

In 2015, Indigenous leaders met with then-prime minister Malcolm Turnbull and then-opposition leader Bill Shorten. That meeting resulted in the establishment of the Referendum Council, which held 13 First Nations Regional Dialogues about constitutional reform, to ensure

Indigenous people were at the heart of the reform process.

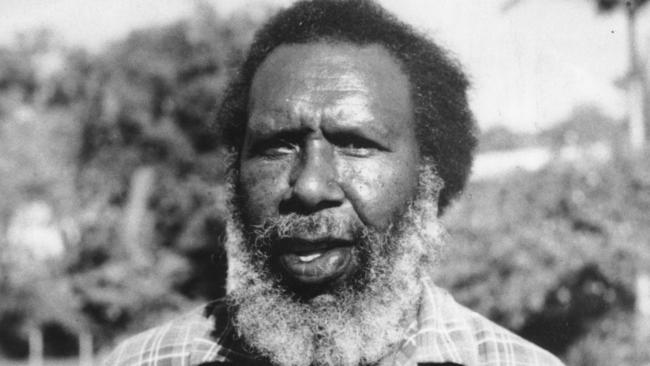

‘TALKING ABOUT OUR CULTURE GIVES ME PRIDE’

Passing on Aboriginal culture and traditions is a point of “pride” for Dharug elder Colin Locke, who has a deep connection with the upper Blue Mountains on the outskirts of Sydney.

As a sixth generation descendant of Yaramundi ‘Chief of the Richmond Tribes’, Uncle Col has ties to the Boorooberongal clan of the Dharug nation.

Yaramundi’s daughter Maria married convict Robert Locke, which was the first wedding between the two cultures, Uncle Col said.

“Next year marks the 200th anniversary of their marriage on January 26,” he said.

Uncle Col, who works with Muru Mittigar to conduct cultural programs, said he loves passing on his knowledge to the next generations and the wider community.

“Our culture was one of the most decimated in Australia (following the First Fleet’s arrival), thanks to efforts from (Lachlan) Macquarie to wipe us out,” he said.

“I feel good talking about it (our culture). It gives me pride and I love taking questions from young kids.”

He works with fellow elder Peter Williams, who at age 25 first started learning about his people’s ceremonies from his uncle, having not grown up with his culture.

“My 11 kids know everything. The stories, dances and songs. (Sharing it) is better than winning the lotto. When I pass, I will die a happy man because my kids know stuff ,” Uncle Peter said.

With a connection to four countries through his family, he takes pride in sharing his culture, not just with Indigenous Australians but the wider community.

“I was told by my uncle, that if you’re born here, you have a right to know the laws of the land,” he said.

Both enjoy passing on aspects of their culture including songs, dances, language, weapons and food.

An example around language is Bondi Beach, which in local language is ‘Bundi’ or ‘Boondi’, named so “because of the sound of the waves crashing on the sand”, Uncle Peter said.

Uncle Col said he had noticed a real shift in people’s interest in Aboriginal history and traditions following the Walk for Reconciliation march across Sydney Harbour Bridge in 2000, that attracted 250,000 people.

HISTORY OF INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIANS

Australia’s First Nations people have 65,000 years’ worth of history in this country. We take a look at some of the main aspects of the world’s oldest living culture and Aboriginal peoples “kinship” with Australia.

FIRST EVIDENCE OF HUMANS IN AUSTRALIA

Australia’s first peoples have been here for tens of thousands of years based on archaeological findings, Australian National University Director of the Research Centre for Deep History Professor Ann McGrath said.

She pointed to University of Queensland archaeologist Associate Professor Chris Clarkson’s 2017 paper on his findings of about 11,000 artefacts at Madejedbebe, in the Kakadu National Park.

“People got here much earlier than we thought, which means of course they must also have left Africa much earlier to have travelled on their long journey through Asia and south-east Asia to Australia,” Assoc Prof Clarkson said at the time.

“It also means the time of overlap with the megafauna, for instance, is much longer than originally thought – maybe as much as 20,000 or 25,000 years. It puts to rest the idea that Aboriginal people wiped out the megafauna very quickly.”

Prof McGrath said Lake Mungo, part of the Willandra Lakes Heritage Site in far west NSW, was also where evidence, dating back 40,000 years, of the earliest human cremation and burial was found.

WHAT DID AUSTRALIA LOOK LIKE WHEN CONVICTS ARRIVED?

It is estimated 750,000 to 1.25 million Aboriginal Australians lived in our country before British settlement started in 1788.

Aboriginal people used their firesticks to change the vegetation of the continent to suit their requirements.

“There were accounts from the ships that around Sydney looked like a park, and we came to understand that as firestick farming. They engineered the landscape to hunt kangaroos and for fire management – the British were amazed by it,” Prof McGrath said.

HOW MANY LANGUAGES ARE THERE AMONG INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIANS?

Languages expert Professor Jane Simpson, of the Australian National University, said there were between 250 and 750 distinct languages or dialects associated with Indigenous Australians.

“Working out how many are still spoken is difficult,” Prof Simpson said.

COMMON BELIEFS, RITUALS AND PRACTICES

Connection to country, spirits and telling stories is important among Indigenous Australians, Prof McGrath said.

“Song and dance, performances, as well as painting and engraving was a really important way to transmit culture and for storytelling. Some paintings were also a map of Country – helping people find the best water or resources,” she said. (NOTE: Country capped on purpose).

“There are songlines, which can travel very long distances. Aboriginal people would be sharing songs, knowledge, trading goods as part of a network. These could be where to get the best resources and how to provide in different seasons.

“Australia has very ancient art all over the country. They knew how to make ochres to make permanent art and used different sacks from trees and traded ochres.”

Indigenous Australians have a “strong respect” and “sense of obligation” to look after the land and waterways, Prof McGrath explained.

“There is a symbiotic sense of health and wellbeing – a close relationship between human life, animals, the hills and mountains. Water is a living force that runs through it. It’s a connection that was broken down through colonisation when people were taken off their land.

“The Country is their own autobiography, the way an individual would see themselves. The word Country does imply belonging.” (NOTE: Country is intentionally capitalised in theses instances).

Originally published as ‘Struggles, triumphs’: Key moments of Indigenous Australians’ history